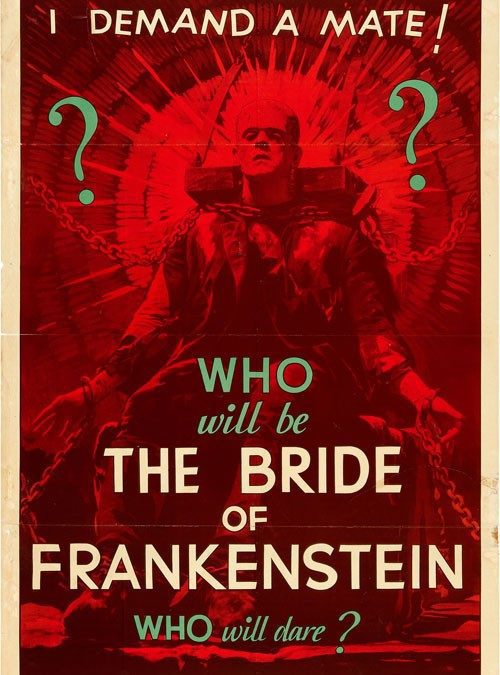

Eighty years after its original release, James Whale?s?The Bride of Frankenstein?just keeps getting better

That wasn?t the end at all?. Would you like to hear what happened after that? I feel like telling it?. It?s a night for mystery and horror. The very air is filled with monsters. ??Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (Elsa Lanchester), setting up the story in the prologue,?Bride of Frankenstein

How often is a sequel as good as the original? Not very. How often is a sequel better than the original? Almost never. But?The Bride of Frankenstein?(1935) is widely acknowledged as not just superior to its parent,?Frankenstein?(1931),?and not simply one of the best horror movies ever, but transcending its genre to sit securely among the greatest films ever produced in Hollywood.?The Bride? is one of those movies that was recognized as exceptional on its original release (at least by most critics; Graham Greene, then a cranky film critic in England,?hated?it) but many feel that the years have only burnished its brilliance.

If this sounds like hyperbole, bear with me. You might not be into horror, so perhaps you think the best horror movie couldn?t be that good. Maybe you?ve seen?Gods and Monsters,?the 1998 biopic about James Whale,?BOF?s director, in which?BOF?figures prominently, and you think that pretty well covers it? Then there?s Mel Brooks?s classic parody, which is mostly based on?BOF?(rather than on?Frankenstein). Perhaps you?ve seen?BOF?and enjoyed it as a cherished bit of camp, a quaint little movie that?s reliably entertaining.

As a matter of fact, movies like?The Bride?,?whose rich iconography was long ago seamlessly woven into popular culture, can be hard to really?see?what we already know or think we know about them keeps us from seeing what?s actually there. We superimpose the movie in our heads over the one on the screen, and we miss the glories and extraordinary pleasures of the real thing.

So we?re going to peel away the layers of familiarity and talk about?The Bride of Frankenstein?(hereafter referred to as?The Bride??or?BOF) not just as we think we know it, but in its full glory.

The film?s action is divided into three acts.

Act I: The brief prologue with Mary Shelley, her husband Percy the poet, and their pal Lord Byron serves as the sequel?s setup.

We see the fire at the mill that ended the first movie and find out that the Monster has somehow survived, though scarred and with a case of PTSD from the trauma of the fire (and everything else). So has Henry Frankenstein, who plans to wed beautiful Elizabeth and decamp, putting all this nonsense behind him (the statute of limitations must be really short in their country). But Henry?s old professor, Doctor Pretorius, shows up and talks Henry into visiting his laboratory, where he too has succeeded in creating life?miniature people in glass bottles, a charmingly done special effect.

Pretorius is determined to convince Henry that they should collaborate to make a mate for the Monster, perhaps leading to a race of monsters they can control.

Pretorius: Leave the charnel house and follow the lead of Nature ? or of God if you like your Bible stories. Male?and?Female created He them. Be fruitful and multiply. Create a race, a man-made race upon the face of the earth?. Why not?

Henry:?I daren?t?I daren?t even?think?of such a thing.

Pretorius:?Our mad dream is only?half?realized. Alone, you have created a man. Now together, we will create his mate.

Henry:?[looking dubious] You mean??

Pretorius:?Yes. That should be?really?interesting.

Act II: Meanwhile, the Monster has been roaming the countryside, enraged and terrified, killing a few people here and saving a shepherdess from drowning there. He is shot by a hunter, captured by the villagers, bound to a pole in a series of distinct Crucifixion images, and chained in a basement. When he gets his bearings he tears the chains loose and roars back into the hostile world. He kills a little girl and an old couple, terrifies a Gypsy family and again burns himself trying to grab the chicken they were roasting.

He just saved the shepherdess from drowning, then she freaked out and the hunters shot him. So he flips them the bird.

Then he hears a violin playing not far away in the woods. The music draws him; he smiles, and we realize it is for the first time.

He follows the sound to the hut and is taken in by the blind hermit who lives there. The hermit, unable to see the Monster, treats him with kindness and courtesy; it is the first time anyone has done so, and the Monster for the first time experiences feeling safe and wanted. The hermit feeds him and puts him to bed, saying he has often prayed for God to send him a friend. They both weep.

The hermit teaches the Monster to speak (?Alone bad. Friend good?), to enjoy a cigar and a glass of wine. But the Monster?s happiness is short-lived: Two more hunters (one is played by John Carradine) show up and tip off the hermit and raise a gun to (again) shoot the Monster, who accidentally sets fire to the hut. They lead the hermit away while the Monster screams, terrified, trying to escape the fire (another fire!). He stumbles out through the flames plaintively muttering ?Friend??

Another Crucifix: Originally the Monster was supposed to try to pull Jesus off the cross, thinking the statue was suffering as he had at the hands of the villagers. The Hays Office nixed it, but Whale still got his imagery with this new shot.

One step ahead of the torch-bearing villagers, the Monster hides in an underground crypt and there meets Pretorius, who has come looking for a promising female skeleton for his and Henry?s science project (?I hope her bones are firm!?) but has stayed to have a little midnight supper of roast chicken and wine, which somehow always tastes better in a crypt.

The Monster approaches, wistfully asking: ?Friend?? Pretorius convinces the Monster that he is going to provide him with a woman. The monster is in: ?Woman. Friend. Wife.? When the two call on Frankenstein to force him to help, he refuses until the Monster kidnaps Elizabeth.

Act III: The climactic laboratory sequence, a tour de force so influential that you probably remember it even if you?ve never actually seen this movie. Things have now gone completely bonkers: When Henry needs a new heart, young and very strong, Karl (Dwight Frye) lurks on a dark village street until a girl passes by? Henry is barely keeping it together but still pauses, wondering where the heart came from. But?back to work. The experiment has?now careened so far out of control that Pretorius, for whom blackmail and kidnaping are standard operating procedure, is now casually commissioning murders, shrugging that Henry will pay the 1,000 crowns for the heart.

Waxman?s underscoring, built upon the beating heart?s pulse, is delirious, as is the editing and the cinematography with its skewed framing and Rembrandt effects (very dark backgrounds with faces lit from both front and side). As the storm rises Henry?s and Pretorius?s excitement rises with it, as does the Monster?s anxiety. The laboratory is filled with fantastic fake equipment, made to order by the Universal prop department. There?s a crescendo of music, distorted closeups, flying sparks, flashing lights, smoke, flames, ? The whole thing could be Henry?s feverish dream?the earlier part of the movie is realistic by comparison to this, in which we seem to be simultaneously inside the disordered minds of Henry, Pretorius, and the Monster. In a fit of pique, the Monster tosses Karl off the roof. Lightning strikes one of the incredible kites, and voila, the Bride is born.

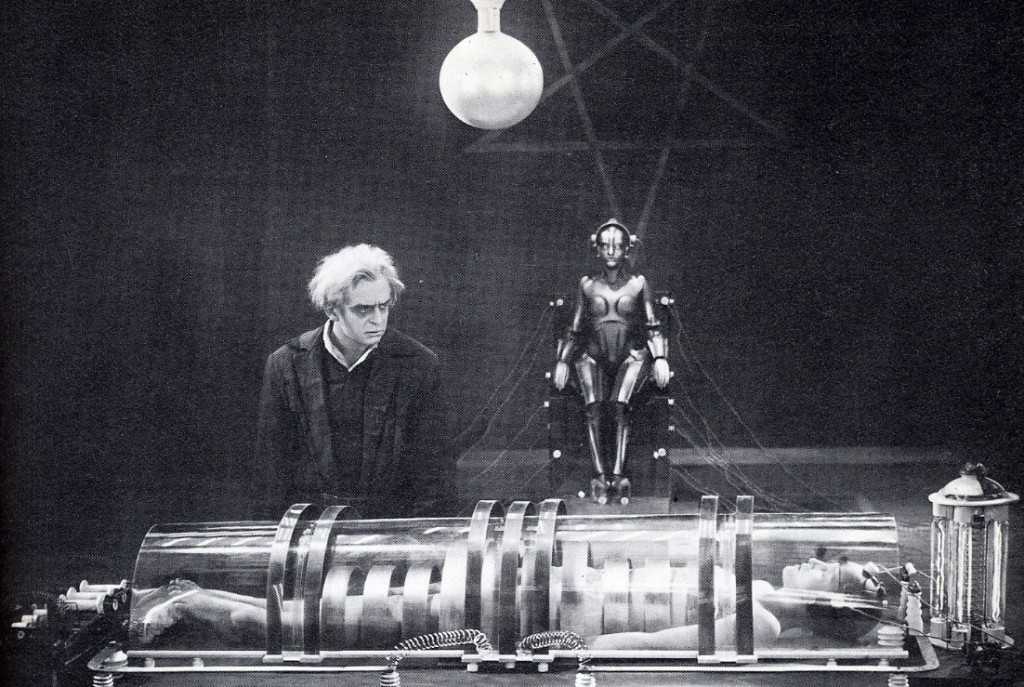

I always wonder, did mad scientists get their amazing lab equipment mail order, or did they build it themselves from kits? Pretorius?s lab is a dream come true for a deranged megalomaniac.

?She?s alive, alive!? unhinged Henry cries exultantly, and he and his partner unwrap her mummy bandages so they can get her ready for her closeup. Lanchester writes in her memoir that when they shot the closeup of her eyes in the bandages she really was suffering, having to hold her eyes open for minutes at a time till they got the shot.

Pretorius in his brief moment of triumph: ?Behold, the brrrrride of Frrrrankenstein!? ?with jazz hands.

Now the Bride is unveiled to us, in her bridal gown / surgical gown / shroud, her Nefertiti hair with the two lightning shocks of white, demure Mary Shelley?s face electrified, robbed of speech. The Monster comes in, approaches her?hopefully:??Friend?? She screams. He knows it?s useless, but he tries again, smiling, shyly patting her hand. She gives him a look of pure disgust. His face crumples. It is among the most painful rejections I have ever seen.

?She hate me. Like others,? he snarls. ?Don?t touch that lever, you?ll blow us all up!? Henry screams. (Apparently somebody thought it was a good idea to install a lever that if pulled will blow the joint up.) Elizabeth is pounding at the door, pleading for Henry to come with her. The Bride is hissing like a swan in Regents Park, which is where Lanchester learned it.

The Monster says to Henry, ?You go, you live!? He looks at Pretorius and the Bride. ?You stay. We belong dead.? I never noticed until writing this that the Monster weeps twice in the film: First at the hermit?s hut, and then when he decides to blow himself and the Bride and Pretorius. He pulls the lever. The castle explodes. Ludicrously, in the .5 second interval, Henry and Elizabeth cover half a mile and see the explosion from a safe distance. ?Darling!? Henry says to Elizabeth, as if now they can get back to normal.?Sure.

As Glenn Erickson says in his review at DVDTalk: ?Whale juggles and balances a tall stack of odd content and self-aware references: operatic excess, melodramatic plotting, black humor, necromantic humor, political comment, anti-clerical jabs, parodies of classical paintings, German Expressionistic sets, Russian montage editing and pure cornball sentiment.?

In?BOF?we have all the elements: an intelligent, witty script that juxtaposes wry humor with the macabre; its own look, beautiful and strange, eclectic in its design and imagery, created by cinematographer John J. Mescall, art director Charles Hall, master makeup designer Jack Pierce; Franz Waxman?s score, as lush and varied emotionally as the film itself; and, as the closing credits remind us, A GREAT CAST IS WORTH REPEATING?felicitous casting in all the main roles, including Colin Clive repeating his Baron Henry Frankenstein from the original; luscious 17-year-old Valerie Hobson as Henry?s fianc?e, Elizabeth; Una O?Connor as Minnie, the comic relief, voice of the bloodthirsty villagers and of the anxious audience; and especially Whale?s theatrical mentor Ernest Thesiger as the Mephistophelean Doctor Pretorius, the engine that drives the fever-dream plot. Boris Karloff gives an extraordinarily expressive performance that covers every state from from homicidal rage to tenderness to self-loathing, childlike delight to suffering to unbearable loneliness, and finally Elsa Lanchester in the dual role of winsome Mary Shelley, author of the source novel, and the unforgettably unsettled and unsettling, beautiful, hissing Bride herself.

All those elements deftly orchestrated by director Whale (Jimmy to his friends), who also gives the movie something very rare: a Monster who changes and grows as the narrative unfolds, and an iconic female Monster (the only one in classic film) who refuses to accept the role for which she was created.

BOF?invites all sorts of readings. There?s the film?s own professed one, here attributed to Mary Shelley, the cautionary tale about a man who, as the saying goes, ?tampered in God?s domain.? There?s the psychoanalytical one, in which the Monster is the return of the repressed, or Henry Frankenstein?s own id, the deeply repressed hostilities that lurk beneath the surface (though to be honest, Henry?s surface could use a little healthy repression) ? There?s the family systems one, in which the Monster is Frankenstein?s unwanted child, who reacts to being rejected by lashing out, killing?

And then there?s the one I?m currently partial to: The monster, trapped in a world he never made, learns to speak and finds language for his loneliness, his bitterness, and his yearning, learns to appreciate music and food, learns to engage in manly pursuits like smoking and drinking, learns to be a friend, learns to use his destructive powers to compel others to do his will?.?And the Bride, who is almost never discussed beyond her appearance, wrenched into being to serve others? agendas: The Monster?s loneliness and the mad scientists? perversity and desire for world domination. She refuses to be their instrument, and somehow?she?s?the bad guy. Typical.

The Monster learns, finally and tragically, that no one, not even another creature made as he was?on a surgical table, brought to life with electricity?and created expressly to be his lover and perhaps the mother of his children, can ever love a big homely weirdo like him.

The Bride??has been written about extensively, including a chapter in?James Whale, the biography by James Curtis, Bill Condon?s film?Gods and Monsters,?a BFI Film Classics Guide by Alberto Manguel, and countless references in other books and articles, along with a variety of online reviews and a documentary and commentary on some DVD and Blu-Ray editions.

But the one voice we will never hear is the one I most long for. James Whale died in 1957, more than a decade before Kevin Brownlow and Peter Bogdanovich and other film historians began interviewing the filmmakers from Hollywood?s rich past. Whale had retired from the movie business in 1941, financially secure, to turn his creative energies to painting. He was done with the film business; the studio system could no longer provide him with the kind of creative freedom and control he found necessary?he was not temperamentally suited to being a factory employee, even in the most glamorous factories in the world. What might Whale have been able to tell us about his creative process in making?BOF, and what stories did he take to his grave about his experiences and recollections of the production??Then again, it?s possible he wouldn?t have wanted to talk about it?he was an extremely private man.

Whale left us just as television was beginning to create a whole new generation of fans for his Universal horror films. He might be dismayed the way Lanchester was in her later years, that children in the grocery store recognized not her but the Bride, all those years later. The last thing Whale wanted was to be pigeonholed as a horror director?he wanted to make all kinds of movies. The great success of first?Frankenstein?and then?The Old Dark House?and?The Invisible Man?gave him bargaining power with his bosses at Universal, who agreed to let him make one film of his own choosing for every horror film he directed.

James Whale was determined not to make a sequel to his 1931 hit, and with that firmly in mind he concluded the movie by burning up Doctor Frankenstein and the Monster. Silly man?since when has certain death ever precluded?a sequel? Whale had been brought to Hollywood because of his experience directing dialogue. He aspired to be an A-list director, to make the big budget, prestige movies. When?Frankenstein?was a huge success with boffo box office, making veteran character actor Boris Karloff an international star overnight, the writing was on the wall?the executives at Universal were not going to pass on a sure thing. Whale was under contract and on the hook. A script was ordered and discarded, then another and another, dull or ridiculous affairs like the one that had Henry?and Baroness Frankenstein on the lam with a traveling circus, a la Freaks. But finally John L. Balderston and William Hurlbut came on as writers, and Whale was able to cobble together a script he considered workable.

Whale knew Elsa Lanchester from the theatre scene in London, and he decided to cast her in the dual role of the female monster and of pretty, demure?Mary Shelley, in a very odd prologue. Thus Lanchester bookends the movie, appearing in its first and last moments, first as the creator of the story itself and then as the latest creation of the mad scientists. The Bride is cobbled together from a fabricated brain, the heart of a young girl murdered for it, and other miscellaneous body parts that were lying around. She?s supposed to be evil.

Whale?s creative breakthrough seems to have been his decision to cast Lanchester in the dual role. Somehow Elsa bookending the film, opening it as the author and ending it as the unwilling Bride, gave him the scaffolding he needed to build the film, to breathe such remarkable invention and emotion into the whole enterprise.

The success of his previous horror films earned Whale a much bigger budget this time around, as well as full creative control, and he took advantage of both to the hilt. He had the luxury of time to supervise fantastic set designs, to plan his set-ups, to commission a career-making?score from Franz Waxman. He could consult with Jack Pierce on?the Monster?s makeup, which not only has details like scars from the fire, but actually changes four or five times throughout the course of the film: His hair gets longer as the film progresses.

Creation rising from the waters, Prometheus bringing fire: The movie is filled with drownings and burnings, as were the lives of Frankenstein?s creator and her husband in real life. Before Shelley got his divorce and was free to marry Mary, she tried to drown herself; Shelley?s wife did successfully drown herself; then Shelley also perished in an accidental drowning? In the 1931 film, the Monster (accidentally) drowns the child Maria, then in?BOF?he drowns Maria?s parents in the first moments of the film, emerging from the underground river where he escaped the fire? ?then a few scenes later, the Monster?saves a shepherdess from drowning? The hermit uses the Monster?s antipathy to fire to teach him the concept of good / bad. The hermit?s hut catches fire as the Monster struggles with the hunters? The laboratory has lots of jetting flames during the climactic sequence? And of course there?s the final explosion, which Henry and Elizabeth escape, paving the way for the next sequel.

Here in the 21st century we are fixated on realism, the flattening out of imagery. We privilege it, we denigrate the obviously theatrical. W e even want our fantasies to look ?realistic.? Let?s get one thing straight:?The Bride of Frankenstein?is no more interested in realism than?Metropolis?or?The Wizard of Ozor?Babe?or?Oklahoma!?or?Footlight Parade. Or, for that matter,?Bringing up Baby?or?The More the Merrieror?Duck Soup.

Roger Ebert discusses the liberating quality of horror movies:

?One advantage? is that they permit extremes and flavors of behavior that would be out of tone in realistic material. From the silent vampire in?Nosferatu?(1922) to the cheerful excesses of Christopher Lee?and Peter Cushing?in Hammer horror films of the 1960s, the genre has encouraged actors to crank it up with bizarre mannerisms and elaborate posturings. The characters often use speech patterns so arch that parody is impossible.

?The genre also encourages visual experimentation. From?The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari?(1919) onward, horror has been a cue for unexpected camera angles, hallucinatory architecture and frankly artificial sets. As mainstream movies have grown steadily more unimaginative and realistic in their visuals, horror has provided a lifeline back to the greater design freedom of the silent era. To see sensational ?real? things is not the same as seeing the bizarre, the grotesque, the distorted and the fanciful. There is more sheer shock in a clawed hand unexpectedly emerging from the shadows than in all the effects of?Armageddon, because?Armageddon?looks realistic and horror taunts us that reality is an illusion.?

Ebert says that as movies have become duller and more realistic we have lost something crucial.?BOFis more poetry and music than anything else. We have this tendency to insist on realism, and?BOF?is one of the great horror films because it has no interest at all in realism. Do we treat the imagination as something to be rationalized out of existence, to be tamed away from its irrational desires and fancies?

Manguel discusses the history of myths about creating life and the tradition of excluding women from the process:

?Creating from male ?seed? creatures in his own image (as Pretorius does in his glass jars), with no need for a woman (as Doctor Frankenstein realizes), is the alchemist?s method, the patriarchal dream, the mad scientist?s goal. From the Jewish golems to the animated sculptures of fable and science?Eve created out of Adam?s rib, Pygmalion?s ivory woman, Collodi?s Pinocchio, the 18th- and 19th-century automata that so enchanted Mary Shelley?s circle, Dr. Pretorius?s homunculi?men have imagined themselves capable of creating life without women, depriving women of the exclusivity of the power to conceive. No women take part in Henry Frankenstein?s creation of the Monster, or later in that of the Bride: It is an affair conducted only among men.?

Whale modeled the Bride on the evil robot Maria from?Metropolis, played by Brigitte Helm (who Whale considered casting as the Bride). The table where the Bride?is created bears more than a passing resemblance to the Maria?s laboratory birthplace.

Again, Manguel:

?The Bride is a femme fatale. She has been brought into a realm of power-thirsty patriarchs anxious to people the world with their creations. In their eyes, she does not exist for her own sake: She is merely a female counterpart to the Monster?maybe the future mother of a monstrous litter bred by more traditional methods, but primarily a living doll created for the Monster?s pleasure. In this world of men, the Bride is damned if she does and damned if she doesn?t. Were she to consent to the coupling, she?s be a complacent whore; unwilling to submit to what she is told is her duty, she becomes a reluctant whore, and an instrument of male perdition. Because of her refusal, the jilted Monster brings the drama to its apocalyptic conclusion.?

Originality is not an easy burden to carry. David Thomson said of Lanchester, ?It is a sad reflection of Elsa Lanchester?s originality that this fierce beauty is probably the bext-known work she ever did.? And Andrew Sarris wrote of James Whale that ?Whale?s overall career reflects the stylistic ambitions and dramatic disappointments of an expressionist in the studio-controlled Hollywood of the ?30s.?

In the end, both the Monster and the Bride are outsiders, created for others? purposes and left to fend for themselves in a world that will never accept them. Sarris quotes Grierson, who noted in the ?30s that the torch-wielding mob in?BOF?reminded him of a lynch mob. Whale was also an outsider, a misfit, too much an individual and artist to accept the corporate dictates of studio work. He was also a gay man and the son of a factory worker.

The Bride of Frankenstein?is one of those oddities that through the coordinating intelligence of its director became something more than the sum of its parts. It offers no moral injunction. It draws us into sympathy with a serial killer and child murderer, it forces us to identify with his terrible loneliness and fate. And it does so with such wit, such humor, and such audacious beauty that we don?t even realize we?re bleeding across moral borders.

Perhaps it?s compassion that distinguishes?The Bride of Frankenstein,?that lifts it above even the sum of its fine creative elements to the level of art and accounts for its great power 80 years after its original release. Whale created a Monster whose most astonishing quality is not his brutality but the soul he bares when he hears music for the first time, and smiles.

Check out the film on Amazon |

Check out the book on Amazon |

Check out the book on Amazon |

This post was written for the Classic Movie Blog Association?s 2015 Spring Blogathon. Go read more of the incredible posts?here.

Also: I am pleased to announce that this post is included in the ebook?The Fabulous Films of the 30s,available at?Amazon?and?Smashwords. Proceeds will be donated to film preservation organizations.

What is the name of the cemetery shrine used in the Bride Of Frankenstein?

I didn’t know it had a name…. Sorry I can’t help you, but if you find out please let me know?I’m interested.