Why do I watch The Apartment whenever it’s on, and why, after all these viewings, do I get a little bit excited every time it’s on the schedule?

Same reason I watch a lot of movies the same way. I watch them the same way I listen to music I love, which is to say, not to see how it comes out but to enjoy every note, to allow new things and pleasures to reveal themselves as they do with repeated, attentive viewings.

But what is it about The Apartment in particular that places it in this special, very personal category? Like Desk Set (1957), it’s a movie set in a Manhattan office where I might have worked, that reminds me of the work world I became a part of when I moved to the city in 1974. The Chinese restaurant in the movie reminds me specifically of a place called Ho Hos, on the ground floor of the Time-Life Building, where we would go in the middle of our overnight shifts for not-very-good Cantonese food, better drinks, and a chance to collect ourselves and rest our eyes from fluorescent lights and copy.

Also, the mensch thing. One of the few decent human beings in the story is Baxter’s neighbor, Dr. Dreyfuss, who hears the goings on through the walls and thinks Baxter is an “iron man.” He straightens Baxter out, tells him to be a mensch, “a human being,” and wonderfully, Baxter follows Dreyfus’s advice.

Sylvia: Thursday? But that’s The Untouchables, with Bob Stack!

Like all the best movies, there isn’t an unnecessary shot or word. We get many laughs, but we also get a full panoply of emotions, from fear and disgust to hope and in the last few moments, the unexpected catharsis of a happy ending no less satisfying for being not epic but small, personal—all the things the lovers have been denied in the Manhattan skyscraper where they worked and met.

We meet Jeff Sheldrake, head of personnel, serial philanderer and all-around jerk.

The casting is perfect. Initially the villain, Jeff Sheldrake, was going to be played by Paul Douglas, but he died soon before shooting began, and Fred MacMurray came in. Douglas was a good actor, but I can’t imagine the movie working with him as Sheldrake. MacMurray brought exactly the right bland menace for the philandering, sadistic insurance company exec, and the audience was so thoroughly convinced they sent oodles of hate mail, which spooked MacMurray. He swore never to play another bad guy, ushering in his My Three Sons and Disney years. Wilder had started talking to Lemmon about playing C.C. (“Bud”) Baxter while they were making Some Like It Hot (1959), and as far as I know nobody else was even considered for the part. Shirley Maclaine had recently won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Some Came Running (1958), and she is sublime as Fran Kubelik, the unlucky-in-love elevator operator Baxter has a crush on, tortured by her inability to fall for a decent guy. Maclaine’s Fran is a beautiful mess, raw and confused by a game she is trapped in but can’t figure out the rules.

The gaggle of swingers who keep Baxter jumping.

The supporting cast is perfect. A couple of them, the company louses who offer Baxter a chance at corporate success if he just keeps vacating his apartment (and bed) at all hours of the night for their trysts, are a combination of comic elements and plot points, while the tootsies they’re so eager to bed are all comedy.

Miss Olsen, Sheldrake’s secretary, who hears things and passes them on…

The only other important female character from the office is Miss Olsen, Sheldrake’s secretary and one of his ex-tootsies, a virtuoso turn by Edie Adams in cat’s-eye frames. Miss Olsen has suffered watching the women who came after her for four years from her front-row seat just outside Sheldrake’s office, and she’s over it. The plot turns on fed-up Miss Olsen’s actions twice, decisively. First, she tells Fran, recently sucked back into Sheldrake’s lies, trying hard to believe he really is going to get divorced this time, the truth about him. Then, when Sheldrake finds out and fires her, she tells his wife what he’s been doing all these years on those many evenings with “the branch manager from [Kansas City, Seattle, fill in the blank],” and Sheldrake finally gets what he so richly deserves: tossed out on his smug, rotten ear.

Sylvia dancing on the desk for the tipsy mob at the office Christmas party.

But though they’re less important to the plot, I have a special place in my heart for two other tootsies: Sylvia (Joan Shawlee), a company switchboard operator who’s Mr. Kirkeby’s current playmate, and Mrs. MacDougall, the lonesome jockey’s wife who picks up Baxter at a bar on Christmas Eve, when everything changes.

Irrepressible Sylvia is one of nature’s partiers. When her boyfriend is trying to get her out of the apartment she’s still dancing, a little tipsy, pouring herself another martini. When Mr. Kirkeby asks if they can move their date from Friday to Thursday, Sylvia is appalled: “Thursday! But that’s The Untouchables, with Bob Stack!” At the raucous office Christmas party, who’s doing a quasi-strip tease on one of the desks in Baxter’s old department as the crowd of drunken coworkers cheers? Sylvia. You can see why Mr. Kirkeby is seeing her; she’s all fun all the time. She doesn’t seem bothered by being with a married man, or her lack of prospects for a man she might marry. As long as the drinks are cold and the music’s loud, Sylvia is game.

Mrs. MacDougall, Margie to her friends, casts an eye on Baxter, who thought everything was going his way until Miss Kubelik loaned him her cracked mirror…

Mrs. MacDougall is played by Hope Holiday, who I don’t recognize from anything else, but she packs a huge comic punch in her few scenes, mostly from her exquisitely grating voice and gorgeous readings of Wilder’s and I.A.L. Diamond’s very funny dialogue. Margie MacDougall keeps talking about her husband Mickey, the jockey (“He’s so cute, 5’2”, 99 pounds…like a little chihuahua,”), currently locked up in a Havana jail for doping a horse, and how Castro didn’t even answer her letter asking for him to be released for Christmas. She has the bad luck to pin her hopes of a little yuletide ring-a-ding-ding on Baxter, and gets shoved out of the apartment minutes after they arrive. She leaves, but not quietly—screaming that when Mickey gets out, “he’ll push yuh face in, yuh face!”

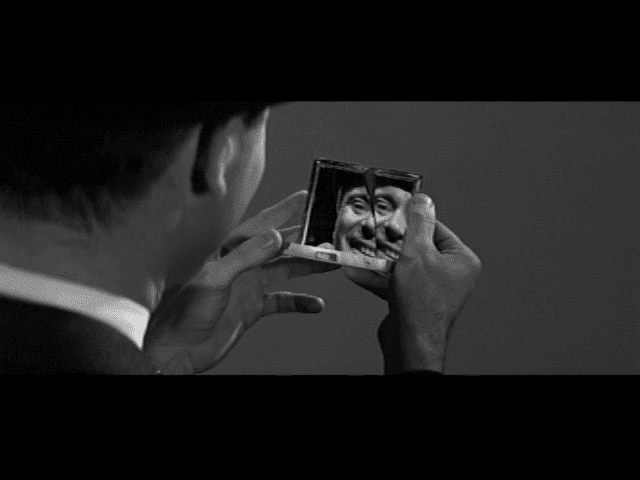

Everything comes crashing down in this one, wordless moment, justly regarded as a stunning bit of screenwriting.

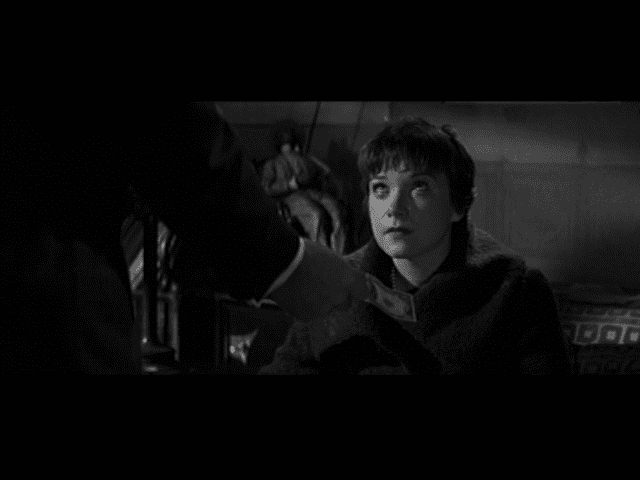

Christmas Eve at the apartment: Fran sees through Sheldrake, no longer able to fool herself about what she means to him.

Just as I’m regretting her exit, Wilder plunges us into the story’s life-or-death events. Baxter and Fran are for the first time thrown together outside the office for a couple of days, and the big shift from painful humor to deadly earnest is smooth as silk. From here until the fabulous ending, the laughs come from some business of Lemmon’s. Nobody else is funny anymore.

Our single glimpse of Mrs. Sheldrake, Christmas morning, as her husband learns what Fran has done and hides it from his better half.

The critic Hollis Alpert, then writing for the Saturday Evening Post, was puzzled by the tone shifts and considered them marks of Wilder’s failure—to him it was neither fish nor fowl, neither a straightforward comedy or drama, and obviously nobody would do that on purpose. Though it was not even a totally novel thing at the time (see To Be or Not to Be (1942), for a prime example) it was about to become coin of the realm, as movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s deeply explored tonal shifts within a single story. Kinda like life itself. But Crowther and his ilk must have been puzzled by the movie’s success—it was the 8th highest grossing picture of 1960, and it won the Trifecta of Academy Awards: Best Script, Best Director, and Best Picture.

Find you someone who will look at you like Baxter looks at Fran…

Wilder was also out front with his subject matter and its treatment. The Production Code was weakening, and other directors, such as Otto Preminger, had been doing their best to tear it down, but Wilder did more than his part. From The Apartment’s first few moments, sex and how we behave around it are central, and treated with a frankness rarely seen up to that time outside pre-Code and noir.

New Year’s Eve at the Chinese restaurant: Fran finds having Sheldrake isn’t the happiness she yearned for. Also, note Joseph LaShelle’s gorgeous cinematography.

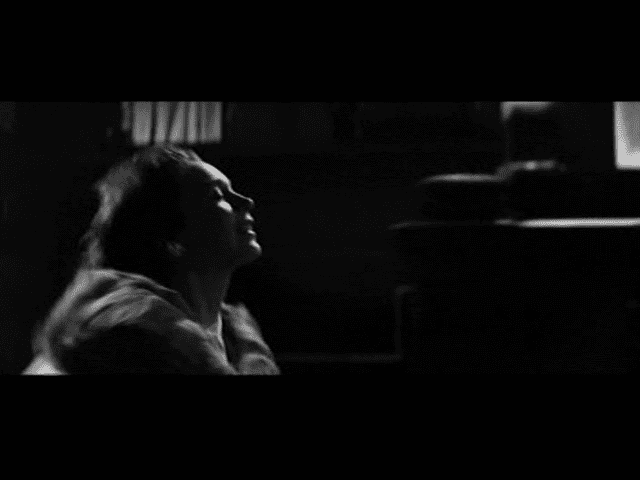

Fran, hearing that Baxter won’t let Sheldrake bring her to the apartment again, and has quit his job, looks happy for the first time in the whole movie.

…and just like that she’s gone, and Sheldrake gets to spend New Year’s Eve alone at the NY Athletic Club. Couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.

A cathartic moment, when the movie’s romantic musical theme finally has a dramatic moment to match: Fran running away from Sheldrake, to the apartment, to Baxter.

I could go on. Actually, I did: This is a totally different essay than I wrote these past few days, and I didn’t even get to how Baxter and Fran are not exactly twins but definitely soul mates, how they’re both being exploited by Sheldrake and the whole corporate culture, Fran for sex, Baxter for a place to have it, both strung along on false promises, and how finding each other under extraordinary circumstances helps them both escape that trap.

Wilder and Diamond follow one of the greatest last lines in any movie from their last picture, Some Like It Hot, with one as good here: “Shut up and deal.”

The Apartment has big themes like power and corporate exploitation and the abominable treatment of women and human beings dehumanized under all that, but it is great because it is about two sweet misfits who ultimately find their own humanity through each other.

This was written for the Umpteenth Blogathon, hosted by CineMava. Head on over and see the other sparkling entries here.

Great review. You highlight everything I love about this film. It must be so difficult in writing a story which has both comedy and drama.

Thank you, Vienna… It must be, it’s so rarely done with this kind of deftness. I have an old poster for it, which sells it as a comedy, how to spin it must have perplexed the marketing department. The writing is hard enough, but then translating those sudden shifts onto the screen seems yet another huge challenge, and it takes real mastery to do that.

Hey, just read your entry, tried to comment but it wouldn’t take for some reason…so here it is:

Hey Vienna, why am I not surprised this is your Umpteenth selection?

Such an interesting movie! I’ve only seen it a couple of times, but to me it brings all of Ray’s emotional intensity to a genre he’s not usually identified with. I feel all kinds of currents washing around, including sexual tension from Emma toward Vienna. And Ray’s use of color here is fantastic. I love Vienna running around in the desert on that red dirt in her white dress, and it remains spotless, glowing white!

To me there’s a fairy tale feeling in this, that shot of Vienna and Johnny escaping under the waterfall…what a fascinating movie, thanks for writing about it.

Oh man, this could have easily been one of my choices for the blogathon (it is forever saved on my DVR). I love everything you wrote and feel it wholeheartedly. I especially love the scene when Baxter looks into the cracked compact mirror. For me, it is one of the most perfect scenes ever filmed. In that one moment we learn and feel so much. Just heaven,

Thank you, Marsha…. the mirror is a moment the master, Lubitsch, would admire the same way Wilder loved him. I would love to know how they came to it. So much information and emotion packed in that little thing, the size of a pack of cigarettes. Just brilliant.

I saw this movie the other year and was very moved by it. I agree with all your praise. It’s funny how the critics weren’t originally keen on it– it amazes me how often the critical intelligentsia wants different, intelligent movies yet doesn’t appreciate them when they walk on by.

Great essay, Leslie! I’m glad you chose The Apartment. It’s one I can see, enjoy and laugh about umpteen times, too. Thanks for highlighting the two “tootsies,’ as their scenes really make the movie. Sylvia’s line about Bob Stack is masterful writing. It shows that Sylvia’s illicit relationship with Kirkeby has reached the point of banal domestic squabbles. The mirror scene always gets me, too, as Baxter instantly and wordlessly comes to realize Fran’s situation. Thanks so much!

Thank you! Excellent point about the banality of Sylvia and Kirkeby’s arguments, too…

Hi Lesley, thank you for joining my blogathon. I look forward to reading your work. You know I admire your writing. You’re going to twist my head right off its spindle I’ll wager.

Lovely comments here for you too. Great!!

Hi Theresa, it was a real pleasure to write about this one, and also to participate in your blogathon, of course! And thank you for your encouragement and positive feedback—a lot of writers aren’t very generous with each other, and it’s something I both appreciate and admire about you…

On my blog, I often mention a phenomena called “revers typecasting.” This applies to we viewers of a certain age who discovered particular actors in order opposite of actual chronology. Fred MacMurray is a classic example (The dad from My Three Sons is a bad guy? What?) But this movie also gives us Mr. Hand from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and Mr. Tate from Bewtiched.

Reverse typecasting—what an excellent term. I’m like you, I first “met” so many stars at the latter stages of their careers, mostly on TV, and MacMurray is a prime example. Those of us who grew up with Baby Jane had the joy of discovering younger Better Davis, ditto with Crawford. Gary Cooper is another whose young self was a revelation to me. And it does require not just changing your idea of what they looked like but their onscreen persona as well.

Just saw this movie for the first time last year, and I can see why people watch it repeatedly. (I’m planning to watch it again myself in the next few weeks.) That scene with the cracked mirror is brilliant.

I love the way you write about film.

Thank you! It’s been a great friend, this movie, and like the rest of the best always rewards repeat viewings.

Yeah, thanks for your thoughts about that FIlM!, which I’ve been watching once or twice a year since decades.

And every time I do I’m going to find some small things, acting-wise or related to the custumes, sets and even the dialog that I haven’t recognised before.

In my opinion Billy Wilder was quite a genius of filmmaking and writing(+ his partners) those scripts.

How he was able to merge or blend in two contrasting themes of life, from brighter lights to the dark ones aka comedy & drama, and almost never got lost in clichés or sterotypes or in typical hollywood-endings, and also creating something like emotionally authentic

stories and settings… and embedded in the art of true-to-life irony, is still a master class that makes cinema special.

To me THE APARTMENT hasn’t dated a bit. Sure soceity & tech-aspects have been changing – but the isolation of caged feeling and haplessness or confusuions concerning all things love didn’t get lesser it rather

has increased.

Also, the writing is so sharp and relevent, still, which makes me rather sad and sometimes even angry when watching so called ‘modern movies’!!! and listening to those lines. Urgh!

Billy Wilder respected the intelligence of the audience, which seems rather obsolete nowadays.

However, thanks again!!!

What a weird looking bed burner (i.e. electric blanket) Bud has!