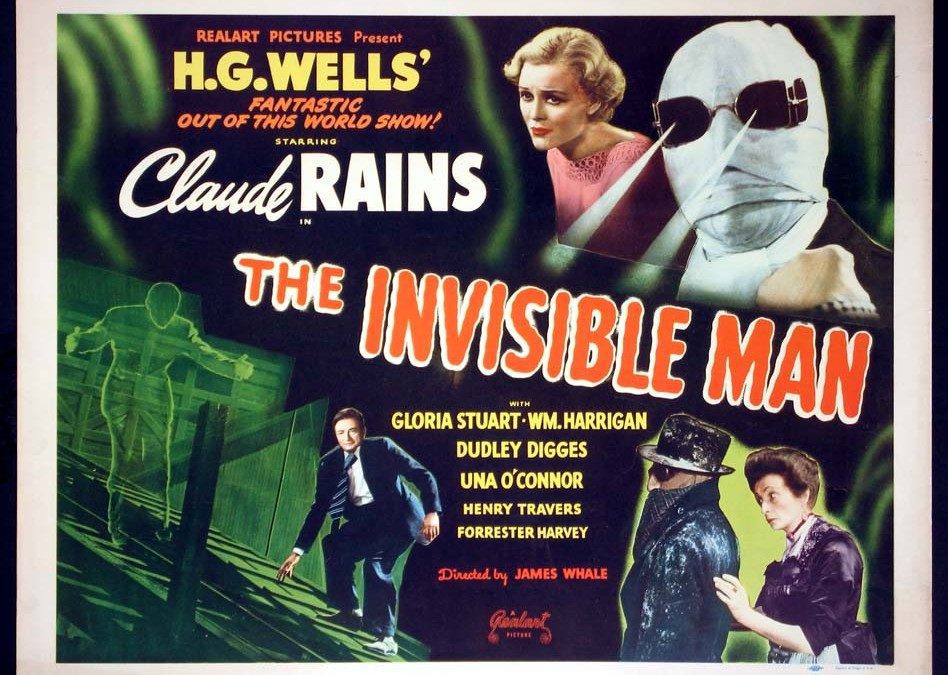

The Invisible Man?is a bit of a?stepchild among James Whale?s Universal horror films, which is understandable since?Frankenstein?(1931) and even more?Bride of Frankenstein?(1935) were not just sensationally successful at the box office but embedded themselves into popular culture where they remain more than 80 years later. (Here?s?my post?on?Bride of Frankenstein.)?The Invisible Man?has left its mark as well, which is particularly impressive since it lacks Karloff?s lyrical, yearning monster, whose extraordinary appearance permanently imprints itself on viewers instantly.?The Invisible Manis notable for many reasons, one of the most striking that its title character?s face is not?actually seen until the movie?s final?shot. Claude Rains is in almost every scene of the 71-minute film, but he has to carry it solely with his remarkable voice?that and the special effects that fool us into feeling that there really?is?an invisible man in the room? Here?s some info that will enhance your pleasure and appreciation of the movie.

1?Claude Rains?s voice:?Rains had been born in poverty in London, his father an actor of ever-shifting?fortunes. Rains first appeared onstage at the age of 11. The founder of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where Rains would later teach, paid for elocution lessons for the boy, who was from the first extremely ambitious and diligent. Rains?served in World War I and was injured?in a?poison gas attack, as a result of which he temporarily lost his voice, and when it returned it had a new thickness and distinctive grain. He also lost most of the sight in one eye, and that never returned. Rains?s voice is one of the most easily identifable in cinema, and it?s hard to believe he began life with a thick Cockney accent and speech impediment (he had trouble finding his Rs). He practiced?vocal exercises assiduously and succeeded so completely that it?s hard to imagine that his voice ever marked him as working-class, that it was ever different from the one we know?powerful, gruff, expressive, supple. An actor?s voice, though, isn?t worth much unless the actor can act, and Rains?s talent brought him stage stardom first in London, then at the Theatre Guild in New York.

The first reveal of Griffin?s invisibility, about seven minutes into the film.

2?The story:?Universal purchased the rights to H.G. Wells?s 1897 novel ior $10,000 in September, 1931. Over the next year and a half, several directors and a gaggle of writers including John Huston and Preston Sturges turned out treatments or drafts. Even Whale turned in a six-page treatment at one point. The stories were all over the place: Sturges?s sent the Invisible Man to Russia to avenge his family?s?murder during the Revolution; R.C. Sherriff claimed?in his memoir that another version made him a space alien who wanted to fill the Earth with invisible alien armies. Whale finally turned to Sherriff, the playwright/screenwriter whose play?Journey?s End?had been Whale?s first major success. Sherriff dug through the big pile of versions, finding little of use, and finally went back to Wells?s novel. He wrote a screenplay that hewed closely to it, adding dialogue and characters to punch up the drama, and he also grounded the fantastic tale in the ordinary and everyday, understanding that audiences have an easier time following you into fantasy if they can first connect to something familiar. Finally?Whale, Wells (who had script approval), and the Hays Office approved it.

3?Jack Griffin, mad scientist. In good-scientist movies, the protagonists?are driven by a?desire to eradicate disease or to serve mankind (Twilight Zone?ref!). Mad scientists are driven by a lust for power, whether to unlock the secrets of life (whatever that means) or to rule the world. When?The Invisible Man?starts, Jack Griffin is already invisible?and?mad?the latter?a side effect of the drug that erased him. But even before his terrible breakthrough Jack?s motives were not so hot. He had dreamed of being the most important scientist, of?discovering something that would make him wealthy so he could impress his fianc?e, Flora, by buying her jewels and furs. In other words, Jack started out with a massive shot of grandiosity, and the monocaine?the drug Sherriff made up for the script?just took Griffin?s?original character flaw?and amplified?it in the nastiest way. Griffin beats a policeman to death, wrecks a train, and sends Kemp, the colleague who has betrayed him, over a cliff in his car, which crashes and burns. And he was just getting warmed up.

?

Holed up at the Lion?s Head, searching for an antidote.

4?Claude Rains?s introduction to the movies:?Whale was astonished to find that Rains had only seen a handful of movies, and assigned him to see as many as possible right away. Shooting?TIM?was to be if not a baptism by fire a baptism by black velvet. Sherriff?s script had called for Griffin?s clothing to be moved through the scenes on wires, marionette-style, but Whale rightly pointed out that the clothes would obviously be empty and that viewers needed to really believe Griffin was there even though we can?t?see him. This involved an arduous process in which all of Griffin?s scenes were shot multiple times. The first time they were shot with the other characters on the set. The second time, the entire set was covered in black velvet, floors, walls, and ceiling. Rains was also completely covered in black velvet, over which he wore Griffin?s clothes. Imagine how hot it was under the lights in those layers of thick material, with even his mouth covered. His hearing was so muffled he could only get direction via megaphone, and more than once he fainted from the heat.

Rains later described how ghastly it had been for him, traumatized by his war experiences, claustrophobic, to do the film. Apparently Rains was sometimes doubled in the black velvet scenes. In addition there was the really traumatic posing for the plaster mask that would be used in the final shots, after Griffin has died, to show him returning to visibility. Rains?s face was covered with plaster and he could not move; straws were inserted in his nose so that he could breathe while it hardened. I don?t know about you, but I feel a little panicky?just thinking about that.

5?James Whale?s direction:?Whale creates a sense of place in the movie?s opening scene, borrowed from his own Black Country childhood. The Lion?s Head Inn, where Griffin seeks shelter and a safe place to work on?an antidote, is heavy with atmosphere. Whale agreed with writer Sherriff about grounding a strange tale in ordinary experience, and that?s what he did. In addition, Whale kept in mind stories from his childhood about ?pub ghosts? who break glasses, knock things over, and otherwise make mischief that cannot be explained. Also, Whale?s interest in all aspects of production may have been unusual in the studio system, but it did give the films in which he had full creative control a kind of unity of vision that was unusual in the era.

6?Supporting cast?Henry Travers, Una O?Connor, Dudley Digges, and Gloria Stuart. Whale filled his films with memorable character actors like Travers, O?Connor, and Digges, and he had previously worked with Stuart, who plays Griffin?s fianc?e, Flora, on?The Old Dark House?(1932). Walter Brennan and John Carradine (then billed as Peter Richmond) have cameos, and Dwight Frye, famous as Renfield in?Dracula?and Fritz?in?Frankenstein, has an uncharacteristically normal bit as a newspaper reporter at a police press conference.

The Invisible Man Returns poster

7?The monster that Griffin creates is himself:?Dr.?Frankenstein?s monster was stitched together from?corpses; Jack Griffin experimented on himself, and when things went bad there was no escape. That?s the real horror of?The Invisible Man?Griffin?s contempt for life and humanity is played out in his own ruin. Dr. Frankenstein and his bride could (in theory) escape the castle before the monster destroys it in?Bride of Frankenstein, but Griffin?s only hope was to find an antidote, to restore himself. Failing that, he is trapped not only by the police but by his own madness and failure.

8?Before and after:?Whale?s?TIM?was not even close to the first movie about invisibility. According to Rudy Behlmer?s DVD commentary track, that came in 1904, only seven years after Wells?s novel: It was a French film,?Invisible Sylvia, which was followed in 1905 by?The Invisible Thief. Biograph?s?The Invisible Fluid?made both people and objects invisible. In 1910 came a British film,?The Invisible Dog.?The Unseen?(1914) features an invisible scientist. A 1923 feature directed by Roland West,?The Unknown Purple, has an inventor discover a purple light that ?renders the user invisible. He uses the light to revenge himself against those who framed him for theft.? Also in 1933, the same year as?TIM, came a German film,?The Invisible Man Goes Through the City. There were?cartoons, too, like a 1939 Looney Tunes,?Porky?s Movie Mystery,?with Porky as Mr. Motto (not Moto), trying to track down the invisible man who is creating havoc?at the film studio. The guy turns out to be a caricature of comedian Hugh Herbert. Behlmer says that before and after?TIM?there were various features, serials, TV versions, even commercials.

?

?

from Porky?s Movie Mystery, a 1939 Looney Tunes starring Porky as Mr. Motto (no typo)

The Invisible Man?was a huge hit with critics and audiences, and for the first time since?Frankensteinhad put Universal in the black two years before, it was back in the black again in this darkest year of the Depression, when movie attendance had fallen by as much as 60 percent. Whale?s version spawned sequels, among them?The Invisible Man Returns, The Invisible Woman,?and?Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man. The special effects pioneered by Whale and Co. for?TIM?are remarkably similar to those used by Hal Roach a few years later for his?Topper?films, and again on television 30 years after?TIM?s original release for?Bewitched?and?I Dream of Jeannie, among others.

9?Despite the horrors of filming?The Invisible Man, Rains?s professional discipline carried him through, and at the age of 44 he had a new career on the screen. He was nominated for Academy Awards for?Mr. Smith Goes to Washington?(1939),?Casablanca?(1942),?Mr. Skeffington?(1944), and?Notorious?(1946), but never received an Oscar, which in my humble opinion ranks with the greatest Oscar snubs ever. Rains continued to work in films until 1965, two years before his death at age 77. He never stopped hating Hollywood, always leaving immediately after completing a project and hightailing it?back to his beloved farm in West Bradford Township, Pennsylvania.

9?The loneliness of the invisible mad scientist:?Wells?s?Invisible Man?was mad before he became invisible; it was Hollywood that made the madness a side effect of the invisibility drug. Wells?s scientist just disappears, unable to find an antidote to return him to visibility. It?s horrifying if not particularly cinematic. But despite Griffin?s violent insanity getting all the attention, his loneliness is still very real, and he mentions it in a couple of quieter moments. Once again Whale had made a movie about a monster, this one human, who is cut off from even the people he loves. That?s the vein that underlies everything else?the effects, the humor, the artistic settings and vivid performances (almost exclusively; there is one policeman whose single-line reading is so wooden I wonder if he might have been one of Whale?s partner David Lewis?s relatives, whom Whale got extra work whenever he could), and it is that melancholy that provides the emotional palette for the whole film. It?s not?Bride of Frankenstein, which is one of the greatest films ever made in Hollywood, but?The Invisible Man?is still prime Whale, and that is saying a lot. It?s worth a first or second or third look, and its qualities are anything but invisible.

This was written for the?Movie Scientist Blogathon?sponsored by Christina Wehner and Silver Screenings. There are excellent entries on good, mad, and lonely scientists?go read them right now!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks