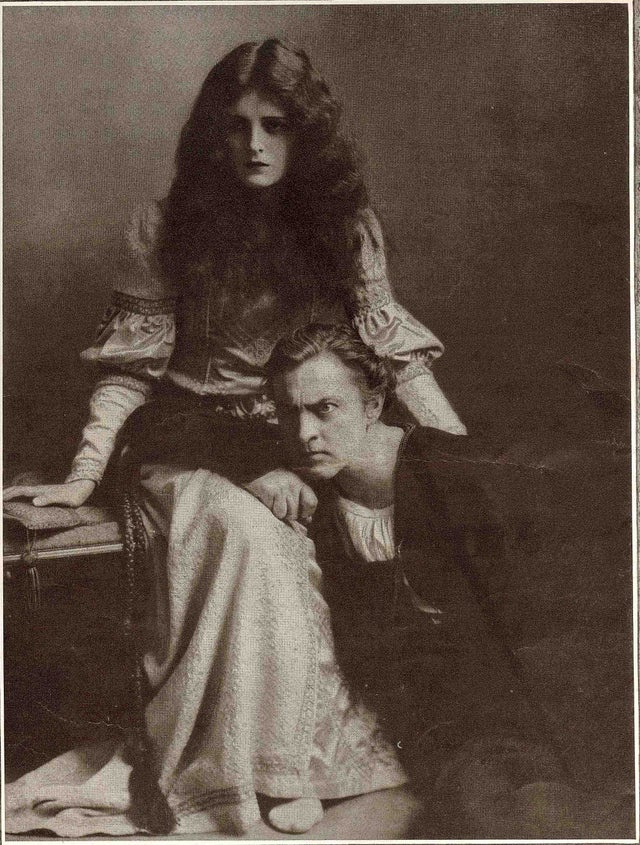

Mary Astor is almost one-stop shopping for a classic film buff. She started working in her teens and was the sole support of her greedy, abusive parents, whom she eventually had to sue for her independence, so she checks that box (see Jackie Coogan, Baby Peggy, Dickie Moore, Judy Garland, and Shirley Temple et al for variations on the Hollywood child star narrative). She began as an ingenue in silents at 15, seeming somehow older than her years, and would soon fall head over heels for her costar and mentorJohn Barrymore, who became both acting coach and lover, so she was an eager participant in a sexual relationship with an older man who had enormous power, so, check. She survived the transition to sound, check. She was definitely part of Hollywood’s film colony, and she worked with everybody, in films from the most prestigious to the programmers the studios churned out to fill their bills, and with directors great and long forgotten, in movies we still watch and those we’d never see if not for TCM.

She had at least a five-act career on film. Act I: silents. Act II: pre-Codes. Act III: the classical era. Act IV: mothers and more mothers, to her great irritation, and at least one memorable, haunting whore, which delighted her. Act V: stage work and television, along with occasional appearances in movies as the studio era limped to a close. And then, perhaps uniquely, a post-Hollywood career as an acutely observant writer of both memoirs and novels.

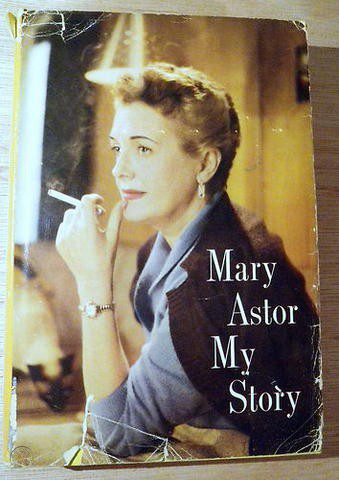

Her two memoirs, My Story (1959) and My Life On Film (1971), together present a full self-portrait, the first of her personal life, the second of her experiences and reflections on acting as well as her observations from her four decades in Hollywood movies, more than 100 between the mid 1920s and the mid 1960s, spanning the silent era, the pre-Code era, the golden age, and the decline of the studio system.

She calls My Story a “biographical analysis,” a nod to a book written as a spiritual task of self-examination, assigned by the priest/psychiatrist she was working with. It indicates the seriousness she brought to the project, just as she did to her acting, no matter if it was a major film with a top-notch director or a piece of B movie fluff. This was not to be a justification, a rosy work of self-promotion, a gloss to sanitize her messy life, which included abuse, scandal, alcoholism, suicide attempts—written from a place of relative serenity. That said, she surely recognized that even the most rigorous biographical analysis she could manage was a commercial enterprise, that she needed to attract readers, so she is not unsympathetic to her editor’s directions to play up the sex and drinking. Right around the same time, I’ll Cry Tomorrow and My Wicked, Wicked Ways were all over the bestseller lists, so it seemed to be what the public wanted.

She calls My Story a “biographical analysis,” a nod to a book written as a spiritual task of self-examination, assigned by the priest/psychiatrist she was working with. It indicates the seriousness she brought to the project, just as she did to her acting, no matter if it was a major film with a top-notch director or a piece of B movie fluff. This was not to be a justification, a rosy work of self-promotion, a gloss to sanitize her messy life, which included abuse, scandal, alcoholism, suicide attempts—written from a place of relative serenity. That said, she surely recognized that even the most rigorous biographical analysis she could manage was a commercial enterprise, that she needed to attract readers, so she is not unsympathetic to her editor’s directions to play up the sex and drinking. Right around the same time, I’ll Cry Tomorrow and My Wicked, Wicked Ways were all over the bestseller lists, so it seemed to be what the public wanted.

But how do civilians and casual classic movie fans know her? For a real pip of a scandal, compelling that at least two books have been published about it in the past five years, a scandal that threatened to take her daughter from her and wreck her career, but she survived, as she did so many other blows. There’s no need to get into it here, but if you want to know more, google Astor and “the purple diary” or “1936 custody battle.” You’ll find plenty. She had been tabloid and fan magazine fodder for well over a decade at that point, and it was the writers of these who controlled the story. It would be more than two decades before she could claim that power for herself.

Of her more than a hundred appearances on film, she is definitely best remembered as Brigid O’Shaugnessy, the serial killer femme fatale in The Maltese Falcon (1941), a magnificent performance worthy of its fame, very much worth watching closely. But she’s also fondly remembered as the mother in Meet Me in St. Louis, and in Little Women, and it is a measure of her acting skill and professionalism that we get not a single clue while watching her that she hated making both these beloved movies.

She won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her portrayal of Sandra Kovak, the flamboyant, narcissistic concert pianist who wreaks havoc with the love life of her rival, a saintly, unusually subdued Bette Davis, in The Great Lie (1941). Davis wanted Astor for the role partly because she had seen Astor play the piano (she had played since childhood, taught by her despotic father), and she generously gave Astor plenty of room to stretch out and play big. The two were unsatisfied with the script and reworked some of it themselves. The experience was a high point in Astor’s long career, and she and Davis became good friends.

Astor’s writing is incredibly clear and vivid. She was an incessant reader with a sharp intellect, and in both memoirs we get the benefit of it as she describes her adventures (and often her boredom) in the movie business, and the people she encountered in it. This would have made for two exceptionally entertaining volumes, but it is her unsparing honesty about her own failings and flaws, rendered with some compassion, that really sets her memoirs apart. The interplay between her personal and professional life is always fascinating.

Her romance with Barrymore embodies the cross currents between the forces she was struggling to manage, as a young girl does, with no sense of her own power. Her parents’ obsessive control over every aspect of her life—she is not even allowed to close the door to her bedroom; her rising pay all went to her father, and after losing Barrymore at 19 she had to negotiate hard, when she was earning $2,500 a week ($37,000 in today’s dollars), for a $5 allowance—had disabled her. He encouraged her to stand up to them, to make the moves she knew would make her a better actress and enhance her career, and watched with increasing dismay as she failed to make the break. Looking back, she sees when he began to drift, and recalls the sickening realization that he had fallen in love with the beautiful Dolores Costello, best known to most of us from The Magnificent Ambersons, playing a woman whose failure to stand up to her tyrannical son not only guarantees her losing the only man she’s ever loved, but kills her.

And yet Astor sees in retrospect that with her parents, all the power was hers, if only she had been able to claim it: she was the golden goose, she made all the money. But she was hobbled by more than the naivete of youth. For her entire life she had been trained by abuse and control over every aspect of her life, and while friends and a despairing Barrymore had told her in no uncertain terms that she had to break away, to claim her life and independence, her parents’ tyranny had succeeded brilliantly in breaking her connection to herself. And that it was this broken link that would keep her from standing on her own, from even having a sense of a self, until—finally, years after both parents were dead and her heyday as an actress had come and gone—she found her freedom, power, and some measure of peace in the process of writing and a newly found Catholic faith.

There were agonizing losses, first Barrymore, who grew tired of waiting for her to assert herself and break free of her parents, and only a few years later the death of her first husband, Kenneth Hawks (brother of Howard), in a midair plane crash during preproduction for a film he was to direct. She had been trying to settle into married life with a man she loved who was, she writes in My Story, undersexed. But she describes some real happiness in this brief marriage, her first attempt at independence. She describes her parents bursting into the theater where she was performing just after she had heard the news, and predictably carrying on about how badly *they* felt, showing not a shred of concern for her shock and devastation. They wanted her to come home with them, to be their “little girl” again. She was not having it, she was resolved to never again enter the home she had shared with Hawks, or her parents’ home (which she had bought for them), either. A few years later she appeared in The Lost Squadron (1932), as a movie star trapped in an abusive marriage to Erich von Stroheim. The picture was about flying, a small group of pilots who had been aviation pioneers in World War I but couldn’t find work upon returning home and ended up flying incredibly dangerous stunts in Hollywood. I cannot imagine the trauma of working on this movie after her shocking loss.

There are endless resonances and rhymes between Astor’s real and reel lives. She felt trapped in all those mother roles she played so well, and perhaps she would have felt this even with a different personal history. But there she is, as Marmee and the stable, well-adjusted mother in Meet Me in St. Louis, strong and giving, properly focused on her children, the mother she herself needed so desperately but did not have.

It’s not at all surprising that Astor’s alienation and profound damage led her to alcohol, or to ill-advised romances, either. We do what we have to to survive, even if it kills us. But Mary Astor was a survivor, and her discovery of herself as a writer brought her a joy and confidence her acting work only did intermittently.

So she leaves us not just a large catalog of movies, from the sublime to the ridiculous (she’s always excellent, though, no matter how slight the movie), but these two extraordinary memoirs. Neither is in print at the moment, and used copies have become scarce and insanely expensive. But keep a look out, someone may reissue them one of these days, and if you can find an affordable copy, it will be well worth it.

She dedicates My Story to her parents: “For my mother and father with love because I understand them now.”

Here’s some more Astor, writing and video, if your interest is piqued:

link to Farran Nehme’s 2010 piece, an interview with Astor’s daughter Marylyn, the subject of the 1936 custody battle and diary scandal:

http://selfstyledsiren.blogspot.com/2010/07/you-dont-wanna-know-about-how-frank-she.html

“More Mary and Marylyn,” a follow-up:

http://selfstyledsiren.blogspot.com/search/label/Mary%20Astor

Greenbriar Picture Shows blog, Pt. 1 (linked by Farran in 2008), from 11/6/2006:

https://greenbriarpictureshows.blogspot.com/2006/11/monday-glamour-starter-mary-astor-part.html

YouTube interview clip, she talks about Fairbanks, Sr.:

https://youtu.be/QlnJEsB3tH4

Mary as Norma Desmond in 1956, TV production, with Darren McGavin as Joe Gillis:

https://youtu.be/sqqGiyMcNVs

Brief newsreel clip of Astor and the other winners at the 1941 Academy Awards:

https://youtu.be/4tOZ-IU7izg

Astor films worth seeking out:

The World Changes (1933)

Other Men’s Women (1931)

The Little Giant (1933)

Red Dust (1932)

Dodsworth (1936)

The Hurricane (1937)

The Prisoner of Zenda (1937)

Midnight (1939)

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

The Palm Beach Story (1942)

Act of Violence (1949)

The Great Lie (1941)

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

Blonde Fever (1944)

Claudia and David (1946)

A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

Return to Peyton Place (1961)

Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte (1964)

This was written for the 2020 edition of the What a Character blogathon, cohosted by Aurora, Paula, and Kellee. Do yourself a favor and check out the other entries here…

Thanks for sharing the Astor links. I was looking at “A Life on Film” on amazon a few weeks ago, and am kicking myself now that I never ordered it.

I loved your analysis, and I always love your writing. Thanks for sharing your research with us.

Great article, Lesley! I would like to add Desert Fury to your list of suggested viewing….Astor plays Fritzi, a fast-talking, chain-smoking casino owner who has an interesting fixation on her daughter, played by Lisbeth Scott. Astor steals the film, she is glorious!

Thanks, Susan, added to the list. I think TCM shows it once in a while but my interactive guide never shows Astor, so I didn’t know. Will keep on the lookout…

Mary, as you deftly point out, truly was the comprehensive Hollywood actor experience. I have enjoyed her many roles and wish I could see more of her silents and read her books. Thank you for your wonderful contribution!!

Thank you, Kellee, for hosting the blogathon again!

I’m so glad to see her getting her due, finally, instead of her work getting mostly shrugged off so people can get back to scandals.

A Life on Film was my introduction to Mary’s writing. I borrowed from the library and waited for ages for it to hit the discard bin!

Your article was a complete pleasure to read; so full of understanding alongside the information. Thanks as well for those links, because certainly our curiosity is piqued.

My Story and A Life on Film are both on my book shelf, two of the best autobiographical books on/by classic era actors out there. That her career included working with both John Barrymore and James Dean is probably unparalleled. Such a beauty she was, but also very talented. I’m thinking of her comic turn in The Preston Sturges film The Palm Beach Story, her femme fatale in The Maltese Falcon and worn-out and weary Jewel Mayhew in Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte. Love her.

Saw Palm Beach Story in the Chinese Theatre at TCMFF a few years ago, and a few members of Astor’s family were there. I LOVE her in that role and was sorry to learn that she had a terrible time making it, and it was not a movie she liked at all. Oh well, that’s a real pro—you can’t catch her working, she seems to be having a swell time.

You probably know, but there’s a new Astor bio—The Great Lie: The Creation of Mary Astor, by Kathleen Spaltro. Seems like it has a similar perspective to mine in this piece, and about time! So tired of the tsk-tsk approach that buries the subject in their hard luck or worst breaks or even self-destruction. People like Buster Keaton and Mary Astor are diminished in stature when we let them set in patronizing pity instead of celebrating their resilience and the incredible work they left as legacy.

Years ago I had the chance to buy a copy of Mary’s novel The Image of Kate, and it was a great read. Mary was a talented actress and a wonderful writer. I haven’t read her autobiographies, but I hope I have a chance to read them someday. I loved your tribute to Mary.

Kisses!

Thank you kindly, Le! Kisses to you as well… <3

And I hope both her memoirs get reissued one of these days, you will love them!

I think that you are also a wonderful writer.

Thank you so much, I appreciate that.