“My mother didn’t think Leslie was suitable for a Vale of Boston. What man is suitable, Doctor, she’s never found one…. What man would ever look at me and say ‘I want you’? I’m fat. My mother doesn’t approve of dieting. Look at my shoes. My mother approves of sensible shoes…. I am my mother’s well-loved daughter. I am her companion. I am my mother’s servant…. My mother says…. My mother, my mother, MY MOTHER!”

On the set with Paul Henreid. Looks like she’s reading a script?maybe they’re running lines.

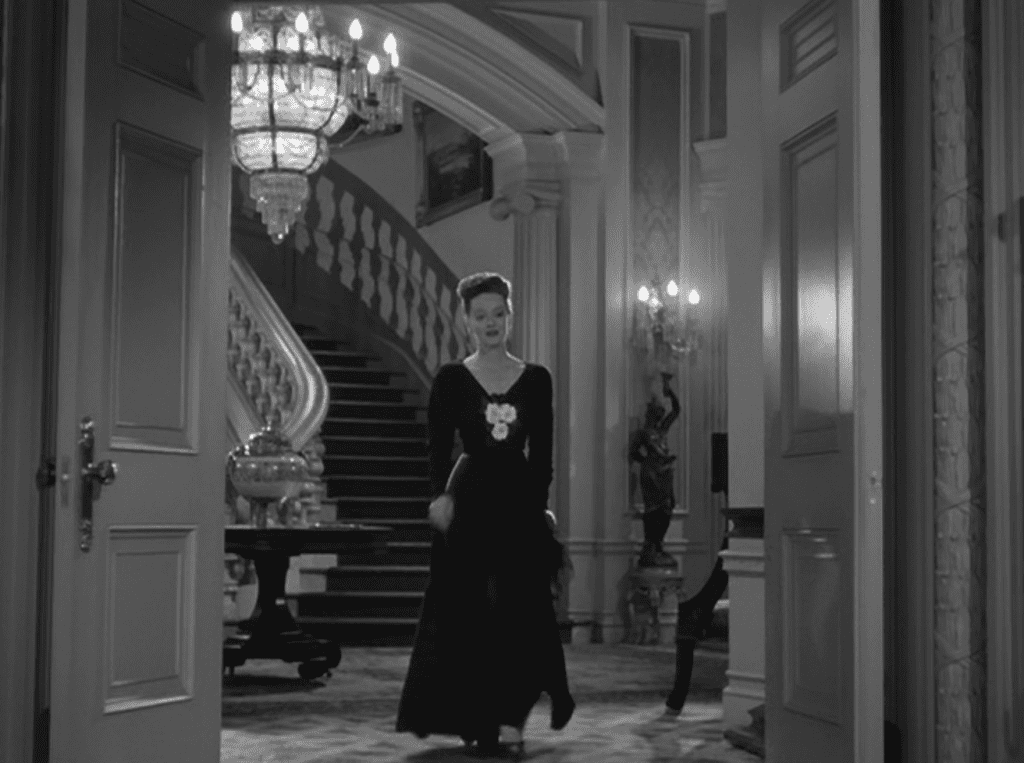

When we first meet Charlotte Vale, who is having a nervous breakdown, she is saddled with both bushy black brows and unnecessary eyeglasses?two of Hollywood’s stock ways of telegraphing: unattractive. She’s also supposed to be fat, and she’s dressed as unflatteringly as her monstrous mother can make her, in a hideous print dress and a pair of those ghastly sensible shoes Charlotte so despises.

Which means she’s only a good tweeze and a trip to Bergdorf’s away from being unrecognizably chic. That and a “very clever doctor” Charlotte finds in South America who gets 20 pounds off her.

Mother-approved, sensible shoes.

Post-Cascade, non-Mother-approved pumps.

When the movie starts Charlotte’s kindly sister-in-law is about to stage an intervention, with my all-time favorite movie psychiatrist, Dr. Jacquith (Claude Rains, also one of my favorite imaginary fathers). They have their work cut out for them, gaining Charlotte’s confidence and convincing Mother that “my little girl” is actually dangerously ill, and that not getting her some serious treatment will reflect poorly on the Vale name (she wouldn’t even consider such a thing out of concern for her daughter). They succeed, and Mother allows Charlotte to spend a few months at Jacquith’s sanitarium, Cascade.

Charlotte faces “the fork in the road,” asks Jacquith if he can help her.

And Cascade, rustic and cozy in the Vermont woods, and some psychotherapy with Jacquith, do the trick. Hell, just being away from Mother worked wonders. But of course Charlotte dreads going home, and again the sister-in-law steps in with a plan to let Charlotte try her wings, on a South American cruise.

“Could we try to remember that we are hardly commercial travelers? It’s bad enough to have to associate with these tourists on board.” ?Mother

Charlotte had confided to Jacquith during the intervention about her last cruise with Mother, when Charlotte was 20. Her shipboard romance with a handsome young officer (see photo at top), inevitably foiled by Mother, was her last hurrah until now, This post-Cascade cruise is a redo of that previous idyll, and for the second time Charlotte will fall in love with a man she meets onboard. Charlotte has good luck on ships. Maybe it’s the fresh air.

Now, Voyager is one of the great “women’s pictures,” that most derided of genres. It is a bit of an outlier, though, subverting some of the genre’s conventions. The theme of a woman who finds her own voice and authentic self is not common in the 1940s. Much more common were the movies Ginger Rogers seemed fated to star in, where her unhappiness is revealed to be the fruit of her being a successful career woman, who needs to subordinate herself to a man to find true happiness. But in Curtis Bernhardt’s My Reputation (1946) and NV, the protagonists find themselves unable to hew to the conventions of their milieu, forced to defy their families’ and communities’ expectations. Neither Charlotte Vale or Jess (Barbara Stanwyck) in My Reputation are bomb throwers?they’re not out to bring down the patriarchy or challenge inequality or injustice. But in a time of rigid conformity, they’re still pretty damned brave.

Another spectacular Orry-Kelly gown, which bloodless Brahmin Elliott appreciates but finds too hot to handle.

NV?depicts Charlotte’s severe depression fairly realistically, and Davis portrays it in all its complexity. The novel’s author wrote from her own experience of a breakdown, and Charlotte’s behavior?eyes cast down or darting like an animal’s, a jumble of emotions rattling just beneath her anxious surface, is agonized and confused. it’s as though she’s functioning by rote, trying to act normal with only the sketchiest sense of what that looks like, aching and exhausted, without a shred of confidence that she can find her way back. She is terrified of herself, of her rage, life, the world. When she asks Jacquith in anguish if he can help her navigate “the fork in the road,” I absolutely believe her desolation, her sense of dislocation and terrifying isolation. Mother has succeeded in keeping Charlotte from becoming a “commercial traveler,” a normal person with normal social relationships, including with men.

In NV‘s third act, when a guilt-ravaged Charlotte returns to Cascade after Mother’s bitter little heart finally gives out, she finds Tina, her lover’s unwanted daughter, in residence, and we see in her what we saw in Charlotte in the opening sequence. Tina is broken by her mother’s rejection, and she is as uncertain, lost, and consumed by feelings of unworthiness and morbid fancies as Charlotte was. Charlotte recognizes herself in the kid, and she finds herself irresistibly drawn into giving Tina the love she herself was denied. It’s a beautiful impulse, the kind of healing that restores things to their proper order. By becoming a good mother to Tina, Charlotte rewrites her own story and saves Tina from the decades of wounds she suffered at Mother’s hands.

Tina (janis Wilson) as Charlotte finds her at Cascade.

But let’s talk about sex, for it is in this realm that Charlotte’s vibrant being finds expression. When Charlotte says to her first boyfriend, “I thought men didn’t like girls who were prudes,” which she admits to Jacquith she had learned from novels, she displays a frankness about her own desire that is surprising in an aristocratic Boston girl. Of course Charlotte learned whatever she knows about love and sex from books?Mother certainly wouldn’t have told her anything. But Charlotte acts throughout NV with a maturity and lack of pretense around sex.

When she is preparing to leave Cascade after her first stay, Jacquith removes and breaks her glasses. “But I feel so undressed without them,” she protests. “It’s good for you to feel that way,” he replies. He has been preparing her to live an adult life, to learn to manage the vulnerability of not just feeling but some day perhaps actually being undressed in front of a man.

“But I feel so undressed without them, says Charlotte. “It’s good for you to feel that way,” says Dr. Jacquith.

Our first glimpse of Camille Beauchamp, Charlotte’s nom de cruise, still feeling fragile but looking stunning.

Upon her return, Charlotte finds the strength to defy Mother partly because of the camellias Jerry has sent.

Charlotte’s vulnerability at first makes her standoffish when she is thrown together with Tina’s father, Jerry, her soul mate. But his gentleness and small gallantries?the way he leans in when he lights her cigarette, the bottle of perfume he gives her as thanks for helping him shop for his wife and daughters?move her deeply. When she confesses that she’s the family spinster aunt and that she’s recovering from a breakdown, he doesn’t recoil. It’s only the second time in her life she has enjoyed the attentions of an attractive man, and she is still as responsive as she was on her first cruise.

One of my favorite gowns in the movie, with its plunging neckline and Jerry’s flowers, offends Mother deeply. But Charlotte has the camellias, she can’t be cowed. She knows she is loved.

And let’s face it, a Boston Vale has to be in foreign lands to fall in love outside her class. The Vales’ Boston is a tight-knit community of old, wealthy families, and Charlotte has zero social mobility when she’s at home. But on the ship, or later in a cabin in the mountains after a car accident strands them overnight, she can be herself with Jerry in a way life as a Vale denies her at home. It’s pretty clear that Charlotte and Jerry make love that night in the mountains. Later on, when Charlotte is trying to get her dull Boston fianc? to show a little sexual interest in her, she suggests they go to some little bistro, have a few drinks, perhaps loosen their inhibitions, and he is shocked. “You must think me very depraved,” she says. Well, yes, he does. But he’s a stiff, and marrying him to prove herself normal would be suicidal.

Charlotte’s single post-Cascade clunker, the dress Mother would approve, which she wears when trying to behave conventionally.

Styling and clothes are used masterfully throughout NV to express Charlotte’s inner state. Davis’s clothes were designed by Orry-Kelly, who enjoyed an excellent working relationship with her. In this scene with Elliott, the fianc?, Charlotte wears the only unbecoming dress we see her in after her recovery?it sticks out like a sore thumb. Why, I wondered, does the dress seem so wrong? Then it struck me: Because she’s betraying herself, marrying a man Mother approves of, that’s why. The dress is a busy floral print with a high neckline?it’s a dress both Elliott and Mother would find most suitable, but it does nothing for Charlotte. It’s not her. All the other clothes she wears, which she has chosen herself, are incredibly flattering. She looks fantastic?the clothes are tailored but not severe, simple and beautifully cut?as long as she is being herself. She has almost fallen into a trap, looking for approval, doing what’s expected of her. When she tells Elliott they’d better call it a day, they are both visibly relieved. I wish Elliott luck finding a wife who won’t make any distasteful sexual demands of him. But the important thing is that Charlotte’s connection to her own erotic imagination is strong enough to steer her away from this dire marriage with a man she does not really love.

One of the things I love most about NV is that it’s a movie about an adult, written for grown-ups. When life brings Charlotte a soul mate in Jerry but traps him in a loveless marriage, they don’t ditch the kids and responsibilities and run away together. No, that’s a noir setup. Charlotte makes her failed attempt to act the part of a Boston matron, but when she realizes it’s no good she doesn’t take to drink and picking up guys at a dive bar. She makes peace with being alone, which is what you do if you don’t end up with a partner and you don’t intend to ruin your life over it. Charlotte finds a way to restore herself, help Tina, and maintain a connection with Jerry. It’s by definition a sexless solution: If Jacquith finds Charlotte and Jerry even flirting, he’ll remove Tina from Charlotte’s house. It’s a huge, improvisational compromise. Jerry characteristically fumes about taking Tina away because he doesn’t want Charlotte to sacrifice herself for his child (rather dense of him). But as Charlotte famously says at the movie’s end, “Don’t ask for the moon; we have the stars.”

Charlotte thanks Jerry for their first day together?”for a few moments when I almost felt alive.”

Jerry and Charlotte don’t ride off into the sunset, but they might live happily ever after. Sort of. Sometimes life is like that, even in the movies. In the film’s final sequence we are once again at the Vale mansion where we began, but the place is transformed. When Charlotte first returned from her cruise, she shocked her brothers by ordering a fire in the drawing room. “Mother never uses that fireplace,” they say. “High time we did, then,” she says, and we see in the final scene how Charlotte’s fire has breathed new life into the old, formerly gloomy house. Now, instead of a house that cannot breathe, presided over by an miserable matriarch who cannot stand for anyone else to be happy, is a house full of life, love, and good works.

Charlotte has also been transformed from a broken person who gets her few kicks smoking, drinking, and reading naughty books in her bedroom to a woman passionately engaged with life. Really, how much happier an ending can you ask for

Charlotte and Jerry say farewell, their time together over. But look?Charlotte is blooming. This is the only floral dress she wears that suits her, reflects her inner glow.

The final scene, back at the Vale house, Tina transformed.

Jerry: Shall we have a cigarette on it? Sure, they’re rather make love, but they’ll have to settle for a Camel….

This post was written for Cinemava’s Free for All Classic Film Blogathon. Go read the other fab posts here:

https://cinemavensessaysfromthecouch.wordpress.com/2018/01/05/the-free-for-all-blogathon/

https://cinemavensessaysfromthecouch.wordpress.com/2018/01/05/the-free-for-all-blogathon/

Indeed. We cannot ask for a happier ending. We shouldn’t.

Ain’t it the truth, Patty? That’s one of the many things I love so about NV. The ending isn’t tragic or simplemindedly happy, it’s rich, improvised, an epic compromise. I can relate.

This is an interesting, informative,entertaining analysis of the film ? makes me want to view it again with the new insights I’ve gained, especially about the costumes.

Well, thank you kindly, B. Wolf, glad you liked it!

Insightful analysis of this remarkable film. Bette Davis’ transformation is stunning in this film, but not just her physical change. That her character can become so believably self-assured and confident is inspiring and a testament to Davis’ talent.

Also, Paul Henreid has never been more handsome.

Thanks for reading it! It is an incredible performance. What a character arc! And you’re right about Henreid, he is at maximum devastating Continental charm.

I STILL need to see this movie! but It will be on TCM soon so no worries I will see it!! (That’s Why I sort of Skimmed this article- but what I read is making me really excited!!!

I hope you got to see it, but if you missed it this time, it turns up fairly frequently on TCM. It’s one of the great women’s pictures, and the more I’ve seen it the more I love it. Now *that’s what I call a classic.

An excellent analysis of an excellent film! I love Now, Voyager more and more each time I see it and reading posts like yours just reminds me how complex and rich it is. Beautiful job!

Thank you, Michaela, I feel just the same way?I never get tired of it, and it always moves me. Plus, all the performances, but especially our diva’s, and her spectacular styling, are so satisfying.

Enjoyed reading this and appreciate the precise punctuation and grammar and no misspellings. (Once an English major, always an English major.) The photos and observations on costuming seem spot on!

In the film Now, Voyager Bette Davis has two star entrances the first is we see just her unflattering oxfords then the camera slowly pulls back and then we see Charlotte for the first time. As she descended the stairs you could hear that Charlotte was being discussed. The second star entrance was when everybody is ready to disembark from the ship and everyone is standing around discussing that this passenger has hardly left her stateroom the we see a smart pair of two-tone pumps and as the camera slowly rises we then see her chic suit and finally her veiled hat.

I remember reading that Davis cooperated with Orry-Kelly when he required her to wear specially designed corsets and brassieres to mold her silhouette into the proper shape for a period role. However, when it came to wearing contemporary clothes for a film with a modern setting, Miss Davis was adamant about being unencumbered by elaborate undergarments, and her full bosom and dumpy figure presented problems. With the skill of an engineer, Orry-Kelly restructured her figure with cleverly cut, well-made garments that successfully created the desired image. In order to divert the eye away from Davis’ plumpish figure he would design these very elaborate neck designs for Davis to wear. Davis and Kelly worked well together it was when he left Warner Brothers in 1944 to open a private business, faithful to the end Bette Davis wrote that, “it was like losing my right arm.”

If your source for Orry-Kelly Designing for Miss Davis is the film “Women He’s Undressed,” you overstate the challenges. Bette Davis’ entire figure was never dumpy at the height of her career. Rather, she refused underwires for her ample bosom as she feared they could cause breast cancer. This was a specific challenge for the designer requiring skill so she did NOT look dumpy or full in the midriff.

What a great analysis of this film. Extremely well-written. I love this film.

Thank you! It’s one of my favorite Bettes, and that’s saying something. Have you read the book? It’s good, and if you’re interested in adaptation it’s definitely worth the read.