Last month, in October of 2017, Marsha Hunt began her 101st transit around the sun. She continues to grace our increasingly graceless planet, and while we were always lucky to have her, she seems even more precious now, when we are really in the soup.

Marsha Hunt in 2007, radiant at 90. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Miss Hunt is legendary among serious classic movie fans, but is largely unknown beyond our geeky precincts. Why is that, do you suppose? There are so many reasons that one artist is beloved, even iconic, while another with the same amount of talent and accomplishment is known only to the most devout movie lovers. Why is Bogart the most recognizable star of the classic movie era, while James Cagney, whose career was longer than Bogart’s and equally lustrous, is not equally venerated? Why do fantastic actors like, say, Eleanor Parker or Richard Widmark, who were big stars in their day, now languish in relative obscurity?

The most obvious answer in Miss Hunt’s case is the blacklist. Her career was thriving, and not just in film: In the summer of 1950 she had an offer to host a TV talk show and was starring in a hit on Broadway when she returned from France, where she had dined with Eleanor Roosevelt (they had met in January, 1937, when Hunt, along with Jean Harlow and Robert Taylor, visited the White House). She called her agent to check in, and the offers had dried up. That was it?poof! All gone.

While Marsha Hunt is more than worthy of celebrating for her acting, beauty and impeccable style, it’s bigger than that?that doesn’t get at the unique person she is. Hollywood has always been awash in talent and beauty. It’s the totality of her being and her generous life that are so compelling.

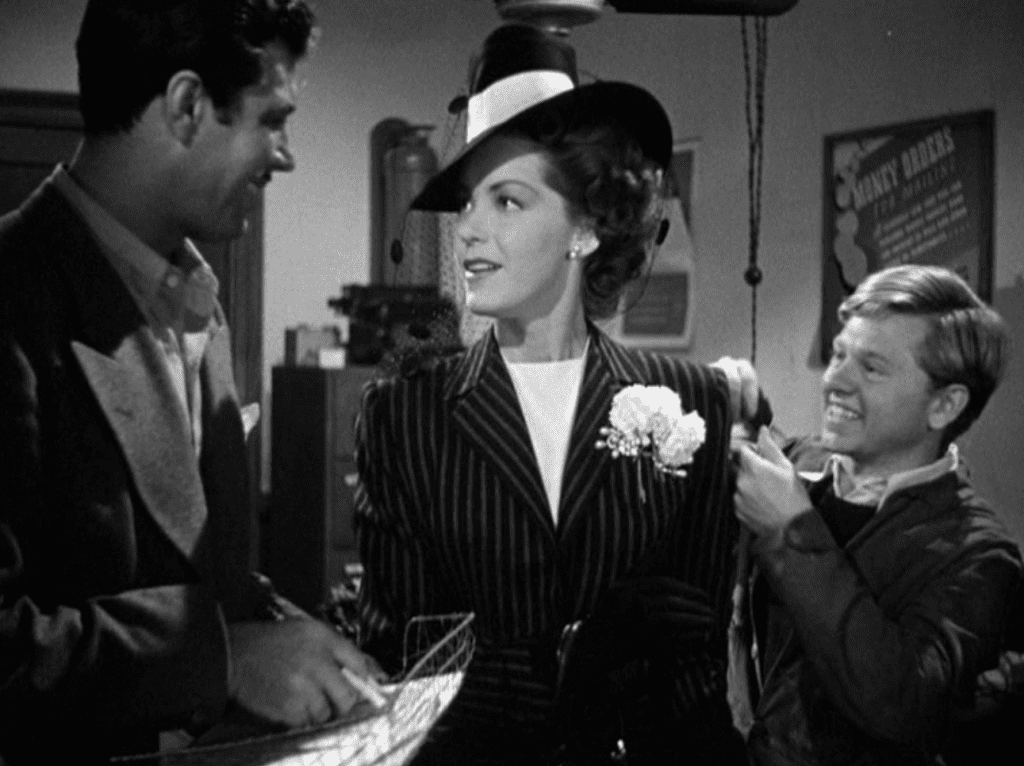

The Human Comedy (1943), here with James Craig and Mickey Rooney.

That life, she acknowledges, has been extremely lucky, and I am inclined to agree with her despite the fact that her career got trampled along with so many others during the Red Scare that began in the late 1940s and spiraled into a crisis that took a sledgehammer to the American values she believed in. McCarthyism stained virtually everything it touched, with a few notable exceptions. Marsha Hunt is one of these. Her?long, beautiful life is a refutation of the industry’s moral collapse under the pressure of the fear and betrayal that roiled America starting about 70 years ago, when she was 30.

All she did was refuse to compromise her ideals to save her career. All she did was let go of what she could not hold onto. After her film work dried up, she and Presnell did some international travel, and Hunt found a new focus. What she saw of hunger and homelessness challenged her to become active with the United Nations, and she became an activist. The commitment to making things better, which had not been gratified in her time at SAG as it sank into political madness, found expression in her new work. And she continued to find ways to help, not just internationally but in her own community of Sherman Oaks, California. She had never been interested in communism, and was not accused of being a member of the Communist Party. But that wasn’t a prerequisite for blacklisting. In that paranoid time, the zealous began demanding loyalty oaths and denunciations, and anything short of a blanket condemnation of communism?not just current or previous Communist Party members but anyone who had ever gone to a meeting or signed a petition that had now come under scrutiny?and loud vows to oppose it to the death were insufficient to clear oneself of suspicion.

Hunt’s great luck includes an excellent gene pool, a happy childhood with loving parents, as well as striking beauty and natural elegance, a keen mind, a good sense of humor, a long, devoted second marriage, and a deep love of and great gift for acting. And that’s not all: her passion for helping others, which found expression in the activism that absorbed her abundant energy when she could no longer work in movies, is a gift to the world. It’s truly an embarrassment of riches, and she has squandered nothing, made the most of everything. It’s no wonder that, at 100, she is still winning new fans and friends.

Hunt’s figure was perfect for fashion?her waist was 22 inches.

In the summer of 1950, Hunt’s name appeared on the infamous Red Channels list of 150 people in broadcasting who supposedly had dangerous political sympathies. Decades later the actor George Murphy, who started his career in politics as the president of the Screen Actors Guild and eventually served as U.S. Senator for California, said that there was no such thing as the blacklist. Murphy had been a passionate commie hunter during the HUAC years. Poison of this sort grows stronger when it’s denied. What did Murphy’s denial even mean, and what was he saying?was he denying his own role in this disastrous chapter in American history?

Miss Hunt does something for hats…

Whispering campaigns by their nature grow in darkness, which makes them difficult to counter?there’s nobody on the record who can be challenged on the facts. In the years after Red Channels, Hunt continued to work on the stage, and eventually she was again able to find sporadic film work, but she had lost the momentum built over 15 years in the business, and there was no way to regain it.

She’s actually better known now than she was 20 years ago thanks to TCM, which shows her films occasionally, as well as to her continuing presence on the classic movie scene, and to strong advocacy by the Film Noir Foundation. Just this past April she turned up unannounced at a TCM Film Festival screening, to the delight of everyone lucky enough to be in the theater. She’s still doing interviews, telling stories about the Hollywood she knew, the blacklist era, and her wonderful, lucky life. I would be thrilled to be as lucid at 60 as she is at 100, but you can’t have everything.

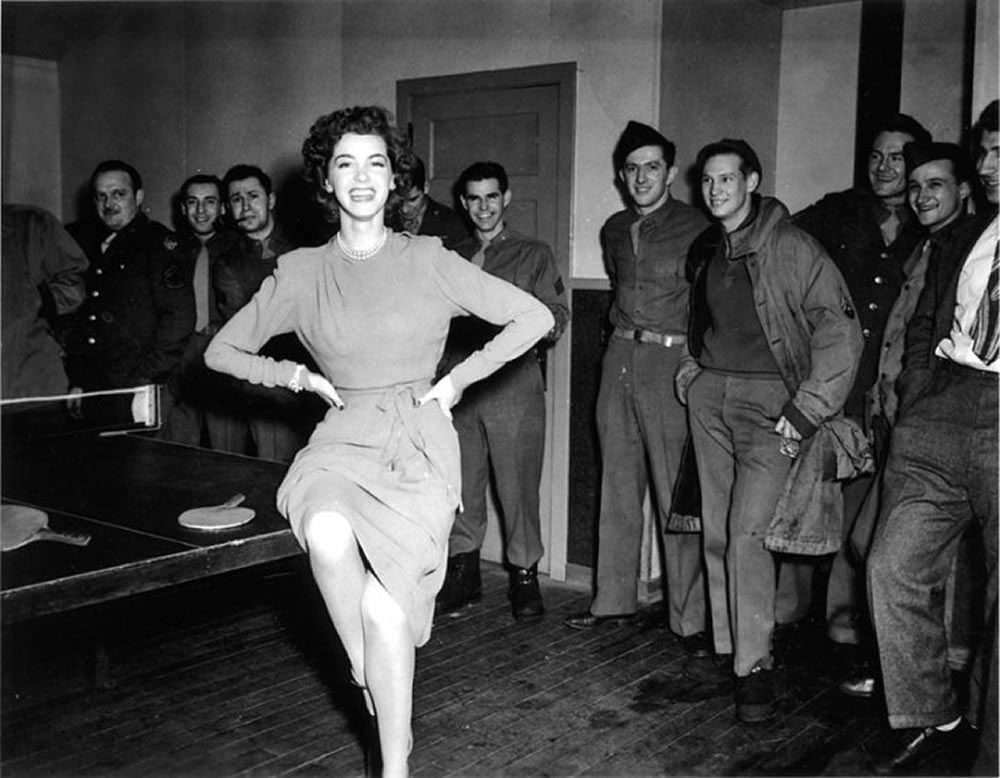

Marsha Hunt entertaining soldiers.

Hunt had made more than 50 movies in 15 years, and while she was not a top star, she was in demand and had appeared in some prestige pictures like Pride and Prejudice (1940), Cry Havoc (1943), and The Human Comedy (1943), as well as a number of less prominent movies well worth discovering, like Kid Glove Killer (1942) and Seven Sweethearts (1942), both with her friend Van Heflin (sigh),??A Letter for Evie (1944), Carnegie Hall (194?), Lost Angel (1943), The Affairs of Martha (1941), and more famously Raw Deal (1947), considered one of the greatest of noirs. In Raw Deal she has the unenviable task of playing the good girl, a particular challenge playing opposite the great Claire Trevor’s vulnerable bad girl. But Hunt makes the good girl believable and attractive. She says, “All I want is a little decency!” And when she witnesses Dennis O’Keefe being savagely beaten by two thugs, she has to make an agonizing choice: Shoot one of them, or watch O’Keefe being murdered. We see her face that conflict, in those few seconds. She shows it all to us without being obvious or looking contrived.

From what I’ve seen, she is never less than excellent. She is a pleasure to watch; her sensitivity to tone and nuance are always evident. As Mary Bennet, the bookish daughter whose inability to hit the high note in “Flow Gently, Sweet Afton” is a running gag in Pride and Prejudice, she spends most of her screen time in the back of group shots, but even there her reactions are perfectly calibrated to add to the sum of the dramatic effect without distracting from the more prominent characters. And her few scenes showcase her flair for comedy. If you know Hunt for other movies it takes a few seconds to register that gawky, geeky Mary is the same impeccably turned out Miss Hunt who was a costume designer’s dream. But Hunt’s ambition was never to be the biggest star, but the very best actress. She took pride in being called “Hollywood’s youngest character actress,” and did her best to live up to it.

Pride and Prejudice (1940): Maureen O’Sullivan, Hunt, Mary Boland

Marsha Hunt had been 17, already a successful New York fashion model with her sights set on becoming an actress, when her film career began in 1935. That’s when Paramount? signed her to a seven-year contract, followed by a long, happy period at MGM in the 1940s that produced most of her best-known work.

in 1947, Hunt and her husband, writer Robert Presnell Jr., didn’t think twice about joining the Committee for the First Amendment in support of the Hollywood Ten, the group of prominent writers and directors who defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities and refused to answer the infamous question “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Today, Dalton Trumbo is the best known of the Ten, but Hunt didn’t know him until decades later when he hired her to play the mother in his film adaptation of his book Johnny Got His Gun. In 1947, Hunt only knew one of the Ten: screenwriter/producer Adrian Scott, who she says is one of the finest people she has ever known. Standing in support of Scott was a no-brainer for Hunt.

Raw Deal (1947)

She recalls, in her interview in Patrick McGilligan’s and Paul Buhle’s Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist, that when she served on the Screen Actors Guild’s board in 1946-47, she was a political innocent. Her father was an extremely conservative Republican, and at first she had been uncertain about even the idea of labor unions because he so disliked them. But her interest and concern in the lives of others was stirred by the meetings, where at first she just listened, but then she began to speak up. She wanted to address the serious issues affecting the membership, including Olivia de Havilland’s suspension by Warner Bros, and stereotyping in casting?not just the very narrow restrictions on the kinds of roles offered to minorities, but how those all-too-rare characters were written. But increasingly, the union’s leadership was focused not on these issues but on what they believed to be the threat of communist infiltration of the industry.

“Flow Gently, Sweet Afton”: Hunt’s dodgy intonation is the movie’s running gag.

Director Sam Wood was among those who in 1944 founded the Motion Picture Alliance [for the Preservation of American Ideals], a single-issue organization dedicated to rooting out supposed industry infiltration by communists. The politically conservative membership included Ayn Rand, Ronald Reagan, Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Taylor, George Murphy, Ward Bond, Walter Brennan, Clarence Brown, Leo McCarey, Irene Dunne, Laraine Day, Dick Powell, and Ginger Rogers, and many of HUAC’s friendly witnesses were drawn from its ranks. These were the people eager to “name names,” though given their political sympathies, the idea that they would know who was batting for the other side seems ridiculous.

Their eagerness to protect America from what they perceived as a real danger was evident, and despite a paucity of evidence regarding communist messages being smuggled into Hollywood movies, the advent of the Cold War provided fertile soil for what it’s now clear was their paranoia. The relationship between HUAC and Hollywood?the studios, the unions, and the Motion Picture Alliance?further confused issues for those accused of being commies. How could you find out who had named you, and how did you fight back? Who did you see to restore your reputation, to regain your position in the industry and community?

Pride and Prejudice (1940): She finally hits that high note when she meets her match.

But that was a few years later. In 1947, nobody could yet see where things were headed. Hunt and Presnell joined other prominent Hollywood liberals like John Huston, William Wyler, Edward G. Robinson, Paul Henreid, Humphrey Bogart, and Lauren Bacall who formed an organization of their own, the Committee for the First Amendment. They only knew that American values, starting with the freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment, were under siege, and they believed that standing in support of the Constitution, as well as their friends and colleagues, was the right thing to do.

The group chartered a plane and flew to Washington in support of the Ten, to attend the HUAC hearings where their testimony had been subpoenaed. Hunt recalls the overnight flight from Los Angeles as cheerful and optimistic, with friendly groups greeting them at the airports they stopped at on the way. Nobody on that flight, and none of the Ten, had any idea what they were about to face. They were about to get their first taste of the ferocity, power, and intractability of the forces arrayed against them, and the mood was altogether different on the flight back home?the contagion of fear had infected them, and their group dissolved soon after.

Marsha Hunt (at front) with the Committee for the First Amendment, on their way to Washington to attend HUAC hearings in 1947. They were confident and optimistic on the way to Washington; the mood was very different on the way home.

Hunt says that they faced immediate hostility, including from the press. Some sources? quoted her as saying things she not only did not but would never say, just as her listing in Red Channels a few years later would list political affiliations she never had. Where did the damning information come from? We will probably never know.

Hunt believes she fell under suspicion from her SAG work, from her attempts to refocus the union on what she saw as its core issues, but more specifically because she contradicted previous SAG president Robert Montgomery’s account of an attempt to merge SAG with the Directors Guild of America and the Screen Writers Guild. He was the venerated insider; she was the earnest newbie who lacked political sophistication. And, though she doesn’t say this, perhaps misogyny also played a part?that is, perhaps her account was discounted before she opened her mouth.

Raw Deal (1947): Director Anthony Mann and cinematographer John Alton shoot Hunt with great delicacy

In any case, after their Washington excursion, those who defended freedom of speech were told they needed to distance themselves from their now-tainted colleagues. Hunt heard that Bogart and Bacall had been called on the carpet at Warner Bros and told in no uncertain terms that their careers were on the line, which shows you how out of whack things already were?usually if you’re making money for the company, they will allow you some leeway in these matters, and Bogart and Bacall were huge stars. But what had been concern over eroding civil rights began to bleed into panic, and Bogart released a statement to square himself with his bosses and the suspicious minds of the Motion Picture Alliance. He was among the first of what would become a flood of artists who would fold under the pressure and compromise their ideals to avoid ruin. It’s hard to overstate the power of seeing the Ten lose everything?not just their power and lucrative careers, but their houses, their marriages. And some of them did prison time. The chilling effect on Hollywood’s liberals permeated everything. Hunt says she waved hi to a friend at the supermarket, and the friend looked away. As she says, it was a cowardly time in Hollywood.

As Victor Navasky writes in Naming Names, his study of the political and ethical disaster that was taking shape:

“The talent blamed their agents, and the agents blamed the studios, and the studios blamed HUAC, and HUAC blamed the pressure groups. The pressure groups blamed their members, said their hands were tied. (However, when the national commander of the American Legion told Martin Gang that the Legion helped to circulate the names of subversives only because their members insisted on it, his fellow attorney Milton Rudin made a tour of Legion posts across the country, only to find that few of the members really cared.) Lawyers blamed their clients, and clients blamed their lawyers. Blacks blamed The Man.

Thirty years after the documented fact, George Murphy asserts that there never was a blacklist. Denial of fact can always be disproved by evidence; not so denial of responsibility.”

?*? ? ?*? ? *

Marsha was lucky again, among the victims of the blacklist: Her husband, bafflingly but fortunately, was not blacklisted, so he continued to work, and they were able to keep their home. While movies, TV, and radio were closed to her, she was able to work in stock and on Broadway. The money was in no way comparable to what she had made in movies?and she says that while she was never among the high earners, she did well enough?but she got to keep doing the work she loved and contributing something to the family coffers.

Raw Deal (1947), with Dennis O’Keefe

In the plague time of the blacklist, panic drove out decency?that word that finally struck at Joseph McCarthy, the Grand Inquisitor, when Joseph Welch spoke for the nation and denounced the great denouncer, saying “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” (And remember Marsha Hunt’s character in Raw Deal saying, “All I want is a little decency!”) Those with a will to power, as they always do, exploited the situation to become judges and executioners as well as fixers who could save you if you’d just follow their instructions and say what they told you to say, denounce who they told you to, condemn your own past, your own ideals, your friends and colleagues.

So there is something particularly surprising and lovely about Marsha Hunt being pretty much the last (wo)man standing from the blacklist era. Miss Hunt somehow evaded the taint. She sold no one out, including herself. She suffered the loss of a career that was developing solidly, and that she loved with all her heart. We lost all the movies she would have made had her life in the movies not been cut off suddenly and irrevocably. It is a serious loss because she was an excellent actress with a unique screen presence and a look all her own, suffused with inner radiance. But in the end it is the radiance that has prevailed. Perhaps Marsha Hunt is still here to remind us that, no matter how dark things may be, in the long run, decency will prevail.

This post was written for the CMBA 2017 fall blogathon. Head on over to see the other entries; you’ll be glad you did…

An inspiring woman and a joy of an actress. You shared Marsha’s story beautifully.

What did [George] Murphy?s denial even mean, and what was he saying?was he denying his own role in this disastrous chapter in American history?

Yes. Yes, he was. Rat bastard.

I recently had the pleasure of revisiting RAW DEAL again for an outside project…and I got a little teary-eyed while watching it, thinking about how people like Murphy and others torpedoed Hunt’s career and then tried to bullshit their way out of it in later years. (I’m also bewildered by how people continue to do so today.)

Thanks for this essay. Very well done.

A lovely and passionate tribute to a lovely and passionate human being. Thanks for telling Marsha Hunt’s story, not just the blacklist years, but the years leading up to and following it. Nice work!

This lady is an inspiration. I was always interested in her, since we share a first name that is not often seen in film stars. Great piece – very well done.

A great tribute to a great lady. I’m glad that she was able to overcome the blacklist and live a long and productive life when so many were destroyed by it.

A great article! Thanks for highlighting her lesser known films. I was in the audience at the TCM film festival where Miss Hunt appeared; I believe it was at a screening of a film with Lee Grant. Such a thrill. We are so fortunate to have her still with us.

Back around the year 2000 I got to interview Marsha Hunt at the Palm Springs Film Noir Festival where Raw Deal had just been screened. I was somewhat nervous since this was my first interview I had done. Marsha made seem like a breeze she was a great interview and an inspiration. Since then I have meet Marsha Hunt at other festivities and she always remembers me. I even had Marsha sign the book she wrote titled “The Way We Wore” its all about the fashions and the clothes she wore in her films its a great book with some beautiful photos.

Wonderful article. Marsha Hunt was indeed a largely unsung treasure — until now! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you kindly, glad you enjoyed it!