“An ant is what it is, and a grasshopper is what it is, and Christmas is a humbug.” —E. Scrooge

“

As so often happens when I choose a movie to write about, a movie I dearly love, I pass through a period of thinking there’s not really that much to say about it. That’s especially true with a story so often adapted and so universally beloved.

But of course as soon as I begin digging into the movie, its source material, and taking screen shots from the movie—can’t tell you how much I learn about a film during this stage—it invariably turns out there’s way too much to say and way too little time. I’m past my deadline already. That’s why this piece only goes through Scrooge’s first outing, with the Spirit of Christmas Past—I could happily spend another four hours doing screen shots, but this will hopefully whet your appetite for the greatness of this movie, if you don’t already know it, and get you ready for a re-viewing if you do.

So this will be not a finished essay but notes on an absolutely fabulous version of one of the most adapted stories in the English language. Also on my Christmas Carol watchlist: the George C. Scott version, which is regarded almost as highly as this 1951 version, and The Muppets’ Christmas Carol, which I have not yet seen. I’m taking for granted that you know the basic story and character names, at least the major ones (Scrooge, Marley, Bob Cratchit, Tiny Tim).

Christmastime looms large in Scrooge’s life. He was forged in the loneliness of his childhood at school, where he was left to fend for himself during the holidays. It was Christmas when his beloved sister, Fanny, rescued him from family exile and took him home, as she says in the movie, never to be lonely as long as she lives. It is Christmas Eve when Scrooge’s business partner and only friend Jacob Marley dies, and it is Christmas Eve seven years after that night when Dickens’ story takes place.

After a typical Christmas Eve, which for Mr. Scrooge means declining to make any donation to buy meat and drink for the poor (“I wish to be left alone,” he tells them) as well as telling a borrower who can’t make his payment to hie himself to debtor’s prison. “If they would rather die [than go to debtors’ prison], they’d better do it and decrease the surplus population,” and what seems to be a ritual of sneering at his clerk, Bob Cratchit, for his excitement about celebrating Christmas with his family, Scrooge has his customary solitary dinner. He shoos some tattered children carolers, singing in the snow, and walks to his house, the one he inherited from his late partner and friend, Jacob Marley. In the novella, Dickens says it is pitch dark, but that Scrooge knows every stone. But he is confronted by something he cannot account for: Marley’s face, lit by a dreadful light, appears on the door knocker…

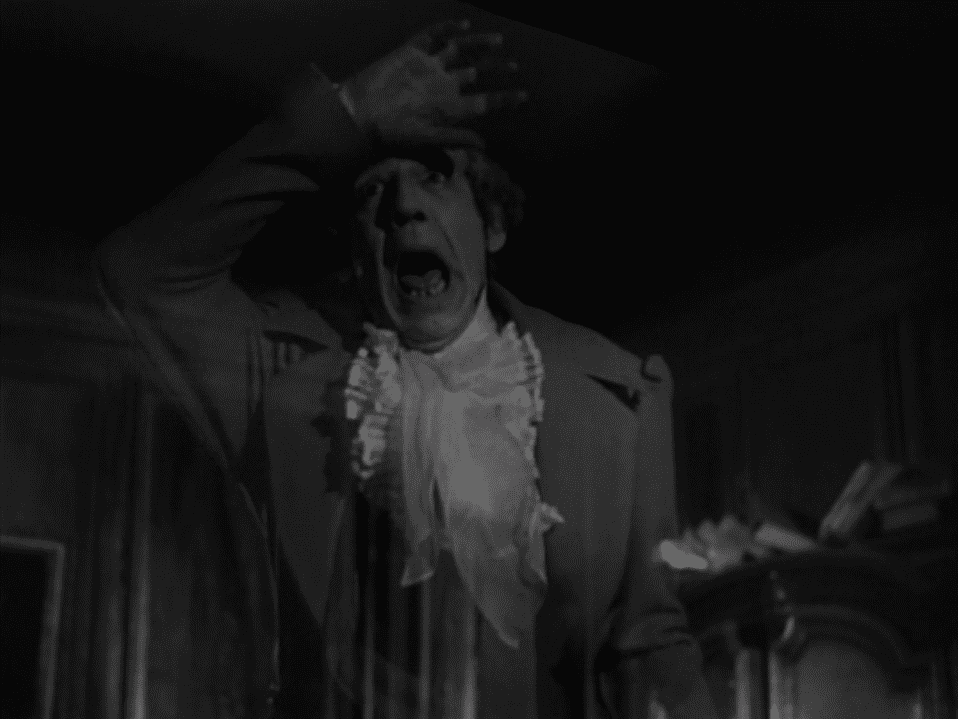

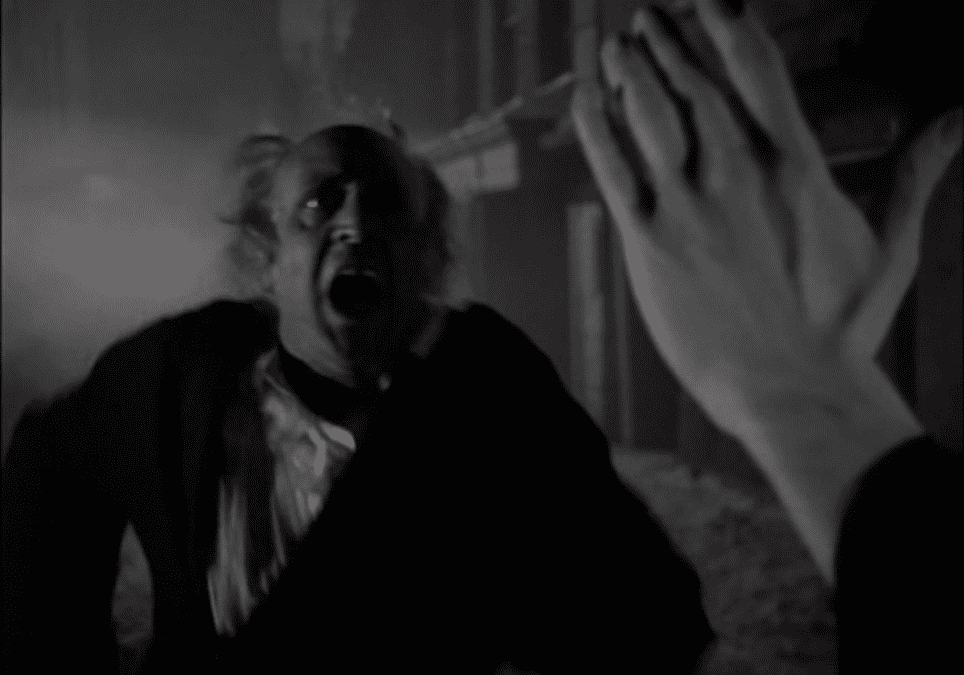

…followed shortly thereafter by Marley’s ghost. Marley’s afterlife is going very badly indeed, and it will never get better. Marley wishes to spare Scrooge his everlasting torment, so he intervenes to get Scrooge something he really doesn’t deserve—a chance to reform before it’s too late.

The film makes excellent use of sound in this section. Marley’s shrieks are blood-curdling, and his movements are accompanied by a sort of sloshing sound, as well as the very loud clanking of his horribly heavy chain, the one he crafted in life, day by day, “of my own free will,” as he says.

Just before he leaves, Marley calls Scrooge to the window and shows him spectral, writhing figures, those who want to help other but “have lost the power, forever.” The figures remind me of a Breughel painting. He also tells Scrooge to expect, courtesy of his own intervention, visits from three spirits, and makes clear that Scrooge had better avail himself of this opportunity to avoid Marley’s fate.

“I wish to be left alone,” Scrooge told the men who visited his office on this day, soliciting for charity.

But does he, really? He is in a kind of living death, his days and nights carved in routines and silence. His beloved sister is dead, his partner is dead, he has rejected his nephew, and has lost the love of his fiancée, which seems to remove the last impediment to his fully indulging his worst impulses.

On this particular Christmas, after years of an unvarying routine, in which Scrooge not only treats other people as an offense to him personally, he shows himself no more generosity or mercy than he does others. We see him at dinner, asking for more bread. The waiter clearly knows him, so he tells Scrooge the bread will cost a halfpenny more. Scrooge says, “..no more bread.” He starves everybody, but he barely indulges himself. The harsh world he perceives, in which he has become an instrument of that harshness, offers him no escape.

Scrooge and the Spirit of Christmas Past at Scrooge’s old school…

…they see Scrooge’s beloved sister, Nanny, who has come to bring Scrooge home for Christmas, at last reconciled with the father who blames Scrooge for his mother’s dying after giving birth to him.

She reassures him that everyone loves him very much, and promises him he will never be lonely again, as long as she lives.

Scrooge spent his early years in exile from his family, at school, unretrieved during holidays. A terrible, lonely childhood. He weeps when his sister Fanny comes to bring him home, his father finally having forgiven him for supposedly having caused his wife’s death (in childbirth). Scrooge retreats into this posture, finding an identity in his hardness, his borderline criminality (when he and Marley buy out the embezzler), his righteous, unending anger and feeling that he is the one being shortchanged, the one being cheated. He thinks it’s about money, a realm where he can be master. But it’s a hedge against the terror of loneliness, a kind of mastery of it. He mocks Cratchit’s closeness with his family, his excitement at celebrating Christmas with them. It rings so hollow.

After the school visit, the Spirit takes Scrooge to an office Christmas party thrown by his first boss, Mr.Fezziwig, a gentle soul who refused to harden himself to the increasing ruthlessness of the changing world. We see Scrooge dancing with joy, and we see old Scrooge smile for the first time. The Spirit asks why Scrooge gives Fezziwig so much credit for throwing a party that must have cost what, “three or four pounds,” and Scrooge, before passing his thought through his hate filter, says something like “But look how much joy he brought, it would be worth a fortune…” before trailing off, lowering his head in shame, and saying he would like to have a word with his clerk, Cratchit.

Earlier that evening, Scrooge had looked scornfully at Cratchit, who has just wished him a Merry Christmas: “A Merry Christmas, sir, and you a clerk with 15 shillings a week and a wife and a family. talking about Merry Christmas”—he sneers. “I’ll retire to Bedlam.”

“Perhaps the machines aren’t such a good thing for mankind after all,” Scrooge to the guy trying to buy out Fezziwig. This is the first scene where we see Scrooge tempted. The film frames many shots in doors and windows, people looking out at hard truths, or Tiny Tim looking in the toy store window at the Christmas display, or Scrooge’s fiancée Alice looking out at the world she now faces without Scrooge, who has changed in his affections, shifting them from Alice to making money at any cost.

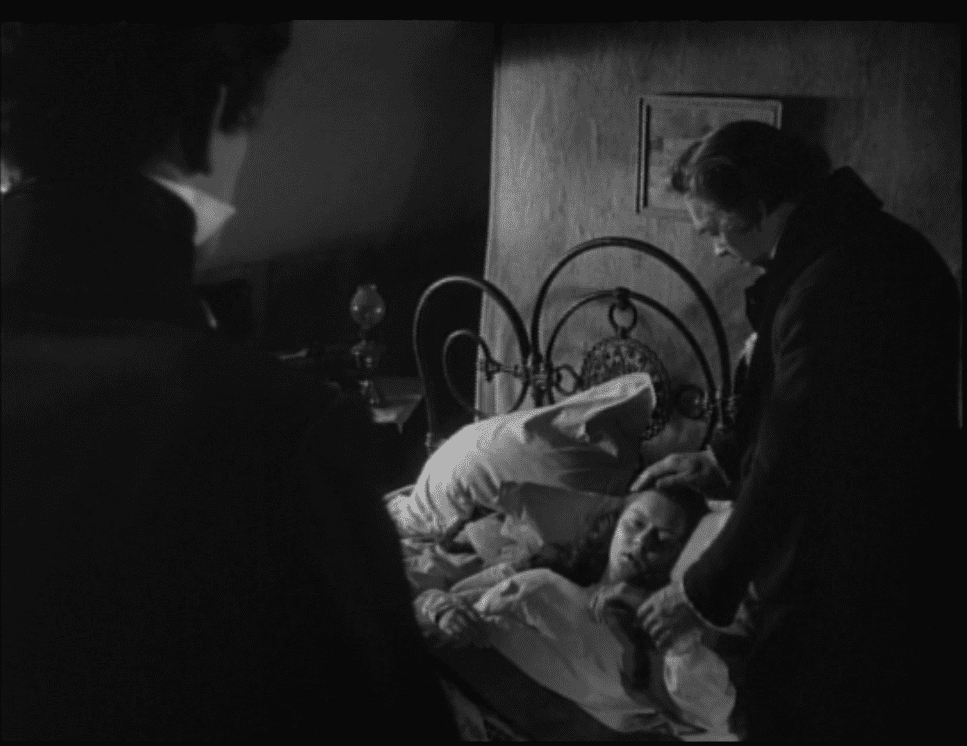

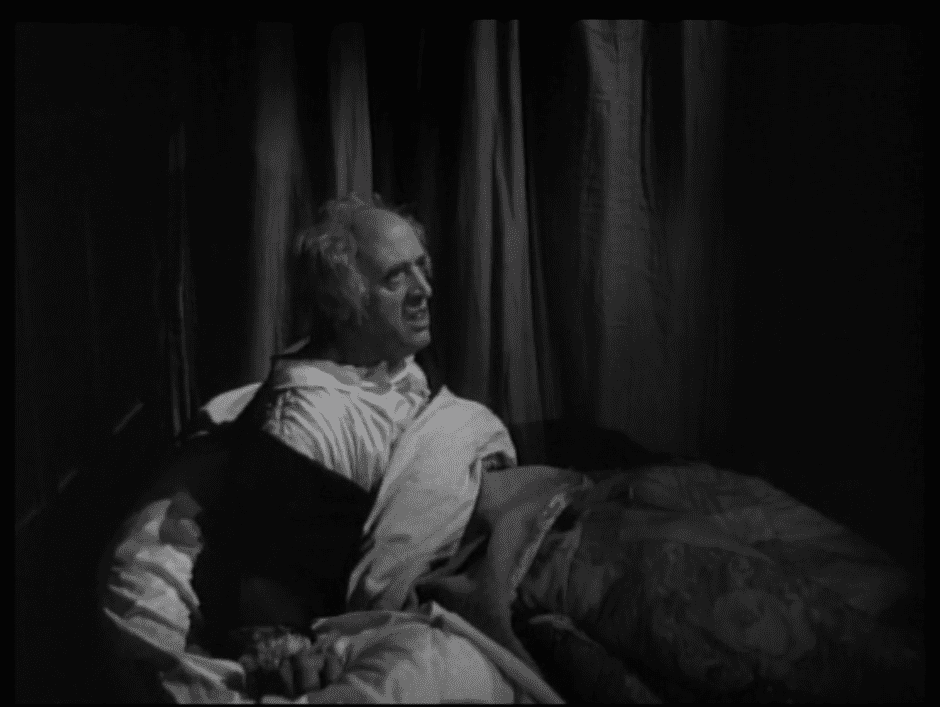

Sister Fanny is dying in childbirth, just as Scrooge’s mother did when she bore him.

Fanny’s deathbed: she whispers a demand that Scrooge promise he will care for her son (not sure why, where’s her husband?), so similar to Oliver Twist. (Q: Does this happen in the book? I don’t think so. But if it’s an addition to this adaptation, it’s an excellent one. It makes Scrooge’s antipathy for his nephew and the power of their final reconciliation much stronger.)

Then Alice breaks off their engagement. She is still the very pure, two-dimensional character she was in their first scene together. She is poor and kind, and Scrooge is becoming rich and has no time for kindness.

Alice, breaking off their engagement: May you be happy in the life you have chosen.

Scrooge, defiantly, angrily: I shall be.

Just after this, we see Scrooge reporting for work at his new job with the future embezzler. Scrooge seems to be hanging his head, he is ashamed to have abandoned Fezziwig. Proximity to the Fanny death scene creates a relationship—Scrooge changes, moves toward self-seeking and away from connection, because of losing Fanny and hating his nephew for causing Fanny’s death. He is introduced to Marley, who will cause his incipient corruption to flower.

The Spirit’s next stop after Fanny’s death and Alice’s breaking off their engagement: Scrooge’s new job, where he meets his future partner in business and corruption, and possible intercessor—it is Marley who has won Scrooge this last chance to avoid Marley’s tortured fate.

Marley: The world is on the verge of new and great changes, Mr. Scrooge. Some of them, of necessity, will be violent. Do you agree?

Scrooge: I think the world is becoming a very hard and cruel place, Mr. Marley. One must steel oneself to survive it and not be crushed under.

Marley: I think we have many things in common, Mr. Scrooge.

Scrooge: I hope so, Mr Marley.

Bob Cratchit, to Mrs Dilber, who has come to fetch Scrooge because Marley is dying. “He’ll come at seven.”

Mrs Dilber: “I’ll try to get Mr Marley to hold out till then, I’m sure. Much obliged…and a Merry Christmas, if it ain’t out of keeping with the situation.”

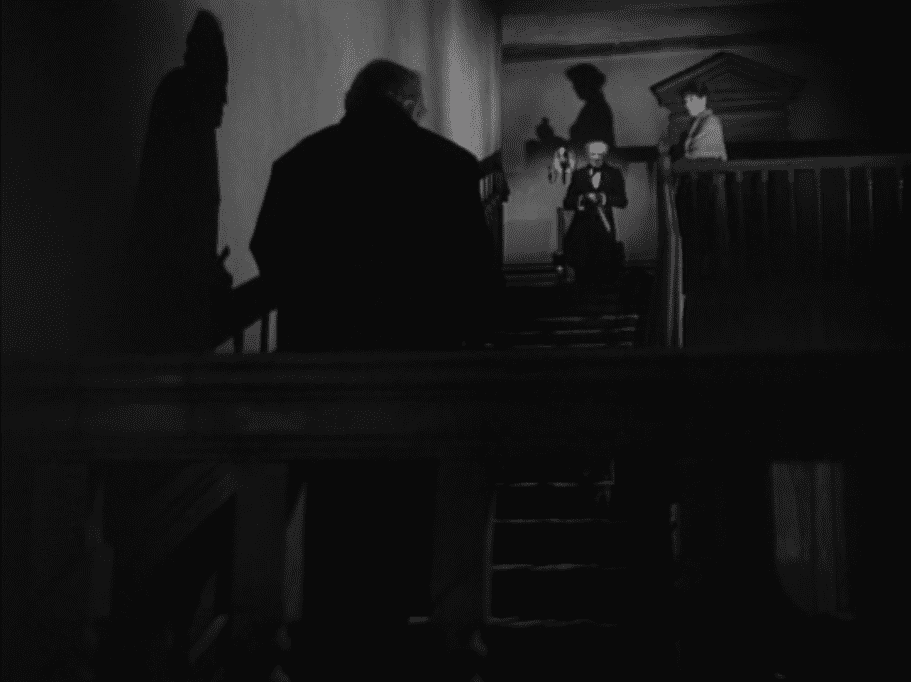

Scrooge climbs Marley’s stairs, to Marley’s deathbed. At the top: the undertaker, played by the marvelous Ernest Thesiger, best known for his appearances in two James Whale films, The Old Dark House (1932) and as Dr. Frankenstein’s fellow mad scientist Dr. Pretorius in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

Ernest Thesiger as the undertaker

Scrooge: You don’t believe in letting the grass grow under your feet, do you?

Undertaker/Thesiger: “Ours is a highly competitive profession, sir.”

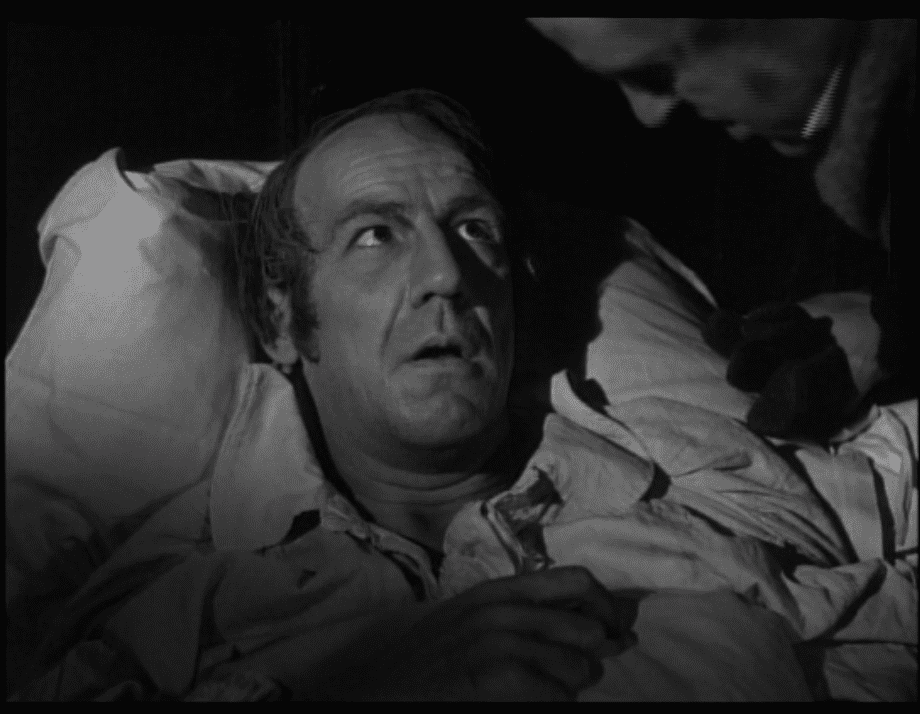

“We’ve been wrong.”

“…Wrong? Well, nobody can be right all the time. Nobody’s perfect. We’ve been no worse than the next man…or better, when it comes to that. You mustn’t reproach yourself, Jacob.”

“We were wrong. Save yourself.”

“Save myself…save myself from what?”

Marley expires having failed to make Scrooge see the peril he is in.

Mrs. Dilber turns to the undertaker: “Just like you said.”

Undertaker: “I always know”.—funniest moment in the movie, reliably from Thesiger.

Spirit: Jacob Marley worked at your side for 18 years. He was the only friend you ever had. And what did you feel when you signed the register at his burial and took his money, his house, and his few mean sticks of furniture? Did you feel a little pity for him? Look at your face, Ebenezer, the face of a wretched, grasping, scraping, covetous old sinner.”

“No…no…”

The clock tolls, Scrooge wakes up, the next Spirit is coming…

This was written for the Happy Holidays Blogathon, hosted by the good people at Pure Entertainment Preservation Society.

I have watched this film every Christmas Eve since childhood (mainly thanks to Canadian television screenings, now my own tape and DVD). I could, without too much trouble, do some addition and subtraction and come up with the exact number but I believe it would be too upsetting for a woman of my age!

Reading of your regard for this movie, and sharing those scenes with you, all of the voices came to me vividly and the chills of some scenes and the tears that come with others. Thank you.

Christmas Eve is rushing toward us and I will not try to hold it back.

Hey Patty,

That is without question the most beautiful comment it has ever been my honor to receive.

Thank you kindly…and to you and yours, a very Merry Christmas!

Hi, on an unrelated note, I nominated you for the Sunshine Blogger Award. I love your blog and think your reviews are fabulous. My favorite is your piece on Laura.

Thanks, Margot, thank you kindly!

Thanks, Margot, I might have already been nominated…

Thank you very much—I don’t write anywhere near as regularly as I’d like, but it’s so encouraging that once in a while somebody like you comes along and notices. One of the things I love about this writing is, I learn so much about the movies in this process. By the time I was done writing, my whole understanding of the movie had changed.

Trying to manage at least one blogging event a month this year, wish me luck! Hopefully I’ll write more stuff you enjoy…

It is beyond me why I have never seen this version. But, thanks to you, I am going to watch it this year. And I know I’ll love it.

Glad to steer you to it!

Did you get to see it? Would love to hear your thoughts when you do…

“I always know!” is part of my regular lexicon. And when the therapist helped me stand the morning after my hip replacement, my husband said to me “Bravo, Uncle Scrooge!”. The therapist looked at him and said “Did you just call him Uncle Scrooge??”. Love this movie. Love it, love it, love it!!

I have this DVD and it is Colorized and my sons and I watch it each year in December. It always, overwhelmingly reinforces the true nature of why God gave us the Gift of Life and as He prospers us, we are to give generously to the poor and down trodden.

I am going to have the picture of Jacob Marley on his deathbed Framed, and hung in my office. Watching him struggle to get those three words out to Ebenezer haunts me in a good way, each day.

I have learned to invest in crypto currencies and am trusting God to immensely bless my investments. My goal is to build 16,000 Tiny Homes for the homeless and elderly under-income souls about me.