Where all parents are strong and wise and capable, and all children are happy and beloved?

?H.I.,?Raising Arizona

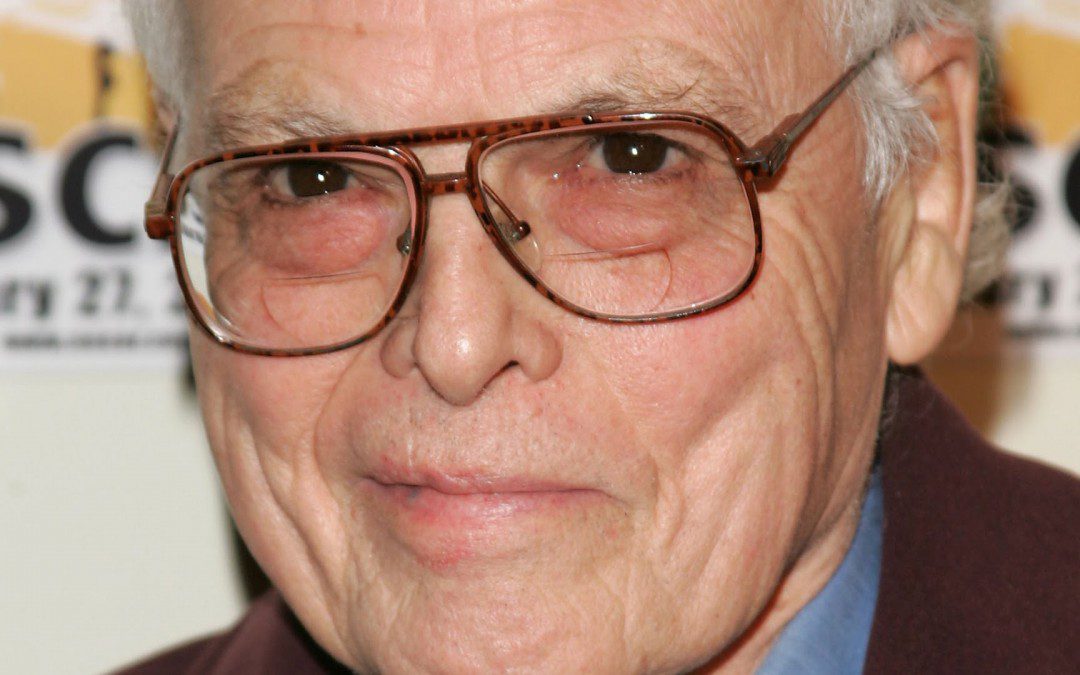

It?s an intense little face. The Cupid?s Bow mouth and tiny, turned-up nose sit beneath large, dark, deeply?serious eyes. Dickie wasn?t just cute, he was beautiful?I think the most beautiful of the great child actors of his day. Of the others, Mickey Rooney, Freddie Bartholomew, Bobs Watson, none were flat-out gorgeous. Jackie Coogan in the ?20s and Roddy McDowell in the early ?40s were stunning. But in his era, Dickie?s looks were so incredible that the kids who competed with him for roles and some who came after were compared to him?as the ideal of boy beauty. Dean Stockwell, who started working in the early ?40s, was constantly compared to Dickie (though Dickie had by this time aged out of his little-boy?beauty), and Stockwell?hated?it.

Then there was the voice. If the features were shockingly sweet, the voice was a bit gruff, which kept Dickie from being too precious?which he wasn?t. Dickie was a regular kid in?gesture and?attitude. Of course he mugs sometimes (how could he not?), but his natural quality coupled with his looks made him very popular with directors in his heyday.

Dickie was ?discovered? by Joseph Selznick?s secretary, who was picking up Dickie?s mom for work. He got the gig and appeared onscreen for the first time?at the age of 18 months in the 1927 silent release?The Beloved Rogue,?playing baby John Barrymore. By the time he was 10, in 1935, he had appeared in close to 60 movies.

To moviegoers, particularly in the early 1930s, Dickie Moore was royalty. He was in the top tier of child movie actors, appearing in scores?of movies with costars like Barbara Stanwyck, Marlene Dietrich, Walter Huston, and Spencer Tracy, directed by the likes of William Wellman, Josef von Sternberg, Frank Borzage, and Cecil B. DeMille. He was the leader of the Little Rascals, as Jackie Cooper had been before him. He signed autographs by the thousands (?Your friend, Dickie Moore?) and lent his name and image to a children?s clothing line and other merchandising endeavors. How many mothers dreamed of the same for their children? And how many kids dreamed of being Shirley or Jane Withers or Margaret O?Brien or Mickey Rooney or Jackie Cooper?or Dickie Moore?

Dickie?was part of my favorite Little Rascals lineup, leading the gang with little Spanky McFarland and his real-life best friend Stymie Beard in eight shorts released between August 1932 and May of ?33. But just two years later, at the age of 10, Dickie was painfully aware that he was slipping. A near-fatal bout of scarlet fever (which, due to an inept family doctor, almost cost him his hearing) kept him sidelined for almos a year, and when he was ready to come back, things had moved on without him. The parts got harder to get, fewer and farther between. Still, he got the occasional prestige movie and worked with first-rate directors. In the early ?40s he had a featured role as?Gary Cooper?s brother, George, in Howard Hawks?s?Sergeant York,?and also a nice couple of scenes as 15-year-old?Don Ameche in Ernst Lubitsch?s?Heaven Can Wait. He famously gave Shirley Temple her first screen kiss in?Miss Annie Rooney?(1942), and he had an important if?silent role opposite?Robert Mitchum?in Jacques Tourneur?s?Out of the Past?(1947).

Birthday Blues?(1932): Mixing the prize cake. Dickie?s trying to raise $1.98 to buy his mom a birthday gift by selling pieces of a prize cake, 10 cents a piece.

Still, like most child stars, he was unable to bridge from his early success into a successful career as an adult actor. He was in good company?Shirley Temple retired from the screen at 20, and after World War II Mickey Rooney found it tough going to chart?a path out of his emblematic role as Andy Hardy. Dickie?s?last appearance in a first-class?movie was a brief scene in?The Member of the Wedding(1952), playing much rougher than I think of him as a lonely soldier who makes a brutal pass at Julie Harris in the back room of a bar. Dickie was 27 at the time and was struggling to navigate the world outside the movie business and to figure out who he was apart from his role as movie actor and family breadwinner. He had performed in close to 80 films?impressive for a lifelong CV, but astonishing for a man not yet 30.

Out of the Past (1947): As the Kid, who can?t hear or speak, Dickie had a small but central role in this essential noir.

Starting in early adolescence, Dickie consulted a series of acting coaches and asked, ?Should I quit?? hoping for a Yes. But they all said it would be a shame not to develop his talent. Dickie figured out as the other child stars did that the instinctive acting that had made them stars wasn?t going to keep them working now that they weren?t insanely beautiful tykes. He had been working since he could walk, and now he would have to do the long, hard work of learning to act. But he didn?t put all his eggs in one basket: Starting in high school, Dickie worked on writing and producing, learning other aspects of the business behind the camera. And though it was a bumpy road he eventually established himself in New York as an actors? publicist, an insider with his own booth at Sardi?s. His personal life wasn?t smooth either?like a lot of us and like so many of his fellow ex-child stars, he struggled with substance abuse, broken marriages, depression, a suicide attempt, and years of psychotherapy (seems like most of the interviewees in Dickie?s book spent many a year on the analyst?s couch). But he stuck with it and eventually found happiness and stability in his late-life marriage to actress-singer and ex-MGM star Jane Powell, who was left widowed when Dickie passed away from natural causes this past September just five days shy of his 90th birthday.

My grandfather used to say that if you cut a notch in a stripling, it would still be there when the tree was 500 years old. Looking at Dickie as an older man I can still see that impish, cherubic?7-year-old, along with the man he has become. And the notch that his upside-down childhood cut in Dickie never went away, but he learned how to work with it. That?s one of the advantages of living for a while: You get to learn to live with yourself.

Growing Up Is Hard to Do

Many years ago I had an epiphany:?Everybody?loses their childhood. If it was lousy, you feel like you?never had one, and if it was great adult life is disappointing because the world so much harsher?than your early experience. The former may be too wounded to make good lives (though the resilient pull through), and the latter may always be plagued by?the vague dissatisfaction of those who peaked too early. Maybe that?s part of what?s so compelling about child stars: We get to see them as we almost never get to see ourselves, as beautiful babies, then sometimes we actually get to watch them not only grow our of that but beyond it, from gods to mortals. Whether they crash and burn or survive and thrive, we get to witness their unfolding in ways we can?t observe our own.

1934: One of those staged photos. It would be eight years before Dickie and Shirley would make?Miss Annie Rooney.?Its claim to fame was that?Dickie gave Shirley her first screen kiss. It was Dickie?s first kiss, period.

1934: One of those staged photos. It would be eight years before Dickie and Shirley would make?Miss Annie Rooney.?Its claim to fame was that?Dickie gave Shirley her first screen kiss. It was Dickie?s first kiss, period.

Publicity shot from Miss Annie Rooney (1942), a sweet little movie. Dickie is wonderful in it, though he suffered agonies in its making.

Adults and even older kids dream of stardom and make huge tradeoffs to get it, but the kids who entered the movies as babies or toddlers were working before they knew how to read or write, before they could possibly understand their lives or the industry.?The realities of being a child star are the same as those of being an adult star, except that the kids don?t have any choice and they?don?t understand a lot of what?s going on, why their?lives are?the way they are.

The tiny group of kids who represented childhood for moviegoers the world over, who were idealized and adored and envied, had a distorted and limited experience of their own childhood. When Dickie interviewed Shirley Temple for his fascinating 1984 book?Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star (but don?t have sex or take the car), she told him that when she was little she had assumed that all children worked. And how they worked: Up at 6 to get to the studio by 8, up earlier if shooting on location. Three hours a day in a classroom with a teacher doing her best to actually teach you something while both of you were under constant pressure to get you back on the set?waiting costs money, and you were making everybody wait. Learning your lines at night before bed. And all over again the next day, and the next?if you were working. If you were a freelancer like Dickie, not working meant some time at public school, which gave?him a chance to observe normal kids even if he didn?t feel like one. But it also meant tremendous financial pressure, knowing his?family was barely getting by, that it was up to him?to keep food on the table.

Dickie says that he was never aware of the larger business of moviemaking, he was fully preoccupied with his immediate situation?trying to please his parents, his director and fellow actors. That?s something most of the former child stars Dickie interviewed had in common, they had been trained to please other people, and learning to think and act on their own behalf remained a lifelong challenge. But he noticed other things?that indicated?his precarious position. He?could tell how the studio felt about him?by where he?had to park. If he?wasn?t doing so hot he?would have to park near the front gate and take a shuttle to where he was working. If he?was doing better he?d be allowed to drive all the way to the soundstage. And lunch: On location, the elect got the good box lunches, with chicken. When the chicken was gone, he knew he was in trouble.

Just like adult actors, child actors have to learn the technical aspects?of performing before the camera, how to hit their marks, hold their heads to catch the light, know their own and everybody else?s lines, and repeat the scene until the director is satisfied. Plenty of?adults can?t master that aspect of the work, doing all that stuff while speaking and behaving naturally. That these very young children were able to do so is in itself remarkable and bizarre. That some of them could also act with the authority and conviction of their most illustrious elders is weirder still.

And the acting was only one part of it: So many child actors were their family?s sole support, especially but not only during the Depression. They were barely schooled and few?learned skills that would help them adjust when their great days on the screen were over. Very few of them ended up with any of their often?vast earnings, and those who did rarely had the skills to manage their money. They were socially isolated?kids in the neighborhood knew they weren?t normal, so that social avenue was frequently?closed, and the acting kids were generally isolated from each other because they were always working and because of professional rivalries (between their parents). Fifty years after Shirley?s mother slighted Jane Withers after?Jane was such a hit in?Bright Eyes?(1934), her one movie with Shirley, Jane was still obviously hurt at how Mrs. Temple had ostracized her.

As you get older you look back over that increasing distance between yourself as you are and the child you were, and see yourself with increasing?clarity and?detachment. A lot of things you might have believed?about yourself, projections from relatives who didn?t like you for example, begin to wither as you are finally able to see yourself as the cute little kid you really were. Dick Moore was in his late 40s when he decided to track down his ex-colleagues, to try to figure out what had happened to him and to them, why life was so upside-down. He spent the next few years interviewing them, and connecting with other ex-stars and thinking through his own experience in writing was cathartic.

Playing a young man with a healthy libido seems to?have come naturally to Dickie.

Gabriel Over the White House?(1933): Treasure hunt in the president?s office (which does not seem to be the Oval Office)

One way in which child stars are no different from their elders is that both rely on personality and charisma. Acting is something you do; in the movies there?s also what you?are?how that mysteriously communicates through the camera and onto the screen. Sometimes what people project is completely at odds with who they actually are. Warren William, for example, the Pre-Code king of sleazy tycoons, was in real life a rather shy, soft-spoken fellow, nothing at all like the cruel, ferocious bosses he often played.

In Dickie?s case, though, I think the camera found something very real in him. As he got older he became self-conscious and couldn?t always recapture that quality. But when he lucked out and got to work with a sympathetic director, as in?Sergeant York?and?Heaven Can Wait, teenaged Dickie did just fine. When they gave him room to connect with himself he brought his own inner stillness and the acting skills he was acquiring, and the results were impressive. In Sergeant York, Miss Annie Rooney, and Heaven Can Wait, Dickie is on his way to being a real actor. The first of his films where I see this happening is a Warner Bros. programmer called My Bill, from 1938, when Dickie was 12 or 13.

My Bill?is an unremarkable movie at first glance. But this little soaper, headlined by Kay Francis and costarring Dickie and Bobby Jordan, Bonita Granville, and Anita Louise, is worth a second look. It catches both Dickie and Francis on the way down. Francis had lost her place as the queen at Warner Bros., and while she was still topping the bill, it was in movies like this: low-budget, hastily scripted. With more money and more time, the script might not have had so many worn spots, the characters might have been better developed. Kay Francis?s character in particular suffers from the lack of development. We?re supposed to find her sympathetic but as written, her denial of the family?s dire financial situation seems tone-deaf and clueless, not to mention counterproductive. And her three rotten?kids?Bill is her fourth child, the youngest?could also use beefing up both as individuals and in their relationships to each other. The whole thing has a rather rushed feeling about it, and no wonder. Tight budget, tight schedule.

But?My Bill?is better than many similar starved movies, left to grow as best they could in rocky soil with little light. One thing in its favor is that it?was directed by a pro, John Farrow, whose later credits include several notable noirs:?The Big Clock?(1948),?Where Danger Lives?(1950), and?His Kind of Woman(1951). Farrow manages to generate some actual drama by skillfully developing Dickie?s two pivotal relationships, with his mother (Bill calls her Sweetheart) and the rich, lonely old lady down the street whom he befriends. That provides the story with enough connective tissue for the movie to reach a rather satisfying conclusion, even if the narrative is pretty thin. The production values are fine?the sets don?t have that bleak, threadbare look of so many Bs, and there?s a decent musical soundtrack (as opposed?to that particular lonely silence that suffocates really neglected movies).

The denouement, as it is so often in Bs, tries to resolve?everything in a five-minute scene and a couple of monologues that were barely set up in the rest of the movie. It?s just thin. But it is emotionally satisfying to see the evil aunt shoved out the door and the wayward kids back in the fold, all due to good old Bill. Had this movie been given a little more encouragement, it might have been a more than what it is: a programmer with modest pleasures. And even as is, to Warners? surprise,?My Bill?got good reviews and did all right at the box office.

Dickie writes how frustrated?Francis was at her situation. And he had his own problems: Before his illness the jobs had just come, he had been sought after. Now he had to meet with directors and sometimes even casting directors, just like everybody else. Worse, because he had been at the very pinnacle, and the only place to go was down.

In?My Bill,?Dickie was 12, he same age as Shirley when her studio dumped her.. He?s still a looker (he always was), but he can?t wow an audience just by being onscreen. Bill is a great part for Dickie because like him Bill is a pretty normal boy, if a bit mature and a lot kinder than the average kid. Dickie was not particularly artistic?he didn?t come from a performing family like so many other kid actors did. He liked to poke around in ponds and collect bugs and polliwogs in jars, and Bill lets Dickie work from that part of himself.

Bill?s angry scene, when he tells off his evil aunt, isn?t terrible, but it?s just competent. Mickey or Freddie or Jackie Cooper could have summoned the furies. But Dickie brings a sympathetic quality to his scenes with Kay Francis that is lovely. The way he listens when Sweetheart?explains that the old lady she and Bill have befriended (Bill calls her ?Duchess?) is dying. His short scene with the Duchess is a beaut?he really pulls it across, and it?s tough stuff. He has to have a game face for his friend but show us he?s struggling to keep it together. He has to be solid?but really sad, to hold his ground and not fall apart or run away. It?s not a scene he could have handled a few years before, by mimicking his mother?s line readings, it requires real acting. And it works partly because we believe Dickie and partly because one of the only things the script has accomplished is showing us that Bill is that kind of kid. But it takes Dickie to bring it to life.

Dickie said crying scenes were the worst. They were the standard, the big test for child actors. Some could do it on command. Most required intervention from a parent or director. And if the kid couldn?t make with the waterworks after a few takes, out came the glycerin?drops, which meant you couldn?t do the job on your own. Bobs Watson was one of the champion cryers?if you haven?t seen?On Borrowed Time?or?Boys Town,?go do so. Ann Rutherford told of being on set with Bobs one morning when he was supposed to cry, but Bobs didn?t feel like crying that day, he was in a fine mood. The director was losing his patience. Bobs?s dad, Coy Watson, who always accompanied him at work, pulled Bobs aside, showed him a stop watch, and Bobs looked terrified, raced back onto the set, and delivered a hair-raising performance. When it was over he looked at his dad, who nodded that?all was well. Rutherford said Coy had told Bobs that if he didn?t get the scene done within 10 minutes his dog would have to be sent to the pound.

Like Shirley and many other child actors, Dickie?s mom taught him his lines every night. They would go over his lines first, then she would read the other parts and cue him. When she read him his lines, she gave them what she thought were appropriate dramatic readings, and Dickie just tried to do what she had done. Her instincts must have been pretty good. But while a gift for mimicry is useful for an actor, it?s like playing the piano by ear?it will only get you so far.

Dickie was not without ability?he was far from just a pretty boy, as is evident in both?My Bill?and another film from a period of transition, in this case when he was a teenager, Howard Hawks?s?Sergeant York?(1941). Dickie gets a fair amount of screen time (though not a lot of dialogue) in the supporting role of George, Gary Cooper?s younger brother.?Sergeant York?was perhaps Dickie?s favorite of his films. Hawks put him at ease, telling him he didn?t need to smile anytime in the whole movie if he didn?t feel like it, releasing Dickie self-consciousness so that he felt free to smile when it was natural. Also, Dickie adored Gary Cooper, whom he treasured as a father figure. Dickie asked Cooper what kind of gun he should buy, and Cooper thought carefully before answering, recommending an affordable gun Dickie used for 20 years. He also taught Dickie how to throw a knife.

You can see in the movie how Dickie feels about Cooper, not from anything overt, but from the believability of their relationship, from how devoted Dickie is. One of the weak points in?My Bill?is that Dickie doesn?t seem to have any relationship to his three siblings?you have no sense that these four kids are really related. But the way Dickie watches Cooper competing in a shooting contest? his faith in him and desire for him to win is all over?Dickie?s face.

Dick Moore?was one of the very last living actors whose work reached back to the silent era. Dick Moore left us an incredible body of work onscreen, but I think that, like his costar Shirley Temple, his most impressive legacy is that he not only survived his peculiar life, he came to terms with it and with himself. His film work offers many pleasures, but what he did with his life is downright inspiring.

This entry was written for the 4th annual What a Character! blogathon, hosted by Aurora, Paula, and Kellee at?Once Upon a Screen,?Paula?s Cinema Club, and?Outspoken and Freckled. Lots of great entries, go check ?em out!

Recent Comments