As Stanwyck’s shipboard cardsharp “father” in All About Eve (1942)

He’s one of the preeminent character actors of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and, like Sydney Greenstreet and Marie Dressler, among the small club of performers who started hugely successful movie careers around age 60, which at the time was not “the new 50,” it was less Golden Age than Golden Years—time to sit on your laurels and yell “Hey, kids, get off my lawn!” Instead, having only months before lost Ivah, his beloved wife and professional partner of 31 years, Coburn got on a train to Hollywood for a one-picture deal at Metro and immediately became as indispensable to the movies as he had been to the American stage for nearly four decades.

I’m as fascinated by the latecomers as I am by the Rooneys, Garlands, and Dickie Moores who started their screen careers when they were barely out of diapers. I love to watch people grow up and find their voices, see how they chart their uncertain course in the business and in their personal lives. But those who come late to the party, fully formed and with full lives already behind them, are equally intriguing. What’s the story they carry in their voices and faces, where did they come from, what did life throw at them along the way, and how did they respond? What did life make of them, and what did they make of life?

In Coburn’s case, he was prominent enough that I figured there’d be a full-length biography, or if I got luckier, even a memoir.

I didn’t get lucky.

So after the obligatory stops at his Wiki and his entry in David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film, I started nosing around for other blog posts. I read just one—Cliff Aliperti’s at his Immortal Ephemera site, mainly looking for clues and sources—and started poking around for online links.

This kind of research always puts me in mind of Citizen Kane, and I indulge in an entirely unearned identification with the nameless reporter character who spends the better part of a week trying to plumb the mystery of identity before wanly saying No, he hadn’t found out what Rosebud was, but in any case it wouldn’t have revealed who Kane really was—it was just a piece in a jigsaw puzzle.

Some of you know what this is like. You find contradictions and errors, or intriguing little factoids that raise way more questions than they answer.

With Coburn, this begins at the beginning, with his birth. Some bios say he was born in Savannah, Georgia, but it was actually, per Coburn himself, Macon, Georgia, in 1877, and it was a few years after that his family moved to Savannah. So Coburn was born in the heart of the Confederacy, where veterans of the war would have been everywhere and as Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Do the place and era of his birth explain the fact that Coburn was supposedly a member of White Citizens’ Councils, white supremacist groups? He was a proud son of Georgia who left his papers to the University of Georgia. I ran across one reference to his railing against the 14th Amendment in a late-life interview. It is painful to confront things like this about a beloved actor, someone you feel as if you know. But of course, you don’t, and people are complicated.

All accounts say he began his theatrical career at the Savannah Theatre as a program boy, though he said he was 13 and other sources say 14—I’m inclined to go with his own recollection, though one can’t ever be sure the source isn’t exaggerating for effect….

But all sources including the primary one, our boy Charles, agree that having risen through all available jobs at the theater, when he was 18, he became the Savannah’s manager. This would make it 1895.

I found no references to his parents or the circumstances of his upbringing. Was he at the theater out of love, or did his family need the money? I’m thinking here of Claude Rains, who began his work in the theater at the age of 10, his childhood one of grinding poverty. But of Coburn, at least with what I found poking around online, we have to speculate or leave it alone.

Rich, pervy Uncle Stanley, In This Our Life (1942)

In 1901, he moved to New York. That leaves six years between 18 and 24 for him to practice his trade and prepare to take on the big time. He says he originally hoped to become a “light opera comedian,” but when he saw a Shakespeare play, he was lost, or maybe found. The classics would always be the foundation of his passion for theatre.

What was that New York like? Now I’m thinking of Marie Dressler in Dinner at Eight, her eyes misting with nostalgia as she recalls the New York of her greatest years, when she was the toast of the town, young, beautiful, talented, successful, and surrounded by adoring swains. She pictures snow, and carriage rides to Delmonico’s. Dressler could probably have drawn on her own memory for that moment. Coburn’s turn-of-the-century New York was probably a bit less misty, but it’s always a good idea to have one’s salad days in one’s youth, when one is strong and has a high tolerance for squalor.

But look, by 1905 he starts his own company, the Coburn Players, and meets Ivah. They marry in 1906 and until her death in 1937, they are partners in life and work. Supposedly they had six children. Supposedly one of them became an auto mechanic who married a teacher, moved to California, and fathered movie star James Coburn. Is this true? I do not know.

I found that Playbill has a terrific site with a database of old programs, and while it doesn’t list all of the 30-something Broadway shows in which Coburn was actor, director, producer, or all of the above, it did provide a bit of background for this largely ignored part of his career. Here’s Coburn’s bio from WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST of Around the Corner (1936); according to Playbill, it ran for only 16 performances:

WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST

CHARLES COBURN (Fred Perkins), one of America’s foremost actor-managers, was honored last June by Union College with the degree of Master of Letters in recognition of his services to the American theater. Having embarked to the “enchanted aisles,” that marital and professional partnership known as Mr. and Mrs. Coburn entered upon a lifelong devotion to the classics and other nobilities of the theatre, with a repertoire eventually accruing of sixteen plays of Shakespeare, one of Moliére, three from the Greek and more than a score of the Old English, early American and moderns. They have played under the auspices of a hundred colleges and universities and once—the only actors ever invited to do so—they gave an evening performance on the White House grounds. Some of Mr. Coburn’s most important New York appearances have been in “The Better ‘Ole,” “The Yellowjacket,” “The Imaginary Invalid,” “So This Is London,” “The Farmer’s Wife,” “French Leave,” “The Bronx Express,” “Old Bill, M.P.,” “Falstaff,” “The Plutocrat” and “Lysistrata.” Mr. Coburn was in the all-star casts of “Diplomacy,” “Peter Ibbetson,” “Trelawney of the Wells,” and The Players’ production of “Troilus and Cressida.” He was Father Quartermaine in “The First Legion.” Last season he was starred with William H. Gillette, and James Kirkwood in the revival of “Three Wise Fools,” and last June he played the title role in The Players’ revival of George Ade’s comedy, “The County Chairman.” Ol’ Bill, Falstaff, Macbeth, President of the Senate of Athens, Bob Acres, Rip Van Winkle, Col. Ibbetson, and Henry VIII are among the fine portraitures in his gallery of stage characters. At the invitation of President Dixon Ryan Fox of Union College, Schenectady, the Coburns have been importantly engaged during the past two summers in organizing and directing at that college The Mohawk Drama Festival and the separate but related enterprise, The Institute of the Theatre. The central feature of the Summer Session is a festival of great drama, presented by a distinguished professional company, now established as an annual event of national significance taking on a character similar to that of the Stratford and Malvern festivals in England. /

The Coburns were part of the top echelon of the New York theater scene. For the 31 years of their marriage, they moved in those circles. I found this 1942 New York Times piece on Coburn, which has some wonderful color and detail about his life, where he lived, his sense of humor.

“Piggy,” Lorelei Lee’s dishonorably intentioned diamond mine owning friend in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

NYT, 1/18/42, p162, by Theodore Strauss

via TimesMachine

A Man and His Monocle

Charles Coburn, Traditionalist, Keeps Step in a Changing (Show) World

Charles Coburn is 63, a fact which alone gives him the right to appear in public with a monocle. Happily he also has the rather special sort of face a monocle requires, a certain paternal austerity, a benign aloofness—in short, the countenance of a man well fed upon a rich tradition. If the man is also of a height ordinarily reached by other men only on stepladders, that helps greatly too. Most of all, however, it is the tradition that counts, and in Mr. Coburn’s case he has aplenty. He has been a pillar in our theatre for longer than most of us can remember, and if latterly he has made a pretty farthing by displaying his talents in the West Coast Shangri-La in such items as the forthcoming “King’s Row,” it is a tribute to his culture and attainments that Hollywood is the place where he works contentedly eight months a year. New York is where he lives.

It is understandable, of course. Mr. Coburn was nurtured in a mellower climate than that which made Sammy run. Though by no means an old fogy to sit in slippered state at The Players, his mind is solidly furnished; it has the bright polish of old brasswork. It is stocked with reminiscences of those years before the theatre became prohibitively expensive and movies alarmingly cheap, and it is strewn as full of Shakespearean quotations as a brook with pebbles. Over the years his mind has obviously assumed a sort of protective coloration that blends well with the comfortably old-fashioned furnishings of the lofty-ceilinged studio salon near Gramercy Square.

Charles Coburn, Esq.

Mr. Coburn first moved into the premises in 1919 when Bohemia still stood on a bearskin and daubed pigment on six-foot easels. Somberly paneled, and with a fireplace large enough to roast a fair-sized midget, the room itself is a veritable museum of carved mahogany, portrait paintings, and assorted abracadabra. Most of the furnishings, Mr. Coburn explains, are props accumulated from that long line of plays in which he and Mrs. Coburn appeared and often produced, from their marriage in 1906 until her death several years ago.

“I couldn’t sell the stuff for a nickel,” he confides gently. “But it’s a kind of reminder. It reflects the lives of a couple of people who lived here for quite a long time.”

Like an elder craftsman who can wear the toga with authority, Mr. Coburn is apt to become troubled over the future of the art of acting. America, he says, has not produced an outstanding actor since 1926. Personalities, yes, and glamour boys and girls, but not an actor who can play a gentleman one night and a guttersnipe the next with equal effect. The old stock companies, where a young actor could spend his apprenticeship among experienced performers, are gone, and the colleges, where acting could be taught in concert with more mature talents, have thus far failed. The result, Mr. Coburn gloomily believes, is an art dying in the hands of those who could still pass it on.

Cycles and Bicycles

Mr. Coburn himself began early. At 13, he took a job as program boy in the Savannah Theatre and five years later became its manager, the youngest entrepreneur in the country. During the two years under his aegis he saw such stars as Henry Irving, Ellen Terry, Maxine Elliott, Mrs. Fiske, Modjeska, Otis Skinner, Richard Masterfield and Stuart Robson walk across his stage. Meanwhile he in turn was preparing for a career as a light opera comedian in amateur productions of “The Mikado,” or “The Little Tycoon,” and he still remembers the lingering glow of that night when Emma Abbott, a reigning favorite, snatched him from a crowd of enthusiasts and kissed him roundly. Ever since, he has been “flattered beyond words” by requests for autographs—thinking that perhaps some youngster may feel as he did. “That is as it should be,” he says, falling into quotation. “It is a world of make believe, and it is in ourselves that we are thus and so.”

In later years, and before his long association with Mrs. Coburn as an actor-manager, he spent his apprenticeship as utility man, advance agent, and once, as a means of making a living while looking for work in New York, as a member of the “greatest bicycle racing team of all time.” But when that career threatened to take him from his Broadway precincts, he pawned his bicycle for $29 and hasn’t been on a wheel since. In fact, Mr. Coburn no longer cares for healthy exertion as its own reward.

“Look at all those people who exercise regularly,” he exclaims. “What happens to them? They die!”

Listen to that—he sounds just like Charles Coburn!

And then in December, 1937, Ivah died, leaving Coburn bereft of his companion, his wife, his theatrical partner. But a man of such energies, an entrepreneur who had acted, directed, produced, and run his own touring company for decades, was not ready to fade away from grief at 60. Ten months later, in October, 1938, he got on a train and headed out west to begin his next act, the one we know him from.

NY Times, 10/10/37, no byline

CHARLES D. COBURN TO APPEAR IN FILM

Stage Actor Leaves for Coast for Role in “Benefits Forgot,” His First Motion Picture

Charles D. Coburn, stage actor, the director of the Mohawk Drama Festival at Union College, Schenectady, NY, left by train for Hollywood yesterday afternoon to appear in what was said to be his first motion picture.* He is to play in “Benefits Forgot,” a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production, in which Walter Huston will be starred.

J. Robert Rubin, vice president and general counsel for M-G-M, said that Mr. Coburn had been signed to a one-picture contract with an option on his future services. Production work on “Benefits Forgot” will start next week, he said.

As director of the Mohawk Drama Festival, held every summer at Union College, Mr. Coburn has repeatedly voiced the belief that there is now a “crisis in the American theatre” because there were no stock companies to serve as a training school for young players.

Mr. Coburn appeared on Broadway in March in “Sun Kissed” and in 1936 played with the late William Gillette in “Three Wise Fools.” For many years Mr. Coburn appeared on the stage with his wife, the former Ivah Wills, who died last December 27.

A few months later, he’s comfortably ensconced in his Hollywood Blvd apartment, throwing a reunion for cast members of a popular show he had been in 30 years before. I’ve boldfaced names you’ll probably recognize…

NYT, 1/3/39,

“Old Bill” Holds Reunion

Coburn is New Year’s Host on Coast to ‘Better ‘Ole” Actors

Special to the New York Times

Hollywood, Calif., January 2—Survivors of “The Better ‘Ole’” company made New Year’s the occasion of their first reunion in twenty years as guests of Charles Coburn, the original Old Bill, at his apartment here.

Stage and film celebrities turned out to greet him and the others comprising “three muskrats,” Charles McNaughton, Bert, and Collin Campbell, Alf.

Others of the old troupe present were Mrs. Kenyon Bishop, the original Maggie; Lynn Starling, who played the French colonel; Eugene Borden, the French porter, and, collaterally, F.H. (Frankie) Day the Gramercy Park greeter of the dawn who played with Mr. Coburn in the sequel play, “Old Bill M.P.”

The “muskrats,” the Tommies created by the wartime crayon of Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, donned white aprons in their post-war “pub” and served guests, who included several members of The Players in New York and many once associated with one of the five companies that played “The Better ‘Ole” on Broadway and on the road.

Among them were Mr. and Mrs. Guy Kibbee, Mr. and Mrs. Monte Blue, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth MacKenna, Mr. and Mrs. Patterson McNutt, Walter Connolly, Nedda Harrigan, Mr. and Mrs.Charles Judels, Pedro de Cordoba, Fritz Leiber, P.J. Kelly, Thomas Mitchell, Andre Charlot, Janet Beecher, Olive Wyndam, Marcella Burke, Georgia Caine, Emma Dunn, Marjorie Wood, Frieda Inescourt, Esther Dale and Irene Rich.

Mr. Coburn is the only living Old Bill. The others were DeWolfe Hopper, James K. Hackett, Maclyn Arbuckle and Edmond Gurney. In the New York company, the late Mrs. Ivah Coburn played Victoire, the French maid.

So the years pass, with Coburn occupying himself on screen, stage, and radio, splitting his time between L.A. and New York.

Then, in 1959, the second-to-last mystery I found: his second marriage.

NY Times, 10/19/59

Charles Coburn Marries

LAS VEGAS, NEV., Oct. 18 (AP)—Charles Coburn, 82-year-old actor, dropping his famed monocle only to kiss his 41-year-old bride, today married Mrs. Winifred Jean Clements Natzka, widow of a New York Opera Company basso. The ceremony took place in the chambers of acting Justice of the Peace J.L. Bowler.

…and this leads to yet more questions. Did he marry for love, or for a tax deduction? He railed about tax rates in some of his late-life interviews, using the issue as a hook to promote You Can’t Take It With You, the show he was then touring.

And the final mystery: Most sources say this second marriage produced a child, a daughter. To which I say, seriously? Is an octogenarian Coburn supposed to have been up to siring a child? On the other hand, he managed to sire six of them 50 years before, and he was obviously a man of remarkable stamina. But perhaps his bride was pregnant by the opera singer who had widowed her, and that’s one reason why she was interested in marrying a man twice her age?

So, like Rosebud, none of these things definitively answer the riddle, Who was Charles Coburn? But they fill in some important blanks, they give us the flavor of his life in the New York theater, and the life he carried around inside himself when he made all those glorious movies we’re still watching.

And also like Charles Foster Kane, on August 30, 1961, death came for human dynamo Charles Douville Coburn, then 84, following minor surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. One obit said his wife and one of her two sons from her previous marriage were with him when he passed.

Not a word about the baby daughter, or, for that matter, any of the other six Coburn offspring, either in this obit as survivors, or mentioned a month later in a piece about his will and estate.

So if I ever get to have a cocktail with him in that cozy little bar in the sky, I’ll see if he can clear any of this up.

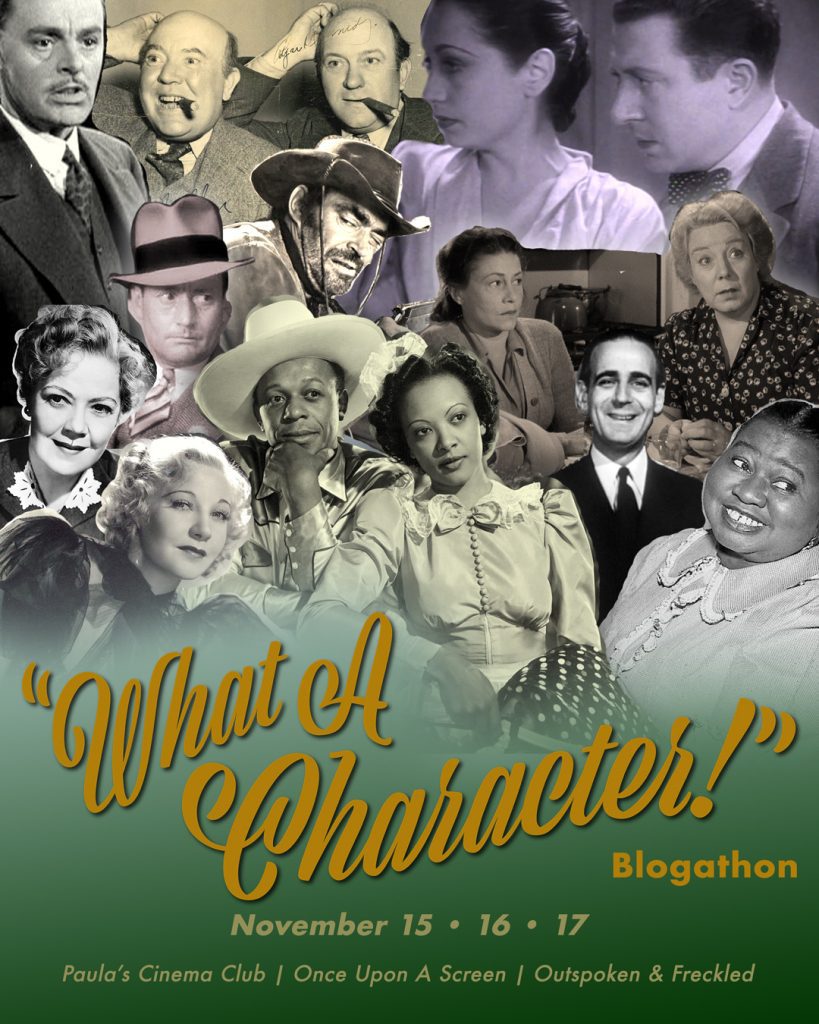

This was written for the 2019 What a Character! Blogathon, hosted by Aurora, Kellee, and Paula. Please go take a look at the other fabulous entries—you’ll be glad you did.

There is quite a character in the reality and the speculation of Charles Coburn.

Film fans are fortunate that there were such a variety of roles for him to play in the movies we enjoy to this day.

Your trail of research is as interesting as the man himself. Before reading your piece, I’d always assumed there was a Charles Coburn bio or memoir, and was surprised to learn there isn’t one.

And a second marriage! I had No Idea.

You’ve created a valuable resource here, on the life & times of Charles C. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Thank you very much.

The research made me want to go back in time (a not-uncommon wish for me) to see the New York of Coburn’s time, starting in 1906. Or to be a fly on the wall at the reunion party for The Better Ole in Hollywood in 1938…

I am trying to connect with whoever wrote this article. Charles Douville Coburn is my great Uncle. There is so much the public is not aware of. I would love to confirm the facts as I have a ton of memrobilia and articles that he wrote. He was extremely close to my grandfather Eigene D. Drummond and he was my mothers godfather. I have a ton of original letters he wrote along with a conspiracy surrounding his death.

Miss Carithers, I beg your pardon for not responding to this sooner, but…it has been some kinda year, hasn’t it?

I did answer an email from you, I believe, last spring, but if you replied, I missed it in my messy in-box.

I would be honored to discuss your great uncle with you. He was a great actor and had a remarkable life, and there are many things I would like to understand better from the research I was able to find.

Will search my in-box lest I missed an email, and hope you see this reply.

Hey there,

I own Carles Coburn’s house. Do you have any photos of his Hollywood boulevard house back in the day?

Charles Coburn was an acting hero of mine from boyhood (I celebrate my 74 year next month). He represented tradition and dignity as well as talent and accomplishment. I too look forward to sharing a cocktail and many great anecdotes with him in the little pub in the sky, some distant morning.

So down with that, as long as said little pub in the sky allows dogs, because I’m not letting my dear, departed doggies out of my sight when we meet again!

My first question for Coburn is, why did he remarry at the very end of his life?

What a life…

I live in a lovely area of Hollywood Blvd and it is a great place to live on. Does anyone know what his address was on Hollywood Blvd?