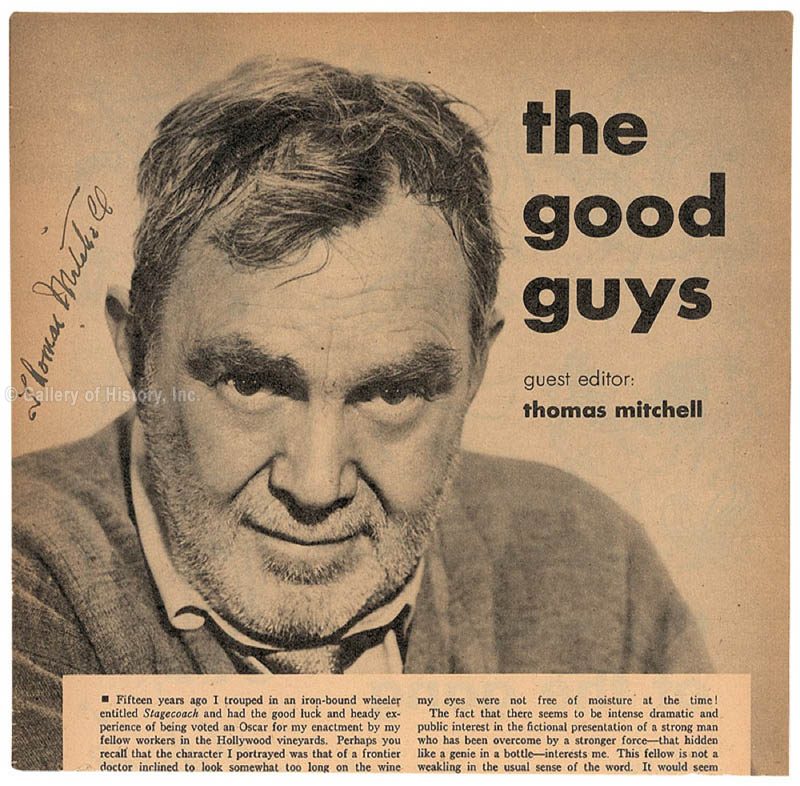

“I didn’t know I was that good” ?what you said upon accepting your Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Stagecoach (1939)

Dear Tom,

or

Dear Kid Dabb (Only Angels Have Wings, 1939)

…Diz Moore (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939)

…Doc Boone (Stagecoach, 1939)

…Clopin (Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1939)

…Gerald O’Hara (GWTW, 1939)

…and all the other unforgettable characters you wore as comfortably as an old cardigan,

For such a celebrated actor, there sure isn’t much ink on you.

I mean, researching you has been somewhat frustrating. Born in New Jersey in 1892, to Irish parents, with both your father and brother in the newspaper game, which you tried for a bit before ditching it for the theatuh. You were a Republican, apparently, though you don’t seem to have made much noise about it. You were an avid art collector. Otherwise, all I’ve found: obits, your Wiki, your entry in the Biographical Dictionary of Film, a YouTube of your appearance on a short-lived ’50s show (The Name’s the Same), a conversation with Gene Fowler in the last chapter of his book Minutes of the Last Meeting, his rumination on The Bundy Drive Gang, the hard-drinking circle of friends that included John Barrymore, W. C. Fields, John Carridine, and yes, you?though I perused the book in vain looking for you in some of the outrageous doings Fowler recalls so lovingly. These last two, along with an informative blog post at Immortal Ephemera, with your charmingly self-effacing line when you claimed your Oscar, provide about the only glimpses available of you as yourself.

The rest is your acting, and I gotta say, though I suspect you know, what both Academies (for film, and for television?the guys who present the Emmy Awards), the American Theatre Wing (who gave you your Tony in 1953, making you the first triple crown winner: Oscar, Emmy, Tony), along with directors including Howard Hawks, John Ford, George Cukor, Frank Capra, Leo McCarey, and the Who’s Who of actors you shared the screen with, know so well, so inarguably, that it’s just a fact: You were character actor royalty, one of the titans among names below the title. And you graced some of the very best movies Hollywood produced between 1937 and 1947. And while your movies aren’t all classics, a remarkable number of them are, a point demonstrated most impressively with your credit list from 1939, which includes five of that banner year’s greatest: The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Only Angels Have Wings, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Gone with the Wind, and Stagecoach. When people rhapsodize over the remarkable list of great movies from the year widely considered Hollywood’s greatest, you cut a wide swathe with some of the most memorable performances in some of the best movies ever made.

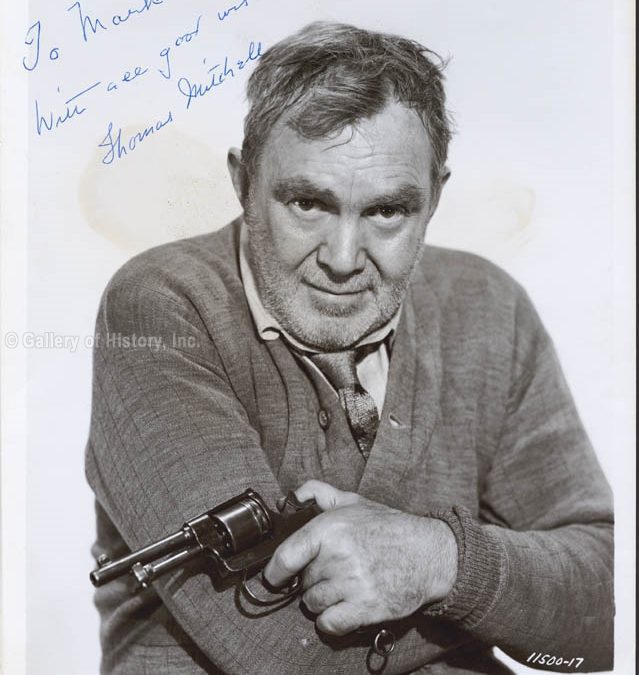

Doc Boone, cheroot clamped firmly, hanging onto the whisky sample case for dear life.

“I didn’t know I was that good” could be false modesty, but I believe it.

Your acting is unmannered and unfussy. It reminds me of what Anthony Hopkins said Katharine Hepburn told him when they were shooting The Lion in Winter?don’t act your lines, just speak them. If you know what you’re feeling and thinking, it will come through. No need to hoke it up.

After shooting Hunchback, you spoke of Laughton with great admiration. It must have been remarkable to witness him create that heartrending role by, per Laughton biographer Simon Callow, intensifying his own physical and mental suffering almost beyond endurance. Your own approach to acting appears radically different, or at least it produced a strikingly different effect. How did you work, Tom? How did you speak so simply and clearly from inside all those disparate characters, as if you were just being yourself?

Or maybe it’s all an act, and you’re just a common actor, mostly ego and vanity. You could pull it off. I’ve been rewatching some of your movies recently?specifically the five 1939 blockbusters, and I failed to find a single instant when you blink, when your mask slips.

Great acting is so mysterious, to me at least. To you, it’s probably not. Talent looks mysterious to those who ain’t got it. Maybe to you, the process of fully becoming someone else, someone whose presence has a totally different quality from your own, is a process of the most prosaic sort.

All I know is, it was so interesting to see you on The Name’s the Same, in 1954. In that few minutes, in which Robert Q. Lewis leads a panel including Arnold Stang and former Miss America Bess Myerson as they try to guess what you would like to do. They fail, because your wish was “to do nothing.” Watching you answer their questions, amiably and intelligently, gave me even more respect for the transformation you effect when you act, because your entire presence as Tom Mitchell was so very different from any of your roles.

You memorably played drunks, at least two of them doctors (in The Hurricane and Stagecoach), and your membership in good standing in the Bundy Drive Gang suggests that you at least enjoyed the company of hard drinkers, which almost certainly means you could enjoy the occasional binge yourself. But it would fall upon you to regale me with your misadventures in that celebrated liver-destroying brotherhood, because your own personal life is a black box?no arrests, no fights, none of the chaos or medical problems that mark the lives of alcoholic movie folk, who often ended up in the newspapers despite the best attempts of the studios’ publicity departments.

But watching you as Doc Boone in Stagecoach, happily and methodically drinking your way through Mr. Peacock the whisky drummer’s sample case as he repeatedly tries, ineffectually, to reclaim it, then your expression and kindly response when you are rebuked for smoking and sickening the pregnant Mrs. Mallory…. You play Boone’s drinking for laughs, as was the custom of the era, but Doc Boone is hardly a clown. He is an iconoclast, a reproach to convention and the judgment and rejection of the respectable. He’s sort of a conduit between the respectable and shady characters. Doc is unapologetically self-destructive and committed to drinking, but we see nothing morbid about it. He’s not killing himself out of some poorly concealed self-loathing. He is, he cheerfully tells his traveling companions, a fatalist, and he knows eventually some bullet or bottle will have his name on it. Being a Civil War veteran, he long ago faced his mortality. Doc Boone is philosophical; he rejects society’s judgment of him as a drunken failure, and when Mrs. Mallory goes into labor, he pulls himself together and ?delivers her baby. This gives him evident satisfaction, and he immediately rewards himself. With a drink.

As Doc Boone, you are the most self-aware of the stagecoach’s passengers. In Stagecoach, respectability is window dressing for hypocrisy or, in one character’s case, outright criminality. The banker/embezzler, Gatewood, is a dreadful blowhard, bloviating his obnoxious grievances at top volume, too wrapped up in his tirade to see how his shouting is increasing Mrs. Mallory’s distress. Gatewood is perpetually outraged, always feels hard done by. He berates their army escort for following orders and leaving to deal with Apache attacks, and treats Dallas, the prostitute (Claire Trevor), as though she is beneath contempt (note: Gatewood’s wife is the leader of the citizens’ committee that forced Dallas and Doc Boone out of town). A couple of the other passengers treat Dallas like dirt, too. But we know Gatewood is a crook who hides behind his position, and that his wife’s civic group supports the cruelty of respectable society.

In a 1921 production of Synge’s Playboy of the Western World

When Dallas falls in love with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne, sigh), it’s you she turns to for advice. There’s something about you that makes you that guy, the one women trust with their most delicate problems. Jean Arthur confides in you in both Only Angels Have Wings and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. In the first, she starts out as your competitor for Cary Grant’s attention but you end up becoming allies who both love him, and in the second, you’re in love with her, but when she falls for her un-wised-up boss, you support her all the way.

You often play deeply flawed characters, but you never reduce them to their flaws. I’m increasingly aware of a shared quality among some of my favorite actors: humanism. You give us whole human beings, messy but with some divine spark of inner life. We rarely know their backstory, but you somehow offer these characters to us without obscuring either their weaknesses or their beautiful qualities?courage, intelligence, kindness, compassion. Even in weakness or downright impotence, they often see underlying, painful realities that elude most of us. Seeing the truth can be a terrible burden, and it’s possible that Doc Boone and Dr. Kersaint, in The Hurricane, may drink partly to lighten that burden.

I don’t care about space travel, but time travel is something else?that I would do in a heartbeat, given a guaranteed safe return to my own time. Watching old movies is my preferred form of time travel. But alas, I cannot make my way back to Broadway to see you onstage. If I could, I’d buy a ticket to see you as Willy Loman in the 1949 national touring company of Death of a Salesman, in which you replaced Lee J. Cobb. What would you do with such an unsympathetic character? How did your compassion express itself in Willy? I just found your performance (audio only), along with Mildred Dunnock and Arthur Kennedy and the rest of the original cast, at the Internet Archive. So at least I’ve now heard your Loman, as close as I’ll ever get to seeing you in a play.

Shortly before you left us in 1962, you premiered the character Columbo onstage. Of course a few years later, Peter Falk would make Columbo his signature TV role. I’d love to see your version, though. And I’d love to see you in Hazel Flagg, the 1953 Broadway musical version of Nothing Sacred, William Wellman’s 1937 comedy. It would be wonderful to travel even further back, to 1913, to see you learning your craft as a young actor in Charles Coburn’s Shakespearean troupe. And also the plays you wrote, and it would be fascinating to see you direct.

In his Tony-winning turn in Hazel Flagg (1953), Jule Styne’s adaptation of Nothing Sacred (1937)

If we could sit down for a couple of cocktails, and you felt comfortable talking about personal stuff, I’d love to hear about your marriages?the two long ones to the same woman, Susan, separated by a rather brief one after the first divorce. She and your only child, daughter Anne M. Lange, were at your side when you left this world at your Beverly Hills home from cancer, aged 70, just two days after Laughton had succumbed to the same disease. I’d like to hear about your farm in Oregon, the one you described when you visited a Washington state navy hospital in 1944 (from the hospital’s newspaper, also at the Internet Archive). That article says you were best friends with Laughton. Is that true?

And I would say, as I signaled the bartender for two more of the same, You’re a writer. How come you didn’t write a memoir? Your career has been so interesting, and 56 years after your death, thanks to TCM, we’re still loving your work. You were a witness and participant in a huge chunk of Hollywood history, not to mention your long career on the stage and a shorter but vibrant one in television?but there is no full-length biography. And it’s your voice I want to hear.

I want to read your thoughts and observations. Not just about yourself, but all the people you worked with, your experiences making the films (my favorite!), and whatever of your personal life you felt comfortable sharing. How did you end up married three times, for a scant two years, sandwiched between two 20-year marriages to Susan, who was with you when you passed?

You wrote plays and screenplays, so you certainly could have written a memoir, and I bet it would have been a doozy. Oh, the stories you could tell, about making some of the most beloved movies of all time. Your recollections of Laughton, Cary Grant, Vivien Leigh, Jimmy Stewart, Maureen O’Hara, Jean Arthur, Claude Rains, John Wayne, Gregg Toland, Beulah Bondi, Fay Bainter?oh yes, another doctor in your gallery is Doc Gibbs in Our Town (1940), with Bainter as Mrs. Gibbs. And the tales of your early career with Coburn’s Shakespeare company, and your stories of the Bundy Drive Gang….

As Diz Moore in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, showing up wet-behind-the-ears Senator Jeff Smith

Were you just so busy, what with movies, theater, and television, that you could luxuriate in a fantasy (“doing nothing”) that most actors could only envy? Maybe as a writer you knew how much work it would be, how much of your time it would consume, and it was only worth doing if you did it right. And maybe you preferred to let your work speak for you.

Seriously, Tom, why didn’t you write a memoir?

You gaze for a moment into your glass, that little smile playing across your face, that familiar mischievous glint in your eye, then you say you’re just an actor, and living life is so much more interesting than writing about it. Then you take a sip and start telling me about your art collection. And I am riveted.

This post was written for the 2018 edition of the What a Character! blogathon, hosted by Once Upon a Screen, Outspoken and Freckled, and Paula’s Cinema Club. There’s lots of great posts, so get on over and start reading.

I loved your letter to Tom. You spoke from the heart for yourself, and for so many of us.

He gave us his best in presenting the good, the mundane, the glorious and, sometimes, the evil in humanity. We are better for watching a Thomas Mitchell performance.

Thank you, Patty, that means a lot coming from one of my favorite bloggers.

This is absolutely fantastic. You?ve written a brilliant piece here! I wish Mr. Mitchell could read this. I wonder if he?d be surprised at how he affected you, us. Everything you wrote articulates feelsings I did t know I had for him. Bravo! I love this.

Thank you so much, Sarah!

Every year, I watch “It’s a Wonderful Life” on the big screen and weep a little at the end. Yesterday was my annual screening, and I paid close attention to Thomas Mitchell, noting he never allows us to despise his character.

Like you said, his acting is never fussy or overwrought. He always convinces me that he IS his character.

I agree his memoirs would have been fabulous had he written/published them. The stories!

Thank you for this marvellous tribute. Like Caftan Woman said in her comment, you wrote from the heart, and you wrote from mine, too.

Thank you kindly, so glad you enjoyed it.

I envy you seeing IAWL on a big screen every year! I would be there in a heartbeat.

It really was from the heart. I know that for you and me and the rest of the classic movie blogging community, these artists and our love for them is serious and very personal. I’m hoping to write more pieces in this Love Letters format. It allows me to explore that powerful sense of personal connection and ask the questions I would if I had a couple of hours to hang out with these intriguing people, who contributed so much to our rich movie legacy.

Lesley, I am speechless, and clapping in front of the computer. Your letter was fabulous, and if it could be delivrered to Heaven, Thomas would be incredibly moved by it.

I didn’t know he was the very first Triple Crown winner – only one of the things your letter taught me. Unfortunately he didn’t write a memoir, but I believe you would be the perfect person to write his biography.

Kisses!

Thank you, Le, for your kind remarks, glad you liked it!

This is absolutely beautiful. Thanks for such a thoughtful letter to one of my favorite character actors. You pinpointed some things about him that have never occurred to me before but which make me love him all the more.

You are very welcome. It was such a pleasure to spend time with Mitchell, seriously considering him rather than just enjoying him but taking his reliable excellence for granted.