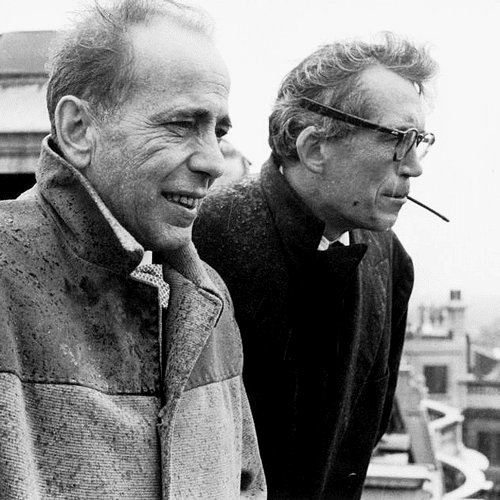

On the set of The African Queen (1951)

John Huston and Humphrey Bogart made six movies together, six points of intersection over their long careers. Three of the six were crucial in the careers of both men:?The Maltese Falcon?(1941),?The Treasure of the Sierra Madre?(1948), and?The African Queen?(1951).

Actually, they?made a seventh film together?High Sierra?(1941)?which Huston wrote and Raoul Walsh directed. But it was Huston?s depiction of Roy Earle that finally nudged Bogart over the line from character actor in As and star in Bs to the top echelon of stars in Hollywood.

In High Sierra (1941), with Ida Lupino, whose top billing reflected Bogart?s not-quite-a-star status, and Pard the badluck pooch, who gets his own credit (?played by Zero?)

Both men were drinkers and raconteurs, Hollywood ?bad boys.? Both were ?cheerful anarchists? who sympathized with issues of social justice and who faced (as did many others, but they were among the most prominent) scrutiny and threat by HUAC and Red Channels. Both hated fakery and phoniness with every fiber of their being. Both were to-the-bone iconoclasts who distrusted authority. Both took time to settle down and find their metier as filmmakers but eventually found lasting success. And both took little in life except their work seriously.

On the other hand, there were strong differences. While Huston had always been an adventurer and globetrotter who loved spending time in the wild, hunting, unbothered by rough conditions, Bogart was strictly an urban tough guy, and his obsession with sailing was his only nod to the sporting life. Still, though he loathed travel Bogart twice allowed Huston to drag him into the wild to make movies (Treasure?and?African Queen), an indication of how much he trusted his friend and director.

The Bogarts leading the CFA in Washington, D.C., lending short-lived support to what would come to be known as the Hollywood 10. Paul Henreid, behind Bacall, never forgave Bogart for reversing his stand. But Huston?s and Bogart?s relationship would endure.

Another difference was how the two men dealt with the threat of blacklisting during the HUAC witch hunts. They started out on the same side, as members of the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA), standing with prominent film stars such as Gene Kelly, Danny Kaye, Edward G. Robinson, Myrna Loy, Paulette Goddard, Groucho Marx, and many others in decrying the whole enterprise as an assault on fundamental democratic freedoms and ethics. Huston, the Bogarts, and other representatives of the CFA flew to Washington, D.C., to stand in solidarity with the Unfriendly 19 (of whom Billy Wilder said ?Only two have talent. The other 17 are just unfriendly?). On the way east the flight made several stops and was greeted by friendly reporters at each. But the proceedings in D.C. turned things around instantly?Huston was sickened by the grandstanding of those being questioned but remained steadfast in his opposition to the committee?s goals and methods. Bogart felt betrayed by some he had been defending who turned out to have been party members in the past but had not admitted it straight out when the trouble started.

More on?this later?

Bogart was seven years older than Huston (1899; 1906). Both came from privileged backgrounds, Bogart the son of a prominent Manhattan physician and Huston the son of actor Walter and Rhea Gore, a journalist. Bogart?s childhood was as conventional and comfortable as Huston?s was unconventional and peripatetic. Bogart attended prep schools in Manhattan, and, like Huston, was as a student indifferent at best. After Huston?s parents separated he split his time between them, at the elegant hotels and racetracks his mother frequented and at rehearsals and performances as well as the far less luxurious theatrical boarding houses where his father, not yet a star, lived.

Baby Bogart

Huston traveled between his parents? worlds with ease, and what he was exposed to as a child defined his interests and sensibility as an adult pretty thoroughly. From Walter and hanging around in vaudeville houses and theaters he got his familiarity with the world of the theater, and from Rhea his love of literature, luxury, adventure, and gambling.

Walter and John Huston, 1930. John still has his baby fat?he looks unsure of himself, without the effortless authority of his more mature photos.

In 1924, after decades toiling in the theater, Walter Huston finally achieved stardom in the New York production of?Desire Under the Elms,?with John attending and closely observing the rehearsals. He said that those few weeks gave him the foundation for his career as a director. When Walter went to Hollywood in the early sound era his son followed, signing a six month contract as a scenarist.

His first film was?A House Divided, in which his father starred. It was directed by William Wyler, who was to become JH?s friend, mentor, and champion.

Bogart also first came to Hollywood in the early sound era, but his first film appearances didn?t exactly light the world on fire. For the next few years he was effectively bicoastal, doing stage work in New York and movies in Hollywood. It?s odd, knowing Bogart as we do, to discover that for more than a decade one of the quintessential tough guys appeared as male ingenues and is possibly the first actor to have bounded onstage to say, ?Tennis, anyone??

Still in tennis whites but with some darkness starting to seep through?

Bogart appeared in 11 films between 1930 and 1936, including Pre-Code staple?Three on a Match, as a really skeezy bad guy, but Bogart?s film career was going nowhere until Leslie Howard insisted that Bogart repeat his sensational performance as Duke Mantee for the 1936 film version of?The Petrified Forest.

Playing Mantee in the Broadway production had been a breakthrough for Bogart, who was trapped in two kinds of typecasting, playing upper-class twits onstage and cheap crooks in movies. Veteran Broadway producer Arthur Hopkins had seen ?Bogart?s performance in a play,?Invitation to a Murder,and caught something everyone else had missed: Bogart?s deep melancholy. Hopkins knew Bogart was the actor to play Duke Mantee, a weary gangster, a psychopath who sees his time running out but will not give himself up. Mantee?s look, the stubble and close-cropped dark hair, are an obvious nod to John Dillinger, who was still in the headlines when the play opened. Bogart threw himself into the role as if his career depended on it, and it probably did. The critics were astonished?they had no idea Bogart had it in him.

Bogart and his benefactor Leslie Howard in The Petrified Forest (1936). Bogart named his daughter Leslie Howard in honor of the actor who was killed during World War II.

But when it came time to make the movie, Warner Bros decided to go with Edward G. Robinson, and Bogart was understandably angry and disappointed. (Editor?s note: Another difference in Bogart and Huston was their relationship with Jack Warner, whom Bogart, like so many actors, loathed and Huston mostly liked.) Then two things happened: Robinson walked out on Warners, and Leslie Howard, who had starred in the stage production of?Petrified Forest?and was to repeat the role in the movie, went to bat for Bogart. Howard was a huge star at the time, and when his agent cabled?Warners no Bogart, no Howard?Bogart got the part. The critics raved, but Warners takeaway was simply that he was worth more money. They had no intention of giving him better parts.

Bogart?s Duke Mantee seems like he can hardly bear the pain of being in his own skin.

I can?t find any reference to Bogart and Huston knowing each other in New York, but it?s quite possible that they did. Both ran in theater circles, and both liked to drink and tell stories into the wee hours. They would have had many mutual friends and probably hung out at the same watering holes. Even if they didn?t, though, Huston would have known Bogart from his movie appearances, and certainly would have been aware of his work in his mentor Wyler?s?Dead End?(1937), as Baby Face Martin, another hood?but Baby Face had a little of Mantee?s melancholy. Perhaps Wyler?s direction brought that out.

After?Petrified Forest, Warners made Bogart a leading man, but strictly in B pictures. In 1939 we see him as Bette Davis?s Irish horse trainer in?Dark Victory,?attempting a brogue, which is just painful. He?s not bad in a rather dull part but that brogue?not all good actors do accents well. Stanwyck?s rare attempt at an accent in?The Lady Eve?is ridiculous, and somebody had enough sense to let Gable speak naturally in?GWTW, though he?s supposed to be from Charleston. In?They Drive by Night?Bogart has a weak supporting part and not much screen time to George Raft?s lead. And worst of all, in?The Return of Dr. X, he played the title role, a zombie with a pet rabbit. That role had been turned down by Bela Lugosi.

Doing his Susan Sontag impression in The Return of Dr. X (1939)

John Huston had done well by Warners in the late ?30s, and after contributing to the ?script for?Jezebel?(for Wyler),?Sergeant York?for Howard Hawks, and?High Sierra?for Raoul Walsh, he knew the time was right to press his advantage and get the studio to let him direct. So his new contract included a clause stipulating that, and Warners agreed. Huston had chosen?The Maltese Falcon?for his directorial debut. Warners had already filmed it twice, in 1931 and again 1936, that time as?Satan Met?a Lady, starring Bette Davis and Warren William, and they still owned the rights, so it wouldn?t cost much.

Director Jean Negulesco wrote in his memoir that he had spent months preparing a new adaptation of?The Maltese Falcon?when he was informed Huston was to make it. Huston had had his secretary do the standard thing, go through the book and divide it into scenes and shots from which he would develop his screenplay. He planned to stick very closely to the book. About a week later he was astonished when?Jack Warner?s office called: Somehow Warner had ended up with the secretary?s coverage, read it, and was?authorizing Huston to start filming in two weeks.

Raft beginning to realize he had outsmarted himself and handed Bogart two career-making roles

Bogart?s greatest and totally unwitting champion was George Raft, who turned down several of what would become signature Bogart roles. Walsh had wanted Raft badly for High Sierra, but Raft nixed it. And Raft came through again on Maltese Falcon, turning down the role of Sam Spade. Huston was thrilled: He had wanted Bogart anyway.

Sam Spade was the perfect breakout role for Bogart, the part that gave him a star look and persona. Perhaps Bogart?s stardom had been waiting for the ?40s, for wide-lapeled trench coats and fedoras to come into style, and for his persona of heroism concealed in world weariness and cynicism. In Huston?s adaptation Spade?s cool cynicism is a cover for his moral compass, which wasn?t so true it had kept him from having an affair with his partner?s wife.

Across the Pacific (1942): Huston with Bogart and Astor

Production went smoothly. Huston, Bogart, Lorre and Astor became a regular gang at the Lakeside Golf Club, across the street from the studio, where they ate and drank and hung out after finishing up for the day. Huston had convinced Sydney Greenstreet to make his first movie, at the age of 61, and all of them swung into action when visitors showed up on the set: Bogart would start haranguing Greenstreet, and Lorre and Astor would rush into her trailer so that Lorre could make sure the visitors could see him let himself out, zipping his fly. They had a wonderful time, they finished on time and within budget, and the movie was, to Warners? great surprise, a huge hit.

Huston?s career as a director was launched with a bang, and Bogart was, finally, a movie star.

You can see in the posters that Warners didn?t at first know what they had: Bogart looks a lot like High Sierra?s Roy Earle (but perhaps the posters were done before seeing Maltese Falcon, so the illustrators didn?t know what Spade looked like).

Sam Spade looks a lot like Roy Earle in this poster, which was probably done without seeing any stills from the movie

Huston and Bogart next worked together on a?Falcon?follow-up,?Across the Pacific, which united all of?Falcon?s?principals except Lorre, who was otherwise engaged. It?s not in?Falcon?s?league, but Bogart?s and Astor?s playful romantic repartee is delicious, and the heavy-handed espionage plot, with Greenstreet a Japanese master spy and about as many inscrutable and/or murderous Asians as a single movie could cram in probably seemed less silly in the wake of Pearl Harbor. Just before shooting was completed, Huston?s military orders arrived and filming was completed by Vincent Sherman.

Huston spent the next couple of years making films for Frank Capra?s unit in the Signal Corps. When the war ended he had, as so many other did, difficulties with reentry, reportedly spending a number of nights armed, in Central Park, hoping for an altercation he could shoot his way out of. Bogart spent most of the war years making war/propaganda movies (Action in the North Atlantic, Thank Your Lucky Stars,?and?Sahara?in 1943;?Passage to Marseilles?and?To Have and Have Not?in 1944) then from 1945 to 1948 appeared mostly in crime/noir:?Conflict?(1945);?The Big Sleep?(1946);?Dead Reckoning, The Two Mrs. Carrolls, and?Dark Passage?(1947).

John went home with two Oscars (Best Screenplay, Best Director) and Walter took home a third for Best Supporting Actor at the 1948 Academy Awards

Their next huge collaboration came that same year with?Treasure of the Sierra Madre?(released January 1, 1948). Huston writes a lot more about B. Traven, the mysterious author of the novel, than he does about Bogart and making the film. Other sources point out that?Treasure?was one of the first Hollywood movies to be shot entirely on location, and that Huston was determined to capture the story?s unforgiving terrain, not to make a standard studio movie with Southern California standing in for the Mexican desert.

Bogart, Huston, and Tim Holt form the unstable trio of Treasure

Unlike Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Cary Grant or a number of other top stars who were careful not to play roles that would alienate their fans, Bogart continued to play bad guys when he got the chance, as long as the roles were interesting and presented him with a real acting challenge.?Treasure?proved?his biggest challenge yet. Fred Dobbs doesn?t start out malevolent. In the film?s early scenes he is an affable enough guy, down on his luck but reasonably congenial, with only the first hints of what he is to become. But as?he and his colleagues close in on realizing?their dreams of wealth, cracks in his personality appear, then widen. Paranoia and aggression erode his character; his eyes are taken over by fear and the exhaustion of constant calculation?where does the next danger lie? Who needs to be eliminated next?

Huston had wanted to make the movie for years but couldn?t get a studio behind him. Once Bogart and Walter Huston were on board, though, Warners approved?and production moved forward. Jack Warner did a 180 when he saw the finished film, proclaiming?Treasure?the best movie the studio had ever made (it?s colossal, it?s stupendous!).

Bogart, Huston & Huston

Huston?s adaptation was structured so that Fred Dobbs?s descent into murder and madness was counterbalanced by Walter Huston?s extraordinary portrayal of Howard, the grizzled but unbowed old prospector whose joie de vivre keeps the film ?on track. Walter Huston won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. John won Best Director and Best Screenplay Oscars?a stunning night for the Hustons.

Huston and Bogart would together make one more movie that was central to both their careers. It was also central to Katharine Hepburn?s career.

Like Huston, Bogart, and almost everyone else in Hollywood, Hepburn had her own problems with the red scare. Hepburn was the proud daughter of a progressive feminist, and she had set the country on fire with speculation about her political sympathies when she delivered a stemwinder of a speech for Henry Wallace, who was the Progressive Party?s 1948 nominee for president. Hepburn appeared not in her trademark slacks but in a dress? a?red?dress, no less?and her speech was no less inflammatory. Newspapers all over the country ran the story, and though Hepburn kept her mouth shut and waited for the furor to die, it didn?t. Why she was never called to testify by HUAC is not entirely clear, but there is speculation that Tracy and her rabid anti-communist costar Adolphe Menjou put in a word for her.

I love how posters, shall we say, creatively depict the movie?s stars?check out the Titian-haired sexpot who?s supposed to be spinster/missionary Hepburn!

In any case, when Hepburn saw the script for?The African Queen, she recognized it for what it was?a way to clear herself once and for all of any suspicions she was anything but a loyal American, even a patriot. Here?s a movie where Bogart and Hepburn torpedo a German boat?put that in your pipe and smoke it, Joe McCarthy!

The African Queen was a critical and box office smash, and it brought Bogart his only Academy Award.

At home with Oscar

While Huston had been interested in making the film for years, the timing benefited him and Bogart as well. While Bogart had changed his mind and published a?Photoplay?piece, ?I?m No Communist!,? Huston?s convictions were unchanged, and in 1952 he moved to Ireland to escape the poisonous political climate in America. He always felt Bogart should have held his ground. But Bogart saw it differently. He was under the very real threat of blacklisting, with a young wife to support, and he had Bacall?s career to consider as well. Huston didn?t hold it against Bogart, though others did, and their friendship survived the issue and lasted until Bogart?s death from esophageal cancer on January 14, 1957.

The collaboration had produced one more film,?Beat the Devil?(1954), that was a flop at the time but?has slowly gained a cult following. The three films central to their careers are still considered among the best not just from Huston and Bogart, but ever made in Hollywood.

Huston spoke movingly of visiting Bogart in his last days, drinking and telling stories, and he delivered a fine eulogy at Bogart?s memorial service:

?Himself, he never took too seriously?his work most seriously. He regarded the somewhat gaudy figure of Bogart, the star, with an amused cynicism; Bogart, the actor, he held in deep respect?. In each of the fountains at Versailles there is a pike?which keeps all the pike active; otherwise, they would grow overfat and die. Bogie took rare delight in performing the same duty in the fountains of Hollywood. Yet his victims seldom bore him any malice, and when they did, not for long. His shafts were fashioned only to stick into the outer layer of complacency, and not to penetrate through to the regions of the spirit where real injuries are done. He was endowed with the greatest gift a man can have: talent. The whole world came to recognize it?. We have no reason to feel sorry for him?only for ourselves for having lost him. He is quite irreplaceable.?

The same can be said of Huston and the work the two left us.

This post was written for the Symbiotic Collaborations blogathon, hosted by Theresa at?Cinemaven on the Couch. Head on over and check out the other entries?there are some humdingers!

Recent Comments