Martha Ivers in the shadows

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers?is a total kinkfest, and if you?re new to it, you can use a little help learning the ropes. I?ll be happy to show you around.

Time Out?s synopsis is as concise and elegant as could be, so here it is:

?Superb performance by Stanwyck?as the apex of a traumatic triangle comprising the two men who (maybe) saw her club her wealthy aunt to death when they were children. Now a tycoon in her own right, bonded to one of the witnesses (Douglas) in a guilt-ridden marriage, she finds the other (Heflin, raaaaar!*) resurfacing in her life as both promise of escape and threat to her security?and the stagnent waters begin to stir again with murderous cross-currents of fear and desire. A gripping film noir, all the more effective for being staged by [director Lewis] Milestone as a steamy romantic melodrama.?

1?The?Strange Love of Martha Ivers?is a noir?no, it?s a melodrama?no, it?s a noir!

STOP!, You?re both right!

Noir isn?t genre-specific?there are noir westerns, noir romances, noir women?s pictures. I think sometimes people are confused by these layers or hybrid genres, and movies can be misclassified and not get the attention or analysis they deserve.

I have several anthologies of writings on noir, and not a single one has a single sentence about this movie. Which is strange, because it?s full of noir-y goodness.

A killer and her alibi: Martha and Walter as kids

One of the great things about noir as a style is its flexibility. There are a lot of elements in noir in terms of narrative and visual style, and these elements occur in different combinations.

Here?s a checklist for?TSLOMI:

femme fatale, check

crime (usually murder), check

a corrupt ?noir city? locale, a city on the make where morals are loose, debased, or corroded beyond recognition and ethics are a luxury: check, check and check

characters bound together by desire (for sex, money, power, or love, or any combination of these) and guilt

moody, Expressionistic black-and-white cinematography with oppressive shadows and angles

2?Stanwyck?s performance: Bet neither?Double Indemnity?s Phyllis Diedrickson nor Martha Ivers knew she had an identical twin as evil as herself,?but these two?femmes fatale?are sisters under the skin.

They?re both mercenary. They both use sex to enlist confederates in their schemes. And they?re both turned on by killing and have a secret crush on death.

Martha?s sister under the skin, Phyllis Diedrickson, from Double Indemnity. Phyllis doesn?t pretend to class?she?s a tramp, end of story.

One difference is that while Phyllis looks as cheap as she is, Martha Ivers is exquisitely turned out (Edith Head?s costumes couldn?t be more flattering or make Martha more chic and desirable). Phyllis?s peroxide-blonde mane is a definite statement coif leaving no doubt that she?s on the make?hell, she?s advertising. Whereas Martha gets around, too, but flirts in a different register.

Another difference is that while Phyllis admits that she?s never loved anybody, Martha believes she has always loved Sam. Sam almost believes her, but he finds out the truth, to his dismay. ?Your whole life has been a dream,? he tells her.

Stanwyck?s range is part of what makes her one of my Holy Trinity of screen divas (with Davis and Crawford in the other spots), but so is her willingness to play the most awful characters with 100 percent commitment, never worrying about whether or not she?s likable. Fred MacMurray understandably swore off playing bad guys after his fans reacted with shock and anger at his incredible portrayal of Jeff Sheldrake,?The Apartment?s cad, philanderer, and office blackmailer, sticking after that to affable?guys, Disney guys,?My Three Sons?guys. I don?t blame him, but I do give props to Stanwyck for her embrace of characters?that are radically unsympathetic. It shows a real commitment to acting, to digging into the depths of human behavior, rather than protecting her star image by staying on the likable side of the street.

Both Martha and Phyllis have murdered, though at least Martha?s first murder was a crime of passion, while Phyllis only goes in for carefully plotted murder-for-profit.

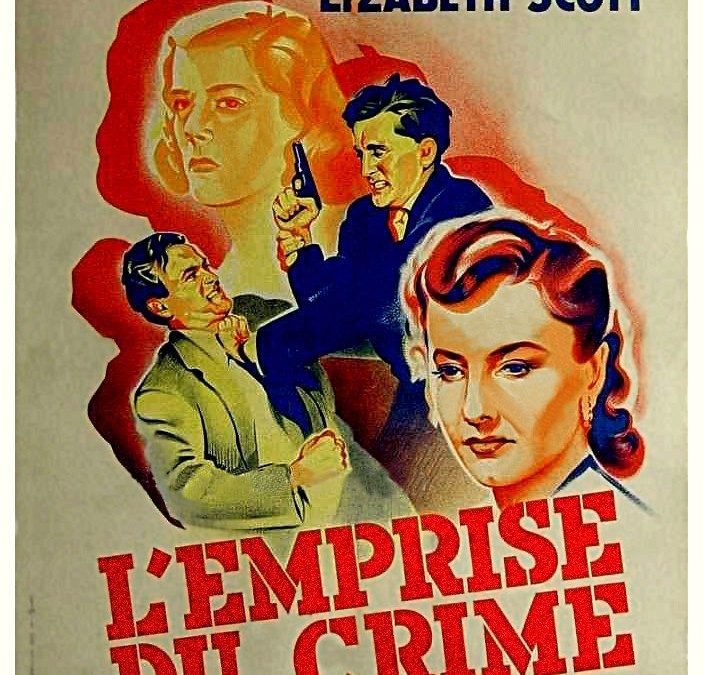

3?Interlocked triangles, a lesson in the human geometry of desire:?SLOMI?has not one but two triangles, with Martha and Sam (Van Heflin) in both. In Triangle One, Martha is the pivot between Sam and Walter (Kirk Douglas in his sizzling screen debut), and in Triangle Two, Sam is the pivot between Martha and Toni (Lizabeth Scott in her sophomore film appearance), the gorgeous, emotionally bruised ex-con Sam meets on the steps of the house he grew up in.

I can?t think of another movie with this interlocking triangle schema, and it generates a lot of heat?and tension. Course you have to believe the outcome is not forgone, that we can?t tell for sure which way things are going to swing, who?s going to end up together and who?s going to end up alone. This is maybe the trickiest part of the script and direction, and it mostly succeeds due to a careful set-up.

The Martha-Sam-Walter triangle is established right?up front in the movie?s opening scenes, as is the dynamic between the three. Martha always preferred independent, resourceful Sam, from the wrong side of the tracks (like her late father), and Daddy?s boy Walter always pined for Martha and nurtured a poisonous envy of Sam.

?

Sam (Van Heflin) and Martha (Barbara Stanwyck) embrace while Martha?s husband Walter (Kirk Douglas) looks warily in a scene from the film ?The Strange Love Of Martha Ivers?, 1946. (Photo by Paramount Pictures/Getty Images)

?

The second triangle: Sam, Toni, and Martha, who has the home team advantage?she owns the hotel.

?4?Welcome to Iverstown, a proud Noir City: Iverstown is one of those American cities that exemplifies noir values. Factory-owner Martha runs Iverstown as her aunt did before her, though Martha has?D.A. husband Walter to manage her enforcement squad, cops on the make eager to please her. There doesn?t even seem to be a city government, though there must be a figurehead mayor to pursue Marsha?s political agenda. Noir cities can be real cities like New York, L.A., San Francisco, or made up cities in unspecified states, like Phenix City, Potterstown (yes, there?s a persuasive case to be made for?It?s a Wonderful Life?as a noir), the unnamed city in?Asphalt Jungle, and of course Iverstown.

Can Sam and Toni navigate the crooked streets of Iverstown? And if they escape, what are their chances of finding happiness?

Iverstown is the kind of place where Martha can phone up the garage where you?ve left your car to be repaired and make sure it won?t get done before she?s ready to let you go. It?s also the kind of place where Walter can blackmail Toni into making a deal to set up Sam for a beat-down to scare him out of town in exchange for not sending her back up for a minor parole violation.

It?s a take on life in America that developed toward the end of World War II and fully flowered at the war?s end, when returning servicemen came home to a nation that seemed not quite the same as the one they had left. The country had changed, and the war had changed them.

Sam is a veteran. Martha reminds him that?he?s killed before, but he tells her that was different?that was in the war. ?I?ve never murdered,? he says, raining on her dreams of his proving?his love for her by knocking off?her guilt-ravaged alcoholic husband, a stone around her neck.

5?Who made this movie, and how did it get this way? It was produced by Hal Wallis after he left Warner Bros because he didn?t have enough autonomy. The credited director is Lewis Milestone, best remembered for?All Quiet on the Western Front?(1930), which won him a Best Directing Oscar and also received the Best Picture Oscar. But a strike during production of?TSLOMI?kept Milestone off the set and in his absence, veteran director Byron Haskin, who was one of Milestone?s assistants, served as director. I don?t know if we know who shot what or how much Haskin contributed to the final cut, but the film?s assured noir direction is rather surprising in terms of Milestone?s other directing credits. One startling moment could have been directed by either man but seems to harken back to both of their background in silent film: the moment of the murder. It?s shown with great economy and even great drama, Martha seizing and raising high the poker, Anderson cringing and dropping under the blow.

?

Director Lewis Milestone with three of Strange Love of? stars

?5?Other studio craftsmen who contributed to the film?s look and mood: Composer Miklos Rozsa, whose wildly romantic score contributes to the generally overwrought, neurotic quality; Edith Head, whose costumes for Stanwyck are fabulous and exactly right and whose clothes for Toni are just a little too well-cut for a down-on-her-luck gal; and veteran cinematographer Victor Milner, who shot 132 feature films between 1918 and 1953, mostly at Paramount, including several for both Preston Sturges and Ernst Lubitsch as well as?It?s a Wonderful Life?and the noir?Dark City.

?

?

?7?Supporting cast: Two impressive character actors, Roman Bohnen (Dana Andrews?s father in The Best Years of Our Lives) and Judith Anderson, add their skills to the ensemble. Bohnen is Walter?s scheming, greedy father, and Anderson is Martha?s archenemy, the wealthy aunt who wants to purge her father from Martha to prepare her for a life of power and privilege.

Walter?s father (Roman Bohnen) and Martha?s aunt (Judith Anderson)

?

8?Martha?s always been turned on by the tawdry. In the first scene, when she and Sam are kids, running away, and he brings her food, she says hopefully, ?Did you steal it?? And when she visits Sam in his cheap hotel room, she is totally turned on by the place. She happens to own the hotel but has apparently never been there before, and she?s almost romantic about it.

Martha (Janis Wilson) and Sam (Daryl Hickman), running away. Martha asks conspiratorially if Sam stole the food; No, he says, ?and don?t go making up any stories about that if we get caught. I?m already in enough trouble??

Here?s another difference between Phyllis and Martha: Phyllis wanted to move up, to get her hands on a lot of money. Martha has a lot of money, and what she has always wanted is to get back to who she started out as?Martha Smith, a factory hand?s daughter. At least that?s the dream she?s lived in, the desire she believed she was serving.

The reality is something different, and if the script doesn?t quite tell us what her real desire is, Stanwyck convinces us that both desires, the one she believes and the underlying one, have steered her off a cliff. When her dream collapses, Martha has nothing real to hold onto, and her husband finally gets her to himself.

Trivia: The sailor-hitchhiker who sleeps through Sam?s car accident is Blake Edwards, future director.

*Love me some Van Heflin.

This post was written for the Remembering Barbara Stanwyck blogathon, hosted by?Crystal?at?In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood. Head on over and check out the other posts?you?ll be glad you did!

Fantastic actress – starred in two of the best films I have ever seen – esp. Double Indemnity. Intelligent, beautiful and interesting.

And, as far as I am concerned, the most beautiful actress of her generation.

Just watched this remarkable film and found your brilliant comments on it iluminating and insightful. What a picture!

Thank you kindly, it still strikes me every time I watch it what an odd duck it is, and how perverse and fascinating.

This was the film I saw as a teen on a Sunday morning with my parents. From the moment, Stawyck stepped from the car, she mesmerized me for life as my favorite actress. Loved your analysis!

Thank you kindly, Thomas, this one has a special place in my heart. Stanwyck never looked better, and she brings the perversity the role demands. The whole movie’s awash in it, and it’s glorious.