Thrilled to be writing this for the 2023 CMBA fall blogathon, because Humoresque is a classic Second Sight movie where the riches it offers mostly get eclipsed. In this case it’s by Crawford’s dazzling diva turn, which sweeps all before it. Hoping to stir you to see it if you haven’t, and if you have but were understandably focused on Joan, inspire you to give it another look.

This is not the full-scale treatment Humoresque deserves, but it’ll give you a taste, and I’ll write the real thing anon.

Humoresque was Crawford’s follow-up to her epic, Oscar-winning comeback in Mildred Pierce the previous year. It would be followed by Possessed, another excellent film, in 1947, to form a three-year run of knockout releases. She looks incredible, stunning, beautifully styled, in gowns by her old fashion guru Adrian, who had costumed her throughout her career at MGM.

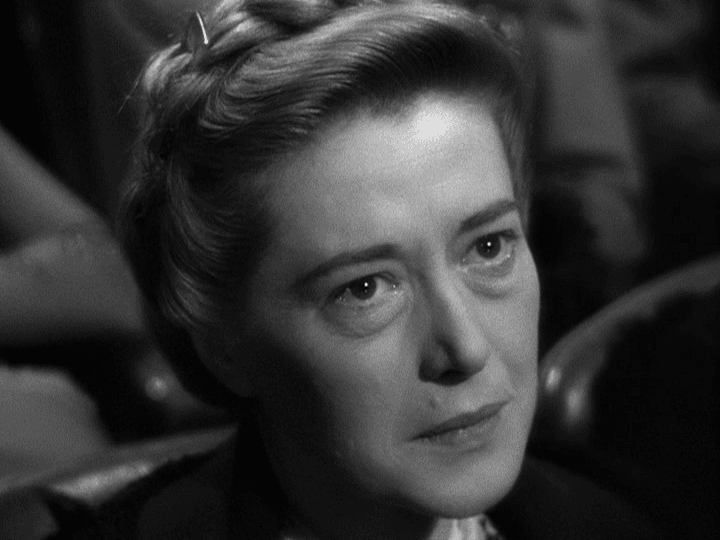

Helen filtering life through a snifter

The role of Helen Wright, the scandalous, tortured society lady who tragically falls for Paul Boray, Garfield’s prickly, self-involved concert violinist, is a perfect fit for Crawford’s strengths as an actress. Helen is all nerves and sharp elbows. She drinks more than anyone I can think of in a movie, in every possible place including the haberdasher where she takes Paul to get him some proper suits—the staff knows her well and apparently keeps bottle, glass, and ice on hand so the poor thing won’t have to survive half an hour without a couple of highballs. Helen is constantly fixing a drink or sipping one or swirling brandy in a snifter. In the rare instances she can’t drink, like at Paul’s concerts, she instead fiddles with her spectacles. Either way, Helen is preoccupied by her glasses, both the kind that blur her thinking, and the others that momentarily sharpen her vision.

Helen’s husband, Victor, is a lost, melancholy guy who loves her but has never been able to “prove his love.” Victor and Helen have a jaw-dropping mansion in Manhattan and a pretty fancy dive down the shore, as the poor people might say. The couple are companions only in their self-involved misery: she disappointed at his weakness, he bearing that shame kind of masochistically. She has several young guys who hover around her, lighting her cigarettes, bringing her her glasses, waiting on her like a queen. She has nothing but scorn for any of them, partly bc I suspect she has only contempt for anyone who is interested in her. Self-loathing saturates her every thought as booze does her every breath.

The women in Paul’s life watching him perform

Helen’s game is to defuse any risk of intimacy by discrediting men she’s attracted to. When Paul plays at one of her parties she is stirred, so she engages in some fairly lame repartee to try to embarrass him, but she doesn’t know him yet: Paul bites back, and she is drawn in though she is terrified, and rightly so, because she has no defense against a total collapse of the shell she has created to stand in for an actual self.

I keep thinking of one of my favorite Joni Mitchell lines: “I’ve been living on nerves and feelings, with a weak and a lazy mind.” Helen is so internally ravaged by something we never learn about (all we get is a couple of lines intended to summarize how she got to be her, but they are her usual glib, not very clever lines, so they don’t tell us much) that she seems to exist only by dulling her wits and pain with booze and by playing a character of her own invention—sophisticated, beautiful, doomed. But she has no other defenses, and when she falls for Paul she is dumped into the ocean of her own wild, unmanageable emotions.

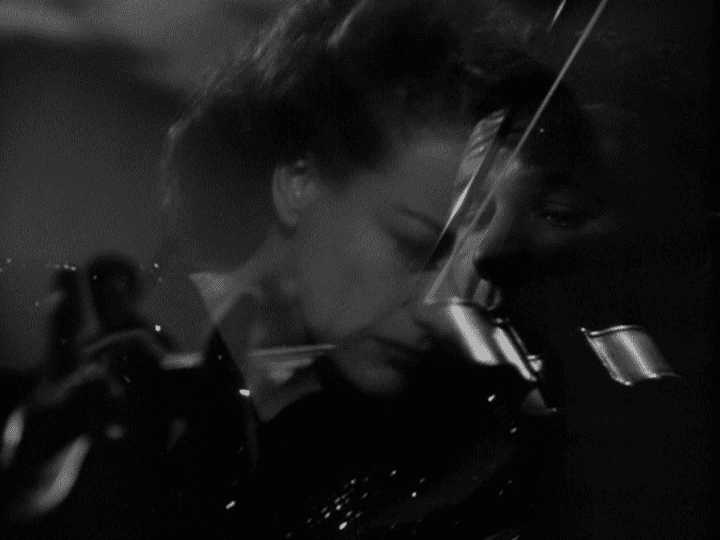

Composer Franz Waxman adapted several classical compositions for violin and orchestra for Garfield’s Paul. The music throughout is thrilling, and the old-school solution to showing nonmusician Garfield playing all that exquisite stuff is so effective that Google has questions like “Does Garfield really play the violin?” Not at all, but no less than Isaac Stern provided Paul’s sound while two violinists’ hands did the fingering in closeup shots of Garfield’s face on the fiddle. It’s amazingly convincing and must have been excruciating to shoot for Garfield and the guys providing the hands, with the former having to show a credible face for a violinist in mid-play and incredibly awkward positions for the real violinists’ hands as they “play” the virtuoso music, fingers flying. If you like classical music and are thrilled at seeing it live, you’ll enjoy this, and there’s quite a bit of it.

You know who gets off on it? The three women in Paul’s life: his mama; Gina, the sweet childhood friend and fellow musician who has always been in love with him; and of course Helen.

Director Jean Negulesco uses Paul’s concerts to show these three women in huge tension with each other, reacting powerfully to his playing. In these scenes Paul is an object of intense attraction, his playing slashing into their deepest feelings of desire and anxiety. We go back and forth between watching him play and the women’s faces, in long takes. In one instance, Gina’s feelings of despair as she listens to Paul play and looks up at Helen, alone in her box, overcome her and she flees the concert hall, running down the New York sidewalk in a downpour as the music thunders, past a row of posters of Paul.

Negulesco was from Romania. He started out as a different kind of artist, a painter. He had an eye for both the emotions that play over his characters’ faces in long closeups and the striking, unexpected shot like that of Gina running. Negulesco had an apprenticeship at Warner Bros. directing short subjects. He made more than a dozen before moving up to features, and he had learned his craft well. He’s perhaps best known for Johnny Belinda (1948), another beautiful movie whose many pleasures tend to be eclipsed by another great performance, in that case by Jane Wyman, who won a Best Actress Oscar for it. He directed a bunch of other movies in a variety of genres from noir to musicals, with great style and verve.

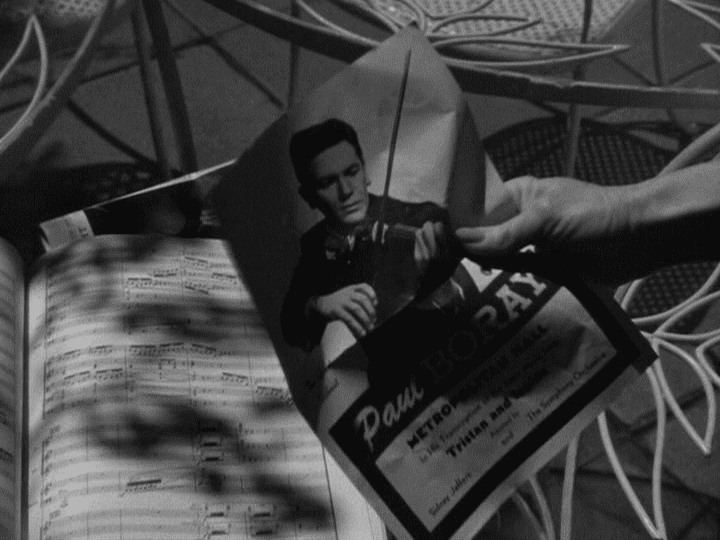

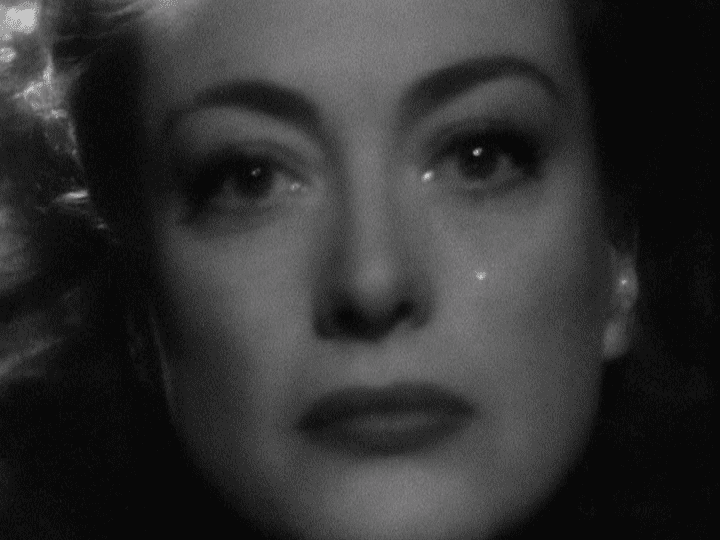

Negulesco’s direction is impressive throughout but he pulls out all the stops for the climactic sequence when Paul’s playing (he’s doing Waxman’s gorgeous adaptation from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, which Bernard Herrmann also used for his extraordinary soundtrack for Vertigo) and Helen’s despair have their final encounter and she walks into the ocean. It’s tough to try to capture verbally the ecstatic quality of her suicide, that is, it’s not like poor old Norman Main in A Star Is Born or any other movie instance of walking into the waves. Helen cannot live with herself, and Paul can’t give up his career for her. Not that that could ever work…Helen in her panic first tries to show him up with her cheap insults, then to turn him into one of her tuxedoed attendants (which comes closest to working; by the end he’s monitoring her drinking and anguishing that she hasn’t showed up to his concert), then by expecting him to interrupt a full orchestra rehearsal to talk to her about their future. Which, of course, he won’t. He is after all a professional.

But just to get one more person to pile on, Helen visits Paul’s mother, whom she knows hates her. Helen makes an odd plea for Mother’s blessing for their planned nuptials, talking with shame of her aimless life, her avoiding life by drinking…she basically hands Mother a loaded gun and begs, “Don’t shoot.” Mom pours salt and lemon juice into Helen’s many wounds, and she is destroyed.

I don’t think Helen planned to walk into the waves, but what’s left for her, really? Her husband is divorcing her, so there goes her social life, and besides drinking and the occasional fling, how can she keep going, now that she understands things can never work out for her and Paul, or for that matter her and anyone else.

The gorgeous, hyper-romantic music of Tristan and Isolde swirls, Helen, totally lost, absurdly totters along the shore in her Adrian gown and heels, somehow hearing Paul’s concert via the radio back at her house, carrying a handbill for the concert. The waves unfurl and engulf, Helen lets go of the handbill, which falls into the wet sand, and as the music reaches its climax Helen, mesmerized, walks into the sea as if she’s been waiting her whole life to lose herself there…

It’s overwhelming—the way Negulesco tells Helen’s last moments, beautiful and aching and utterly mad, as she finally gives in to her desire for oblivion in the vastness of the waters.

. . .

Anyway, first thoughts. More to come, lots more, but this will have to be the first course. Why this movie isn’t better known and more written about I will never understand.

Thank you for coming to my TED talk…now go over and check out the other blog entries, you can thank me later.

You asked why this movie isn’t better known, and while reading your fab review I was asking myself why I hadn’t seen this movie yet, for pete sake. I’ll be watching this very soon, so thank you in advance.

”I’ve been living on nerves and feelings, with a weak and a lazy mind.” Invoked in one incredibly well-written and beautifully descriptive tribute to Jean Negulesco’s film. I’m adding this to the many noirs I’ll be binging this Noirvember. Cheers, Joey

PS: This is Joey from The Last Drive In!

”I’ve been living on nerves and feelings, with a weak and a lazy mind.” Invoked in one incredibly well-written and beautifully descriptive tribute to Jean Negulesco’s film. I’m adding this to the many noirs I’ll be binging this Noirvember. Cheers, Joey

Thank you kindly, Jo, much obliged and a very Happy New Year to you and yours!

My heart did a little happy dance when I saw your subject. I love, love, love this film. For me, it’s a Crawford film way above Mildred Pierce in so many ways. Forget about playing nice ,this is the glamorous woman who screams “movie star.” In many ways it was her great swan song to the golden age glamour, but Joan was always in there swinging ever after. Oh, and Garfield was great, too. Thanks for a great read.

I was first acquainted with this film as a violin student in the early 1980s. My own teacher was a Julliard graduate and since I soaked up their teachings like a sponge, I knew what I was doing on the instrument. But still, the violin playing scenes in this film blew me away and even I believed at first that Garfield might have been a pretty good fiddle player even though something did not seem “quite right” in the sense that his head and neck seemed a bit “disjointed” from what was going on. But it is true that there was very little indeed to give away the magic that goes on literally behind the scenes (or in this case, out of the frame of the camera lens). If real players had to do a double take, you know it was exceptionally well done.

On small “blooper” though to watch for is in the scene where the characters Paul and Sid are playing the last moments of the Mendelssohn violin concerto (with piano accompaniment). This is one of the more ingenious scenes in the movie since there is at first a left rear quarter shot of a real violinist (possibly Stern himself) and then scenes of their fingers on the fingerboard (all legitimate and clearly played by a professional musician).

Then as the end of the piece is reached, the real violinist needs to make a very hasty exit stage right as the camera pans to the left. This is to facilitate the immediate entry into the scene fro the right of John Garfield – obviously dressed identically to the real player who had just exited.

The scene comes off 99% – I still marvel at the ingenuity of it all. It has almost perfect timing in terms of the real player exiting the scene and Garfield seamlessly taking his place (such a scene wouldn’t work in the modern widescreen era). But it falls down in one aspect – the real player cuts the last “E” note short in order to get out of the scene as quickly as possible so as to allow Garfield into the scene as quickly as possible. But the Stern soundtrack really goes to town on the last note – holding onto it for quite a lot longer!

Still, this is a magic film and to this day it remains my favourite film of all time and by a long shot. I just wish it would come out on Bluray with the original source material fully restored and cleaned up. If any film deserves it, it is this one!

By the way, if anyone happens to know where the scenes were shot where the Paul and Gina characters alight from the train after orchestra practice I would love to know. As an Australian I am hopelessly lost in this endeavour but my best guess is perhaps it is near the railway overpass around 70 East 161 St New York. But again, a guess based purely on deduction and looking at contemporary public transport route maps from the era!

thank you for the musical commentary! I lived in New York for 38 years but can’t identify where Paul and Gina disembark from the train, alas.